Advertisement

High Anxiety: How I (Sort Of) Overcame My Fear Of Flying

Imagine this tense scene at Logan International Airport's Terminal E earlier this summer:

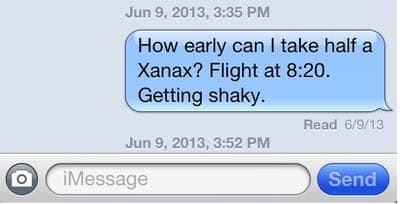

A woman with two young children rummages through her medication bag while awaiting an overnight flight to Europe. She pulls out a bottle of pills, then grabs her phone to text her therapist:

Woman: How early can I take half a Xanax? Flight at 8:20. Getting shaky.

Therapist's response: You can take it now. You can do this!!!!

The scene, sadly, is all too real; that frantic woman is me.

I hate flying. Just writing the word 'flying' gives me a pang of dread, twinges of imminent diarrhea and the feeling that I might choke on my own fear.

I'm like Woody Allen on the plane in "To Rome With Love," a death-grip on Judy Davis' arm when turbulence hits. "I can't unclench when there's turbulence," he says. "I don't like this, the plane is bumpy, it's bumpy... I don't like when the plane does that... I get a bad feeling."

In my case, to avoid this excruciating feeling, I have cancelled family trips at the last minute, pretended to be ill, and dragged my children on a 30-hour train ride from Boston to Orlando.

This summer, I'd finally had enough of my fear and its invasive grip on my life. But could I overcome it? I honestly wasn't sure.

(Before I go on, let me say clearly that mine is definitely a "first-world problem." There's no poverty, abuse or major life-threatening illness going on here — just a "problem bred of privilege," as one friend put it. Still, it's fairly widespread, and worse since 9/11. Though precise prevalence numbers don't exist, a 2008 study published in the Journal of Anxiety Disorders says fear of flying is "estimated to affect 25 million adults in the United States and nearly 10–40% of the adults in industrialized countries." Similarly, a 2007 New York Times report quotes an NIH estimate that about 6.5 percent of Americans fear flying so intensely that it qualifies as a phobia or anxiety disorder.)

Russian Planes With Duct Tape

It wasn't always this way for me. As a single, childless reporter, I flew all over: to Africa and Vietnam, to Cuba on a Russian-made plane lined with duct tape and in China on a domestic flight on which the pilot told everyone to move to the left side of the plane for "balance." I flew in tiny, private planes across Washington state in bad weather, and to Provincetown on a little 9-seater.

Then, while walking to work across the Brooklyn Bridge on September 11, 2001, I saw the second plane hit the World Trade Center. A year later, when I was pregnant with my first child, my flying anxiety suddenly took hold. When the baby was six months old, I rescheduled a family trip abroad to avoid heavy rain. After that, for the next 10 years, I never took a flight more than three hours long.

I said "no" to weddings, work trips and excursions with my husband to romantic locales. I always had a good excuse not to travel, but in reality, avoiding these trips was all about my fear.

Flying Coffins And Familial Anxiety

There are likely genetics at play here: anxiety is a family trait, and several of us have suffered with flying fears. Years ago, a close relative freaked out on a flight from D.C. to San Francisco and, after a scheduled layover in the midwest, refused to get back on the plane. Instead, he took a train home. For a while, my father called planes "flying coffins," and took a heavy dose of Klonapin, usually prescribed for seizures and panic attacks, before flights.

I didn't want to be that person: gripped by fear, unadventurous and cooped up in my own little bubble. Moreover, I didn't want my children to see me that way. So I tried to change. I met with one therapist who had me close my eyes and, in a kind of hypnotic state, imagine bad turbulence while articulating my physiological responses: heartbeat speeding up, nausea rising. Still, I knew I was on the ground.

Another doctor gave me fact sheets about airline safety and urged me to focus on the rational side of things. When it comes to safety, she'd say, taking my kids on a plane is far safer than driving them to school, which I do every day without a care.

Still, the ability to rattle off facts about flight safety, and the astonishing record of no fatalities (until recently) on U.S. carriers for the past decade, never worked for me. Emotion trumped rationality every time. In my gut, I felt a direct link between getting on the plane and feeling trapped, out of control. I envisioned a fiery, harrowing death and I imagined what I'd say to my kids as we went down. "I love you, I'm sorry, I wish I could protect you."

As the former journalist and risk assessment expert David Ropeik wrote in a recent piece on people's fear of cancer: "The way we assess risk relies more on instinct than intellect. What matters most are not the facts, but how those facts feel. That leads us to worry about some things more than the evidence suggests we need to, and vice versa."

Like an addict desperate for a fix, I'd log on to Boston.com and click the extended forecast, my pulse racing.

I have managed a few short flights over the years, but always, in the days running up to departure, I'd check the weather obsessively: five, six, seven times a day. Like an addict desperate for a fix, I'd log on to Boston.com and click the extended forecast, my pulse racing. My mood would rise or fall based on the little sunshine icon, and whether it was clear or eclipsed by a dark cloud.

The day before a short flight to Richmond, VA for a family celebration, my heart sank when I saw a big storm predicted; I called Jet Blue and had a long discussion with a supervisor about the weather. I emailed friends and let my anxiety spew forth; I asked my husband if it would be okay to change the flight by a day. "No," he said. The tension between us escalated. Finally, I prevailed and booked us on an overnight train. It was a painful 10-hour ride to Richmond, sitting up all night, with no quiet car and constant stops and dings and conductor announcements. Last year, when I arranged for us to take the 30-hour train to Orlando, we got a sleeper car. (And met many other passengers doomed to the same cramped quarters due their own flying phobias.)

The Final Straw

I meditated and popped anti-anxiety pills but what really helped was exercise. On a flight home from Puerto Rico, with snow predicted in Boston upon our arrival, the only thing that got me on the plane was a long, hard run on the beach before we boarded. Indeed, the single most consistently reliable treatment for my anxiety through the years has been daily physical exercise: running, swimming, yoga, the treadmill, whatever. It doesn't have to be much, it just has to happen. So does good, solid sleep and nourishing food.

So there I was, managing, but mostly trying to squelch my anxiety, while avoiding flying as much as I could.

Then, earlier this year, my kids and I had the chance to go to Greece with a bunch of families from their school. The trip sounded dreamy — Crete, Delphi, Hydra, Athens — and I really wanted to do it. But I knew I couldn't manage alone.

So I found a new therapist, Luana Marques, Ph.D, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor at Harvard Medical School who works at Massachusetts General Hospital's Center for Anxiety and Stress Disorders. She's just written a new book, "Almost Anxious," for people who don't necessarily meet the text-book criteria for a full-blown anxiety disorder but nevertheless have debilitating symptoms. In other words, me.

Dr. Marques specializes in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which is based on the idea that a person's thoughts — rather than external events — cause certain feelings and behaviors. CBT essentially helps you identify the "distorted, irrational thoughts" that are often associated with negative emotions, and figure out new ways to think about fraught situations. Exposure to anxiety-provoking situations is also central to this type of treatment.

'It will be hard,' she said. 'But I think you can do it.'

After we talked in detail about my history, Marques determined that while I obviously have a fear of flying, it's probably part of a broader condition, Generalized Anxiety Disorder. We concluded that the only reason I wasn't taking the trip was my own anxiety, and that I should just book the flight and work on making it happen. "It will be hard," she said. "But I think you can do it."

Two asides:

• Marques, who is not an M.D., urged me to consult with my primary care doctor regarding medications for my anxiety, which I did. Any references here to taking prescription drugs were done after much back and forth with my internist.

• Obviously, Marques had full permission from her patient — me — to discuss my case.

So, I did everything possible to postpone making a decision about the trip: I waited until the last minute, and then beyond, to make reservations. Giving my credit card number to the travel agent sent me into a panic; I immediately regretted what I'd done. My anxiety spiked. I woke up in the night dreaming of cancelling. I began the pattern of driving my husband crazy with my worrying. 'Will it be okay if I simply can't manage this and have to cancel?' I'd ask, imploring him to support me despite my irrational behavior. Actually, no, he said.

My Catastrophizing

Meanwhile, Marques and I kept meeting. It became clear that throughout my life, I've had major anxiety but managed to bury my feelings temporarily and continue to function, as a professional, a wife, a mother. Of course, everyone has stress and worries, so what's so special about my anxiety? Well, I scored pretty high on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire that Marques gave me to fill out. I'd begun taking Ativan regularly for my insidious insomnia. And my tendency to catastrophize, and quickly jump to the worst possible conclusion, had intensified. One example:

When my daughter went on a two-night sleepover with a friend in Western Mass., her first, and didn't call to say goodnight as planned, I was worried sick. Around midnight, after no one answered the host's home phone, nor responded to multiple texts or emails, I called the police to check the house. It turned out she was fine, but the house landline was broken.

The day after, a bomb went off at the Boston marathon. This taught me an important lesson: The terrible things you worry about don't happen while other terrible things that you don't worry about do.

Telling A Different Story

During my four or so months of therapy this year, we tried to hold my worries up to the light and diffuse them through rational thinking. I kept a "worry diary" of all of my anxious thoughts, which ran from the petty to the outlandish. ("I won't be able to exercise while traveling with my children," or "These abdominal pains must be the start of an ulcer" or "My child has been in an accident at her sleepover.")

With these thoughts written down, it was fairly easy to identify the distortions. (In psychospeak, was I "mind reading," "negative filtering," or engaging in "emotional reasoning?" Yes, yes and yes.) Then we talked about alternative, more soothing narratives. For instance, "I will be able to make time to exercise while traveling — I always do," and "My child has survived scores of playdates uninjured."

How we frame our thoughts makes all the difference. And that's something we can control.

We tried to replace the negative story lines with more realistic ones. (I've made it through every flight in the past; rain doesn't make flying particularly dangerous.) This, I believe, is key. What I've learned from being in therapy since high school is that how we frame our thoughts makes all the difference. And that's something we can control.

Anxiety Rising

Still, the week before the trip, I was a wreck. Dr. Marques was attending an out-of-town training session and we texted almost daily as I plunged into full-worry mode. Here's a sampling of our texts:

Me: I am getting very anxious re: weather. Don't know how to handle. I'm free after 5. Tnks.

Me (again): Did you get my text yesterday? I'm very anxious and need to talk. Tnks.

Me: Any updates? I'm not great. Thanks.

Her: ...Want to talk Saturday?

Me: Sure. But this is pretty hard to manage.

Her: Do you want to call my covering clinician?

Me: What could they possibly say?

On the day of the flight, my husband, who was not traveling with us, accompanied us to the gate. I kept running to the bathroom while trying to be serene in front of our kids and the two other mothers I was flying with. These are just feelings, I told myself, and they will pass like the weather. I imagined myself as a young child in great need of soothing and kept repeating Bob Marley: 'Every little thing's gonna be alright.'

I kissed my husband goodbye, handed our tickets to the gate agent and looked for our seats as if there was no turmoil raging inside my body.

And, frankly, as soon as the big, newish Lufthansa plane took off, I began to relax a little: it was all out of my hands now. Others around me looked calm; they were laughing and reading. I could do this too, despite my death grip on the armrest.

Indeed, Marques told me that imagining the imminent anxiety is often the toughest part for patients. "Anticipatory anxiety is often worse than actually approaching a fearful situation as it tends to be associated with a great sense of apprehension, catastrophic thinking, and high physiological arousal," she explained via email. "Often, by approaching a situation over and over again, my patients learn that their worst predicted outcome does not happen, which in turn leads to less anxiety in future times when they approach their situation."

The trip, needless to say, was magical: running at sunrise then jumping off the rocks into the turquoise Aegean; the Acropolis lit up after dark; the creamy eggplant and outrageously thick yogurt. But beyond the delicious tastes and mind-blowing history, I experienced a deep sense of accomplishment; the electric rush of 'I'm alive.'

I don't think I'll ever look forward to a flight, but maybe each time it will get a bit easier.

Smooth Air Home

And indeed, after our travels, we calmly boarded the flight home. I thought of taking a pill, but in the end took nothing; just a few calming breaths and the thought of my own bed did the trick. My husband had joined us at Delphi and we were able to fly back over the Atlantic together.

Why had this therapy worked when other efforts failed? Who knows. It was probably a mix of forces: an honest effort by me to truly examine my distorted thinking, a realization that my fears and constant worry were beginning to tear at my marriage and had started to diminish my life. Also, I was highly motivated to take this trip with my girls. But, as Marques said, the mechanism for such changes in thinking are "often unknown."

I do have one lasting flight memory, my anti-Woody Allen moment: As we settled into our seats and each picked our own separate movies, I reclined at the start of Steven Soderburgh's "Side Effects" and took out the lovely salad I'd bought in Zurich. The air was smooth, and with my husband beside me and my children within reach, I looked out the window and thought: Wow, this is pretty nice. Where should we go next?

This program aired on August 2, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.