Advertisement

Let's Explore Diabetes With Honeybees (Seriously — It Could Work In Urban Slums)

The latest book by humorist David Sedaris is implausibly titled "Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls." But as we all know, life is stranger than literature: Now, an imaginative team of social entrepreneurs has devised a way to explore diabetes with bees — that is, to train honeybees to diagnose hidden cases of diabetes.

It’s no crackpot idea. It’s in the running with five other finalists for a million-dollar prize given each year by the Clinton Foundation.

Here’s the concept: Bees are 10,000 times more sensitive to chemicals in the air than humans. The breath of humans with diabetes contains higher levels of a chemical called acetone. Bees are easily trained to stick out their tongues when they detect a certain concentration of acetone.

Put a bunch of these trained bees into tiny harnesses, have a person breathe into a straw aimed at the constrained bees and voila! A diabetes screening system that doesn’t require laboratories, expensive machines, highly trained technicians, dietary fasting, or more than a modicum of money.

It may be a good way to screen large numbers of people for undiagnosed diabetes in developing countries such as India, where the disease is burgeoning even faster than in overfed America.

“Millions of people aren’t aware they have this disease,” says Juliet Phillips, a leader of the project, called "Bee Healthy." “They aren’t even aware there is this disease. So there’s a need to screen people for diabetes that’s free for people in slums but also culturally acceptable.”

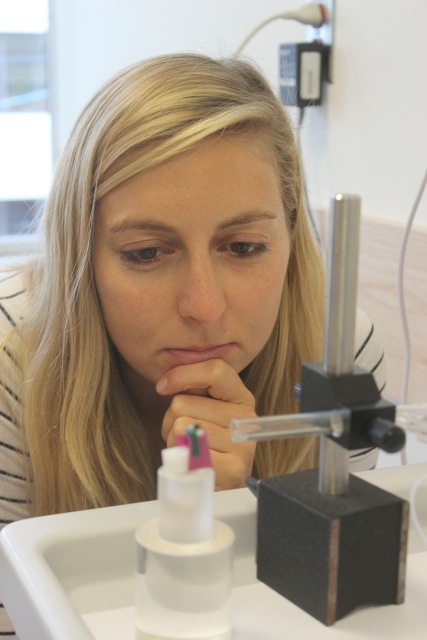

Phillips and her colleague Tobias Horstmann were in Boston this month to test the idea on a group of people with known diabetes. The experiment, at the Joslin Diabetes Center, found that bees could identify the diabetic patients 70 percent of the time.

“That’s not as high as we want to go, but we believe we can get there,” Horstmann says. “We can get improvement in the training of bees.”

In addition, the Boston patients in the test all had well-controlled diabetes, so the level of acetone in their breath was much lower than undetected diabetics in a developing country whose diabetes is out of control.

“So it will be easier for a bee to detect diabetes in an urban slum,” Horstmann says.

Horst, from Germany, and Phillips, a New Zealander, met at the Haute Etudes Commerciale de Paris, a business and management school where they earned masters degrees in sustainable development.

In January, the Clinton Foundation’s Hult Prize issued this year’s challenge: solving non-communicable disease in the urban slum.

The million-dollar prize –- intended to provide seed money to develop the winning project –- will be awarded in New York City on Sept. 23. The six finalists were chosen from over 2,000 applicants.

Phillips and Horstmann are currently testing their trained honeybees in Mumbai’s biggest slum. They say they were attracted to diabetes because it’s such an enormous and growing problem. The World Health Organization says nearly 350 million people have diabetes, and 80 percent of diabetes deaths are in low- and middle-income countries.

Another attraction was that treatment of diabetes is effective and relatively cheap –- unlike, say, cancer care. “Follow-up treatment can be partially done through more physical exercise and changing nutrition,” Phillips notes. “So it makes sense to tell a person he has diabetes because he can actually take action.”

Phillips and Horstmann also think their trained-bee system can be adapted to screen for other diseases, such as tuberculosis.

“There’s already a huge field of research on breath analysis,” Horstmann says. “There are biomarkers for cancer, TB, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary hypertension and many other diseases.”

And, it turns out, they didn’t have to invent the technology of bee training and detection. Bees have already been used to sniff out explosives and illicit drugs.

Robert Wingo of the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico is an expert in this field. He came to Boston recently to help Phillips and Horstmann learn how to put the bees in harnesses and train them to signal when they detect a certain level of acetone in people’s exhalations.

“We knew it worked in theory,” Horstmann says, “but the bee training we did in Boston for the first time was actually quite easy.”

In classic Pavlovian conditioning, the bees are given a sugar-water reward for sticking their tongues out when they detect a certain level of acetone. The bees’ response can be detected automatically by a camera system, but it’s also visible to the naked eye.

Dr. Allison Goldfine of the Joslin Diabetes Center says people with diabetes have more acetone in their breath because their cells are starved for sugar, so they burn fat for energy, and acetone is a breakdown product of fat metabolism. The less their disease is controlled by insulin and other drugs, the more acetone they exhale.

Acetone gives diabetics a so-called “fruity” breath, a classic sign of the disease.

Goldfine, Joslin’s head of clinical research, says she was originally skeptical of using bees to screen for diabetes.

“My original thought was that the concept was innovative but a little out there,” Goldfine says. “But once I saw it first-hand, I thought it might work. And I’m the most pessimistic person you’ll ever meet.”