Advertisement

Why Boston-Area Hospitals Have A Big Range In C-Section Rates

ResumeThough only performed on women, Cesarean sections — the incision in a woman’s abdomen and uterus through which doctors deliver a baby — have become the most common surgery in the U.S.

Many health care experts grimace at this news. Research shows a C-section can have negative consequences for both the mom and the baby. And though childbirth experts have been pushing to reduce C-sections, their sense of urgency has not spread to many doctors or moms, who say C-sections are an important option in the process of delivering a healthy baby.

So are C-sections really that bad? Lots of women have one. It's generally considered low-risk surgery. You can barely see the scars these days. And there’s some dispute about whether they really cost a lot more than a normal vaginal delivery.

So if you're wondering why some people get worked up about rising C-section rates, listen to Dr. Catherine Spong, with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. She says birth is a natural process that prepares a baby to enter the world.

"If you have a Cesarean delivery without any labor, without going through any of those processes, sometimes [babies] have problems with that transition because they haven’t undergone all of those physiologic changes," Spong says.

There’s a growing body of evidence that children born by C-section are more at risk for asthma, type 1 diabetes and obesity. And there are risks for the mom, so preventing first-time births by C-section is particularly important.

"Once you’ve had a Cesarean and you have an incision in the uterus, that incision could open, called uterine rupture," Spong says. "That can be catastrophic for both mom and that subsequent baby."

The odds of that rupture and other bleeding problems are not high, but go up with each birth.

The federal government had hoped to cap Cesarean sections at 15 percent of all births by 2010, but the country blew right past number. In Massachusetts, 23 percent of first-time moms have C-sections. But within the state there’s a big range.

In the Boston area, Cambridge Hospital has the lowest rate of C-sections, at 15 percent, according to data collected by the state Department of Public Health. Tufts Medical Center has the highest rate, with 30 percent, but that's only slightly more than other prestigious teaching hospitals, such as Brigham and Women's and Beth Israel Deaconess.

The gap in rates may have something to do with the culture of these hospitals.

At Cambridge, Tufts Hospitals

The culture of childbirth at Cambridge Hospital begins in a Victorian house, across a driveway from the main hospital lobby. It's the Cambridge Birth Center. Both the hospital and birth center are part of Cambridge Health Alliance.

The center is as close to a homebirth as you can get without staying home. Dr. Kate Harney, the hospital's chief of obstetrics and gynecology, walks up a winding staircase into a room with big windows, painted a soft blue. She sits down on a four-poster bed covered with a diamond-pattern quilt.

The room "has all the emergency equipment," Harney says, but it's "nicely hidden away."

Only about 10 percent of pregnant women who come to Cambridge Hospital give birth in this house. Most women choose a more traditional experience in the main hospital. But Harney says the natural birth focus of the center sets the tone for all hospital deliveries.

"A lot of patients are initially drawn to us here because of our birth center," Harney says, "so that affects how we care for patients in the hospital. We all have to be philosophically and medically ready to take care of women who have this approach to childbirth."

This approach includes:

- An obstetrician, or OB, assigned to the hospital's labor and delivery unit 24 hours a day. OBs at Cambridge Hospital don’t race back and forth between patients in the office and patients in labor, a pressure doctors in many hospitals with high C-section rates face.

- Using family doctors and midwives, who are not trained to do C-sections, to perform almost half the births at Cambridge Hospital.

- Holding off on induced labor until two weeks after a woman's due date. Earlier inductions that don’t progress to full labor are tied to C-sections.

- Using doulas, or birth coaches, to assist in about a quarter of all deliveries.

Harney says doulas are one way the hospital helps women who aren’t ready for a long labor to get through it.

"Women expect to come in and deliver in a few hours," she says, "and what’s realistic is that most labors are 12-24 hours. Patients always think it’s going to be faster than it is."

There’s a culture of avoiding C-sections at Cambridge Hospital that goes beyond the medical benefits. Jessey Buinicki, the hospital’s nurse manager for maternity services, has been encouraging women to deliver vaginally for 20 years and has three daughters who are moms.

"It’s been very empowering, it’s changed them from girls to women almost," Buinicki says. "In our society we don’t look at that, we’re all clinical and everything, but still the basic idea that you’re giving birth to your child is huge and should have more weight than maybe it does."

Cambridge Hospital does not have a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, or NICU. So moms with high-risk deliveries who go to Cambridge would likely be sent to another teaching hospital in Boston, such as Tufts Medical Center, which does have a NICU.

Dr. Sabrina Craigo, the director of maternal fetal medicine at Tufts, says the NICU helps explain why its C-section rate is 30 percent.

"We do 1,100 to 1,200 deliveries a year and at least half of those are high risk," Craigo says. "But those that are complicated, there’s just a higher risk of having a C-section."

Craigo sits in the hospital’s NICU amid tiny babies nestled in heated incubators, hooked up to tubes and monitors. Fifty-five percent of babies here, on average, were delivered via a C-section. Tufts, unlike Cambridge, does not use midwives. The hospital does make every effort, says Craigo, to avoid a C-section and she agrees that C-section rates are an important quality marker. But Craigo says comparing rates for smaller hospitals that are not equipped to care for premature babies and high-risk pregnancies may make more sense.

"Certainly the very high C-section rate in a community setting should raise your concerns," Craigo says, offering advice for pregnant women. "The 24 weekers [very early babies] are not being delivered in any of the community hospitals, so I think that is a distinction," between the community hospitals and Tufts or other teaching hospitals.

C-Section Research

But when researchers filter out the high-risk babies and just look at moms whose babies were in position for a normal vaginal delivery, some hospitals are still doing C-sections at almost three times the rate of other hospitals in Massachusetts. Why? No one seems to know.

Dr. Neel Shah, an OB at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, says time pressures in some hospitals may lead to more C-sections.

"The decision that we’re talking about is the difference between something that takes a lot of time and effort [a vaginal birth] and something that takes a lot less time and effort [a C-section]," he says.

Shah heads a new project that's mapping the decisions leading up to a C-section. It's under the guidance of Dr. Atul Gawande, whose surgical checklists have reduced complications and deaths around the world.

Shah says research shows that a physician's fear of a lawsuit does not explain the difference in C-section rates. Could it be that there are more older mothers, or more women having twins, or more women who are obese, or more women with a disease that complicates their pregnancy?

These factors may help explain why women are having C-sections, but they do not explain why some doctors do more C-sections than others. Shah is reviewing the theory that C-sections have risen with the use of fetal health monitors.

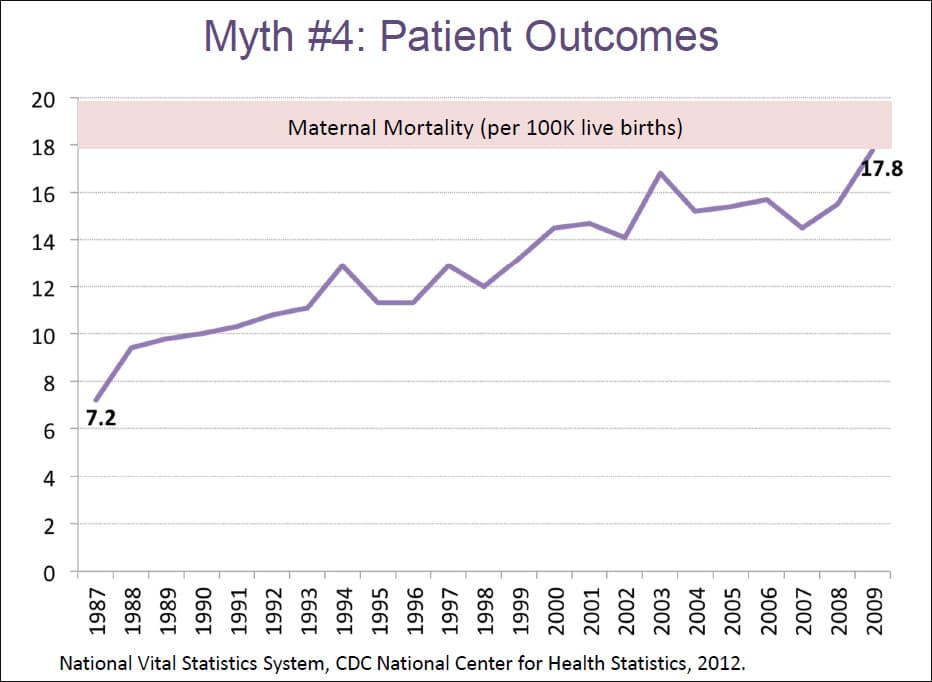

He told a roomful of physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess last fall that something is wrong with childbirth practices in the U.S. because, "You guys are on the only continent on the planet with an increasing maternal mortality rate."

Shah says there’s no proof that C-sections are the cause of rising death rates for moms during childbirth. There could be many factors. But researchers say the risk of ruptures and bleeding that increases with every additional C-section is under scrutiny. And hospitals are under increasing pressure to reduce C-sections. Public and private insurance plans are beginning to tie penalties or bonus payments to C-section rates.

There are many cases in which C-sections are the only safe way to deliver a baby. But if you are young and healthy and the hospital you plan to use does more C-sections than others in your area, you might talk to your doctor about why.

Check out our interactive tool to see how Cesarean section rates and four other childbirth quality measures differ at every hospital that performs deliveries in Massachusetts.

More: