Advertisement

If You Find A Tick: Why I Resorted To Mooching Pills To Fight Lyme Disease

I've never done anything like this before. I'm a good little medical doobie. I'm wary of pills, take them only with prescriptions, and follow the instructions to the letter. But last month, I "borrowed" a friend's extra 200 milligrams of doxycycline — the onetime antibiotic dose shown to help prevent Lyme disease soon after a prolonged tick bite.

What brought me to that desperate point? A doctor declined to prescribe the pills, even though this is prime Lyme disease season and the patient, my family member, fulfilled every one of mainstream medicine's requirements for the single dose aimed at preventing Lyme. To wit:

• The tick was a fully engorged deer tick that had been attached for more than 36 hours.

• We sought treatment within three days of removing it.

• The tick came from a Lyme-endemic area.

• And the patient had no medical reason to avoid antibiotics.

But still. The doctor argued that the chances of contracting Lyme from the tick were very small, perhaps 1 in 50, and that overuse of antibiotics contributes to the growing problem of drug-resistant bacteria. This is what he would do for his own family member, he said: skip the doxycycline, wait to see if Lyme develops, and treat it with a full 10-day course of antibiotics if it does.

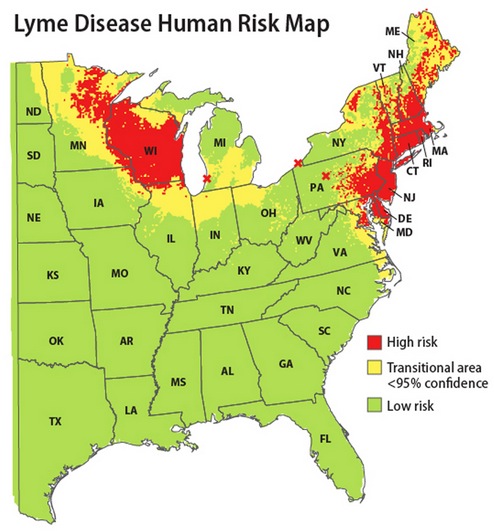

I was frustrated and frankly a bit appalled. WBUR ran a series on Lyme disease in 2012, and I knew that controversy raged around many aspects of the disease, particularly the use of long-term antibiotics to treat long-term symptoms. But I was just trying to follow the widely accepted guidelines written by the Infectious Disease Society of America, to be found in reputable medical venues like UpToDate. And I knew from that same series that Lyme is rife in New England, and so are personal stories of health and lives ruined or seriously harmed.

Still, maybe I was overreacting? I've since sought a reality check from three experts, including the lead author of the guidelines. And here's what I come away with: No, I was not unreasonable in seeking the preventive doxycycline. Arguably, though I hate to admit it, the doctor was not being totally unreasonable in declining it. The guidelines say a doctor "may" prescribe the antibiotic; it's not a "must."

In the end, I think, the crux of the question may lie in how you see the doctor's role: Is it to lay out the risks and benefits and then let the patient choose? Or to impose his or her own best medical judgment on the patient? (You can guess where I come down on that one.) Also, "better safe than sorry" tends to rule when it comes to my loved ones. But what if the risk is small and the benefit uncertain?

I spoke first with Dr. George Abraham, governor of the American College of Physicians for the state of Massachusetts, a practicing primary care physician and infectious disease specialist, and a professor of medicine at UMass Medical School:

He described the preventive use of doxycycline if all the guideline requirements are met as "Good medicine — scientifically based, it is absolutely sound."

So why might a physician refuse, and is such resistance widespread?

"There might be a minority of physicians who still feel it might be inappropriate for one of two reasons," he said. "Either concerns of antimicrobial resistance — although a single dose of antimicrobials is very unlikely to breed resistance, so that might be a bit unfounded — or just lack of awareness."

I confessed my pill-cadging peccadillo and he responded that it is simply not good medicine to use somebody else's prescription. "But I think the moral of the story is, if the person in question knows that they’re appropriately asking for an agent and don’t get it, I would seek a second opinion, see a different physician, use a local emergency room," he said. "Most emergency rooms are pretty savvy on this, just because they deal with this on a more frequent basis. Or even ask for a referral to an infectious disease specialist. It should be relatively easy. But the short answer is, there are ample other ways to get the medication."

I spoke next with Dr. Alfred DeMaria, medical director for the Bureau of Infectious Disease of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. He listened to my tale and began with the evidence base:

"There’s one published study on which the recommendations are based and that was a study — I think there were 200 to 250 people in each group, where they treated some people with 200 milligrams of doxycycline after tick attachment and others with placebo. And they found for the people who had an engorged tick — not for people who just had the flat tick attached, for people who had the engorged tick, where the estimation was that the tick could have been attached up to 24-to-72 hours — there was a reduced likelihood of Lyme disease developing if they got the 200 milligrams of doxycycline. Of course, there was also a 30 percent adverse reaction in those who got the doxycycline. I think that needs to be incorporated into the decision. But ultimately it's the only study that has shown that.

It’s generally felt that if it’s an engorged tick, there are two options: One is to treat with 200 milligrams of doxycycline and watch for Lyme disease. Or just watch for evidence of Lyme disease in terms of a rash. That’s sort of what the recommendation is on our website.

I think what happens is, there are competing concerns about drug reactions and about antibiotic resistance which counterweigh the decision to use the doxycycline, although 200 milligrams of doxycycline is not a lot of antibiotic therapy. But I think sometimes what happens in the community is that people have a tick attachment and no matter how long it's attached, they wind up on two weeks of doxycycline, which is really not recommended.

The other thing you have to consider is the risk of an individual tick being infected. What's good there is that we have Dr. Steve Rich at UMass, who's been testing ticks, and people on Cape Cod who've been testing ticks, and infection rates can vary from year to year, from place to place, anywhere from 5 percent to 50 percent of the ticks. What we’ve learned from some people on the Cape is: They collect ticks from the same place every year, and from year to year it can vary from 5 percent to 50 percent. And it can be 5 percent on one side of the road and 50 percent on the other side of the road. It is highly variable.

The worst probable chance is a roughly 50 percent chance the tick is infected, but that also doesn’t mean every tick that’s infected is going to transmit the disease. So it's a complicated situation, and I can understand a clinician going one way or another.

I think in an ideal situation a clinician would discuss it with a patient and they would make a judgment about how much risk they wanted to take and come to a conclusion that way. Unfortunately, the health care delivery system does not allow a lot of time to do that. But I would understand why a clinician would be resistant to doing it and I can understand why a clinician would want to do it under the circumstances that we recommend considering it.

It truly is a judgment call. I think some people would argue if the chances are only 1 in 10 or 1 in 20 that you'll get Lyme disease from that tick, you could watch for signs, because early treatment is highly effective, and you could avoid unnecessary antibiotic use. That's why we sort of say you should consider either option."

One thing is clear, Dr. DeMaria said: Lyme disease is a huge problem and "this is prime time," when the young "nymph" ticks are out looking for their "blood meals." So "the best course of action is to avoid ticks, or do those tick checks."

For a final word, I spoke with Dr. Gary Wormser, lead author of the IDSA guidelines and chief of infectious disease at New York Medical College. He, too, listened to my tale, and then began with how the team at the Lyme Disease Diagnostic Center at New York Medical College would have reacted:

"If you came to us and said you had the tick bite but didn't have the tick with you, [then we'd advise] no prophylactic antibiotics. If you had come to us with the tick and we could confirm it was actually a deer tick and it was on you for at least 36 hours, the prophylaxis could be started within 72 hours of tick removal and there were no contraindications to taking doxycycline, we would have offered you the 200 milligrams prophylactically, informing you that it would not necessarily be 100 percent effective and you should still be wary of the possibility of getting Lyme disease and/or other tickborne infections. I don't know the infection rate of deer ticks where you were, but in our area now 25 percent of the nymphal stage deer ticks are infected.

We have a lot of people who come in here and say they have engorged ticks and then we actually look at the tick, and it isn’t even a tick, or if it's a tick it’s not a deer tick. We've had all kinds of things brought in to us, from scabs to thorns to beetles to pubic lice — you name it, we’ve seen it. And also, the patient's concept of whether it's been on for at least 36 hours isn't very accurate, in our experience.

So it is a little bit tricky. That’s why the IDSA guidelines actually say that routine use of antimicrobial prophylaxis is not recommended, and only under very special circumstances would it be recommended. And so if a person met all those circumstances, we would do it. I think it’s a very interesting question about the long-term implications in terms of antibiotic resistance, which we’re all having to deal with on a day-to-day basis as infectious disease doctors, but in terms of the individual patient with a tick bite, we're still offering prophylaxis under those very specific circumstances.

Keep in mind that pregnant women and children under 8 aren't eligible for the doxycycline. And we don’t think it's 100 percent effective either. So in other words, it would be a little misleading to people at times to believe that it’s 100 percent effective. It isn’t.

Let me give you some statistics you may not be aware of: The fact that you found the deer tick means the odds overall of getting Lyme disease, having done nothing more than finding the tick, are 2.2 percent. If you take doxycycline, the risk of Lyme disease goes from 2.2 percent to 0.8 percent. But the confidence interval — the range of potential possibilities — varies from .02 percent to 2.1 percent. So in other words, it has been shown to be effective but unfortunately the study that was done, which was a pretty large study, wasn’t large enough in terms of numbers of cases of tick bites that were prevented to narrow down the exact efficacy rate. It was 87 percent effective but it could have been as low as 25 percent effective based on pure statistical variation.

So it's very important to understand the limitations. We know it has some efficacy and we know it's not like giving a full course of antibiotics. There are data that if you gave patients a 10-day course of antibiotics it would be essentially 100 percent effective. We knew that was being done, but we just didn't recommend it because, why would you want to treat every tick bite as if the patient actually already had Lyme? The beauty of this [200-milligram dose] was that it's only a single dose and it has, at least in the study that was done, over 85 percent efficacy. It’s just that we couldn’t be precise, we couldn't give a precise efficacy rate in what we call the 95 percent confidence interval surrounding the actual efficacy, meaning it could be less effective than that."

Dr. Wormser confirmed that the preventive doxycycline is a reasonable approach, if you fulfill the requirements. And some more reassurance: Just finding the tick means you're ahead of the curve.

"There are two ways to look at this," he said. "One way is to say that if the efficacy study we did was 100 percent accurate, that you have an 87 percent further reduction in the risk of getting Lyme disease. Or you can look at it this way: It's 2.2 percent risk going down to 0.4 percent or in that range. So if you look at it in those absolute percentages, it doesn't seem as dramatic."

I must say, those numbers calmed me down quite a bit. But even a small chance of a frightening possible outcome seems worth trying to head off.

Dr. Wormser understood. "First of all, everything to do with Lyme disease is anxiety-provoking," he said. "That's the nature right now of the reputation that this disease seems to have. So that's one of the reasons we offer this service, in part — not that we think it's the end of the world if the patient should get a rash at the site of the tick bite, because then we just give them 10 to 14 days of an appropriate antibiotic and everyone gets better. It's just that given the circumstances — the reputation and implications that people have drawn about this disease, whether they're accurate or not — it has caused so much anxiety and concern for many people that we're happy to offer the service of telling them yes, you might benefit from the 200 milligrams."

Well, if we lived in New York, I'd have been happy to receive that service for my family member.

Readers, what would you do? Say you meet all the requirements, would you want the single dose of antibiotics? How far would you go to get it?

Further Reading: