Advertisement

What To Expect When You're Birthing At Home: A Hospital C-Section (Possibly)

By Ananda Lowe

Guest Contributor

The term “homebirth cesarean” didn’t exist before 2011, when Oregon mother and student midwife Courtney Jarecki coined it. But now, a Google search returns almost 2,000 entries on the topic.

The term refers to a small but emerging community of mothers who have experienced the extremes of birth: They'd planned to have their babies at home, but ended up in a hospital, most often in the operating room having a cesarean section, major abdominal surgery. Needless to say, the effect of such a dramatic course change takes a toll, and can often be overwhelming.

("Homebirth cesarean" can also refer to births that were planned to occur at a freestanding birth center outside of a hospital, but eventually were transferred to the hospital for a cesarean.)

How often does this happen?

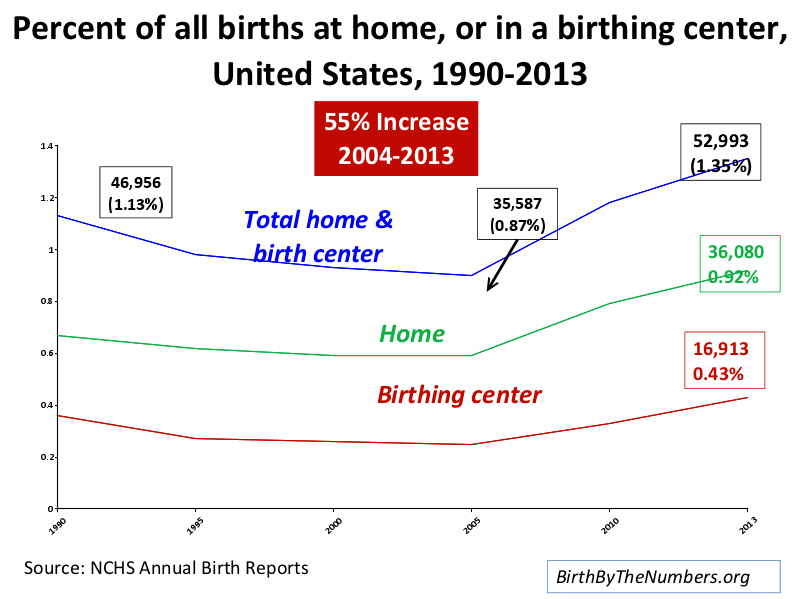

Home births, though a small fraction of the approximately 3.9 million births a year in the U.S., are on the rise. Based on the most recent birth data from the National Center for Health Statistics, "the 36,080 home births in 2013 accounted for 0.92% of all U.S. births that year, an increase of 55% from the 2004 total.”

Eugene Declercq, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University School of Public Health, studies national birth trends. He said in an email that while there are no nationwide numbers on homebirth transfers to the hospital, "the studies that have been done usually report about a 12% intrapartum transfer rate."

But beyond the numbers, what happens emotionally when your warm and fuzzy image of natural childbirth in the comfort of home suddenly morphs into the hard reality of a surgical birth under fluorescent lights?

Jarecki founded the homebirth cesarean movement to figure that out. She connected women who, like herself, shared the experience of giving birth through full surgical intervention, despite their original plans of having their babies at home or outside of the established medical system.

In Jarecki’s case, she labored at home for 50 hours until her midwives detected a rare complication known as a constriction ring, or a thickened band of tissue in her uterus that was impeding progress. Shortly after this, meconium appeared, and Jarecki knew it was time to go to the hospital. Her emotional response to the intensity of the situation, however irrational, was one of anger, shame and failure at her ability to give birth normally. A cesarean followed.

Over the next several years, Jarecki began helping other homebirth cesarean mothers emerge from the silence and shame they felt confronting their unexpected surgeries. Some of these women also report that their postpartum recovery was tougher because their unique needs were not adequately addressed by their home birth midwives or their hospitals.

Jarecki started by launching a (now busy) Facebook page as a support group for these mothers and their health care providers.

Childbirth Expectations vs. Reality

Rule number one in childbirth is that it rarely unfolds as you expect.

For many of us who give birth in today’s strained health care climate, there can be a major disconnect between childbirth as it’s idealized, and maternity care as it is actually practiced. Sometimes that divide is difficult to talk about.

We often dream of tender, individualized care from our health and birth team on the most important day of our lives. I felt this way when I had my daughter at a Harvard teaching hospital four years ago — but I disagreed with my nurse-midwife’s decisions that day, and I’ve felt conflicted about the events of my labor ever since.

Also, as a longtime doula and childbirth educator, I’ve observed that many pregnant women with understandable anxiety about cesareans hold the view that it-just-won’t-happen-to-them.

In reality, some women’s births match their expectations, some don’t. Studies from Australia, Belgium, China, France, Saudi Arabia, the U.K. and the U.S. concur: when expectations match experience, that's the single the most important factor in a woman’s ability to emotionally integrate the reality of childbirth. It's not, as you might expect, about how painful labor was.

And unplanned cesareans have been linked to a higher risk of postpartum depression, researchers report.

For mothers transporting from home birth to hospital, there's additional stress. Often the transfer happens without even a suitcase packed in advance. Adding to the potential trauma is the lack of an integrated system for home birth professionals to have hospital privileges or official relationships with doctors (at least in the U.S.); and perhaps the family’s psychological investment in avoiding a hospital in the first place by choosing to birth at home.

A Cambridge mother, Susan (who asked that her last name not be used) planned for home births, but ended up delivering her second child by cesarean at a hospital in 2011. She says: "I can understand the variety of emotions that come with 'failed home births.'"

Women and Their Midwives

This week, Jarecki came out with a self-published book called "Homebirth Cesarean: Stories and Support for Families and Healthcare Providers," along with a companion workbook for mothers.

I've been following Jarecki's work for years, and I get it. As a longtime doula (professional childbirth coach) in Massachusetts, I’ve felt my own loss of words in helping some of my clients find resolution when their births resulted in unplanned medical treatments and/or cesareans. And often, it's the close bond between birthing mothers and their midwives that unravels after a home birth has gone awry.

Margaret Rosenau of Louisville, CO said in an interview that she tried to talk to her home birth midwives multiple times after giving birth about her disappointment in some of their actions. She says they refused to acknowledge her point of view, and told her she should see a therapist to discuss her over-reaction.

Jarecki describes her immediate postpartum experience this way:

[Our midwives] Laurie and Kim made several extra home visits for two weeks after the birth, then regular postpartum care resumed. I felt comfort and confusion in their presence. Though I was invited to process the birth with them, there was an unspoken story between us, something no one wanted to talk about. My mind was in a state of chaos, both frenzied and vacant, and I was unable to ask for what I needed because I wasn’t sure what would help.

And her midwife, Laurie Perron Mednick, adds:

Walking with clients through difficult births is heart-wrenching work, and I did not yet have the wisdom to process my own feelings about homebirth cesareans. The result was that I carried layers of guilt, uncertainty, and unresolved grief into each birth I attended, and this baggage sometimes felt like a wound that never completely healed.

Nearly a year after she gave birth, Jarecki approached her midwives again and began a dialogue about the ways in which her needs had not been met, especially regarding her postpartum physical and mental health.

Going To Plan “C”

The book Homebirth Cesarean offers a unique contribution to the literature about care and support for women before, during and after childbirth. Chapters offer extensive suggestions about how to prepare any mother-to-be for the chance of an unexpected cesarean.

The bottom line: Talk about it in advance, in spite of any discomfort or resistance on the part of parents or midwives.

Jarecki and Mednick (her midwife and a contributing author) provide dozens of talking points to get these conversations started.

For instance, if a transport to the hospital is needed, mothers interviewed for the book expressed a need for their home birth midwives to stay engaged as advocates. Jarecki advises how this can happen:

A mother in the hospital relinquishes control of her labor, her body, her baby, and now she must contend with numerous interventions. She may feel unable to stop the train of madness that she perceives her birth is becoming, and she may surrender her decision-making autonomy. Furthermore, hospital staff rarely recognize and acknowledge the mental, spiritual, and emotional pain of a transport. Often they simply see a homebirth mother who might be difficult to work with because she is protesting interventions. But when hospital personnel do recognize the distress of transport and other choices in her care whenever possible, the mother can feel that she maintains her dignity and her right to self-determination.

With the guidance of her birth team, a mother can focus on her highest intention for the birth, and she can clarify and communicate her non-negotiables. For example, if she asserts her choice for no cervical checks without consent, being in the hospital can feel less like giving in, since her self-determination and power to negotiate for her needs are maintained. A laboring woman needs her partner and her birth team to help her advocate for her choices. Her midwife and doula can guide her as she asserts her right to respect, privacy, and safety. HBC mother Ann says, “I’ve wondered so many times why my midwives or doula didn’t remind me that I could have said no to all these strangers giving me rough vaginal exams. No one said that to me, and I really wish they had.”

As a doula myself whose training touched upon, but did not emphasize, planning for unexpected events in birth, I truly appreciated the following message from the book: As professionals, we can inform parents in our care that the reason we insist on cesarean preparation is that the risk of a cesarean turning traumatic rises sharply if the topic is ignored prenatally, but the procedure is ultimately needed.

Postpartum

In today’s maternity care, no one is officially assigned the role of helping families plan for their postpartum adjustment. (And what an adjustment it is!)

A midwife, doula, or birth class instructor may be the only person who can realistically take on this job (and many families don’t have access to those professionals). According to the book, this kind of strategizing before birth must be intentional, or there's a good chance it won't happen at all. (Particularly in the case of a cesarean, which means recovering from major surgery while caring for a highly dependent newborn.) Planning for household chores, lactation guidance and mental health bolstering should be sorted out in advance.

For families whose reality includes a homebirth cesarean, recovery comes through telling their story, Jarecki says. Not just once, and not in the way that will make others around them most comfortable. Some will integrate their experience more easily and quickly, while others will contend with normal feelings of self-blame or shame at not “succeeding” in fulfilling their original expectations.

According to Jarecki and Mednick’s findings, these strands of the birth story need to be examined one by one, and each statement a woman has latched on to — about her self-worth, for instance — must be be faced and reframed.

The International Cesarean Awareness Network (ICAN) is a nonprofit that aims to provide support and education about cesarean section. Kira Kim, leader of ICAN of Eastern Massachusetts, runs monthly meetings. She says when the topic turns to homebirth cesarean and emotional recovery, attendence is typically high. "It's a safe place where women can be heard and validated, where these difficult conversations can be had openly and with respect."

Sue Burns, a mother whose birth story appears in the homebirth cesarean book, says:

Because I got the “at least your baby is healthy” comment so often, so quickly, I immediately sequestered myself. I did not want to hear that...line. I felt invalidated. I did not want to look anyone in the face. I did not want anyone to see my shell-shocked, terrorized eyes and say, 'But you are alive!' I wanted and needed someone to say, 'You are incredible. You are so strong. You are a mother. You obviously have out-of-this-world endurance and resilience!” Or better yet, “Yes, it hurts. It sucks you didn’t get to birth at home. I’m here for you.' I finally was able to say those things to myself. I labored at home for a ridiculously long time. I endured. I had stamina and an unbelievably high pain tolerance. And then I did the thing I most didn’t want to do: I went to the hospital. I was brave enough to let someone cut me open and have major abdominal surgery AWAKE! so that I could be her mother. I am a warrior.

Readers, have you experienced a homebirth cesarean? Tell us your story.

Ananda Lowe is co-author of 'The Doula Guide to Birth: Secrets Every Pregnant Woman Should Know' (Bantam Books) and a student nurse living in Somerville, MA.