Advertisement

Cancer Haves And Have-Nots: Care And Treatment In 2 Different Worlds

Imagine feeling a lump on your body, visiting a doctor, and then waiting seven months (if you're lucky) to find out whether it is cancer.

This has been the reality for the vast majority of patients in two of the world’s most impoverished nations, Rwanda and Haiti — both emerging from different but unthinkably grim histories of structural violence.

But since 2012, more patients are getting the care that everyone deserves, no matter what country they live in. A medical partnership between several Boston-based hospitals has radically reduced turnaround time for cancer diagnosis, and shrunk the number of people who fall through the cracks.

It is difficult to quantify the exact numbers here, since record keeping in the past has been poor. One data point: In Rwanda, where these interventions are in place, far fewer patients are lost to follow-up after they've been treated compared to patients in other poor countries, according to Dr. Larry Shulman, senior vice president for medical affairs at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and leader of the medical partnership.

As a pathologist at of one of these partner institutions -- Newton-Wellesley Hospital -- I can't help but think about the patient behind the slides under the microscope. Here's one: Tushime, an 11-year-old Rwandan girl, who had a large tumor protruding from her jaw.

The tissue sample from Tushime's tumor arrived in Boston in a suitcase carried by an employee of Partners in Health, the global nonprofit. Like all other specimens, hers was processed into a slide by the pathology department of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and read by Harvard faculty.

Tushime’s tumor turned out to be a rhabdomyosarcoma, a common childhood sarcoma. After 48 weeks of chemotherapy and surgery in Rwanda, she is now healthy and free of disease. Doctors there used standard chemotherapy for a cost of about $300 (which was covered by Partners in Health, Dana Farber and the Rwandan government). They relied on age-old, tried and true chemotherapy drugs; in comparison, the newer chemotherapy agents in the U.S. often cost several thousands of dollars.

Even though access to care has improved dramatically in the developing world there is so much work to be done. There are patients who still present with tumors at an advanced stage, many being neglected for months or even years because of barriers to care. There's often a lack of access to facilities for both diagnosis and treatment, and funding for cancer care is limited. As a result, ordinary diagnoses become extraordinary.

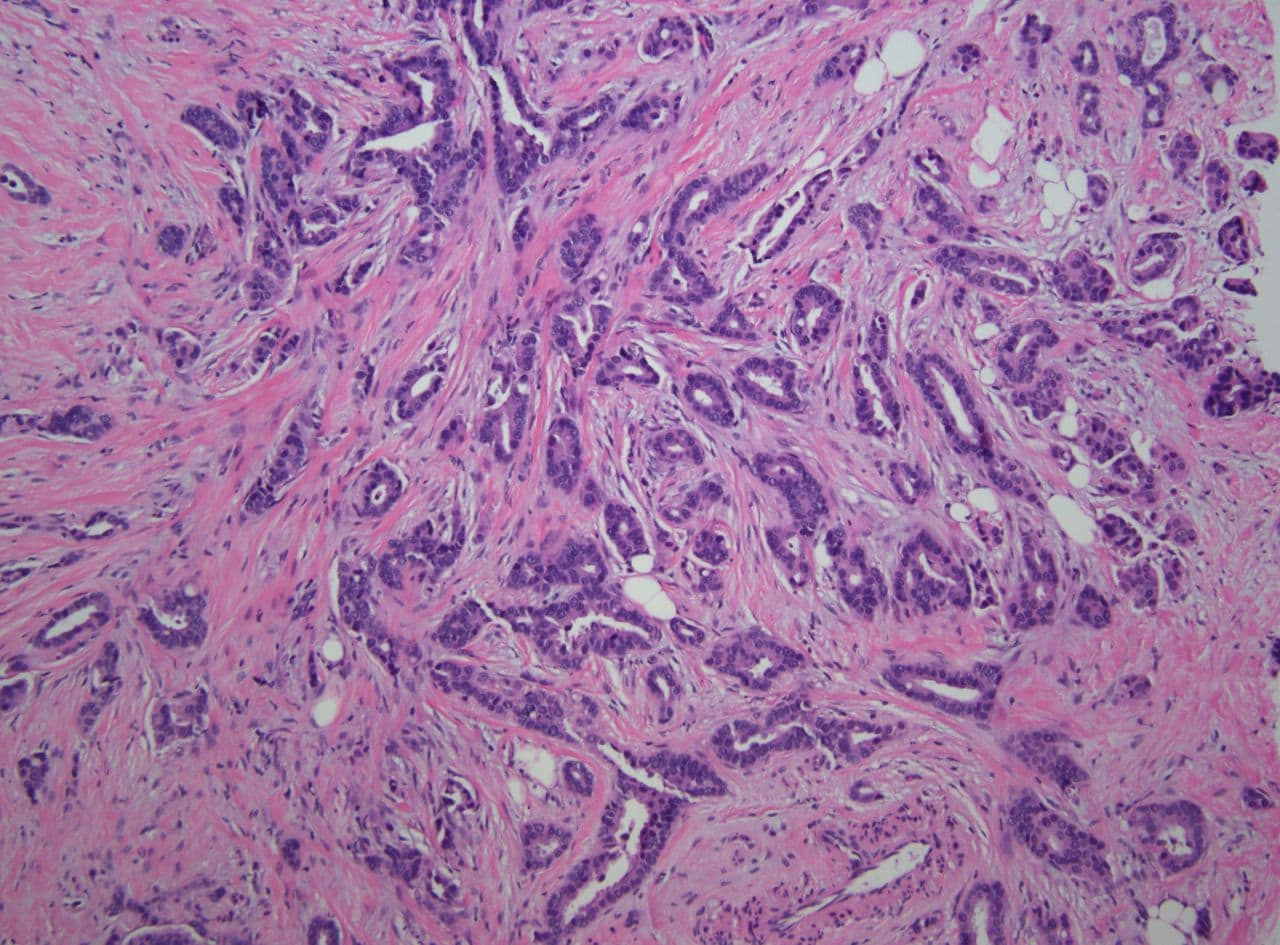

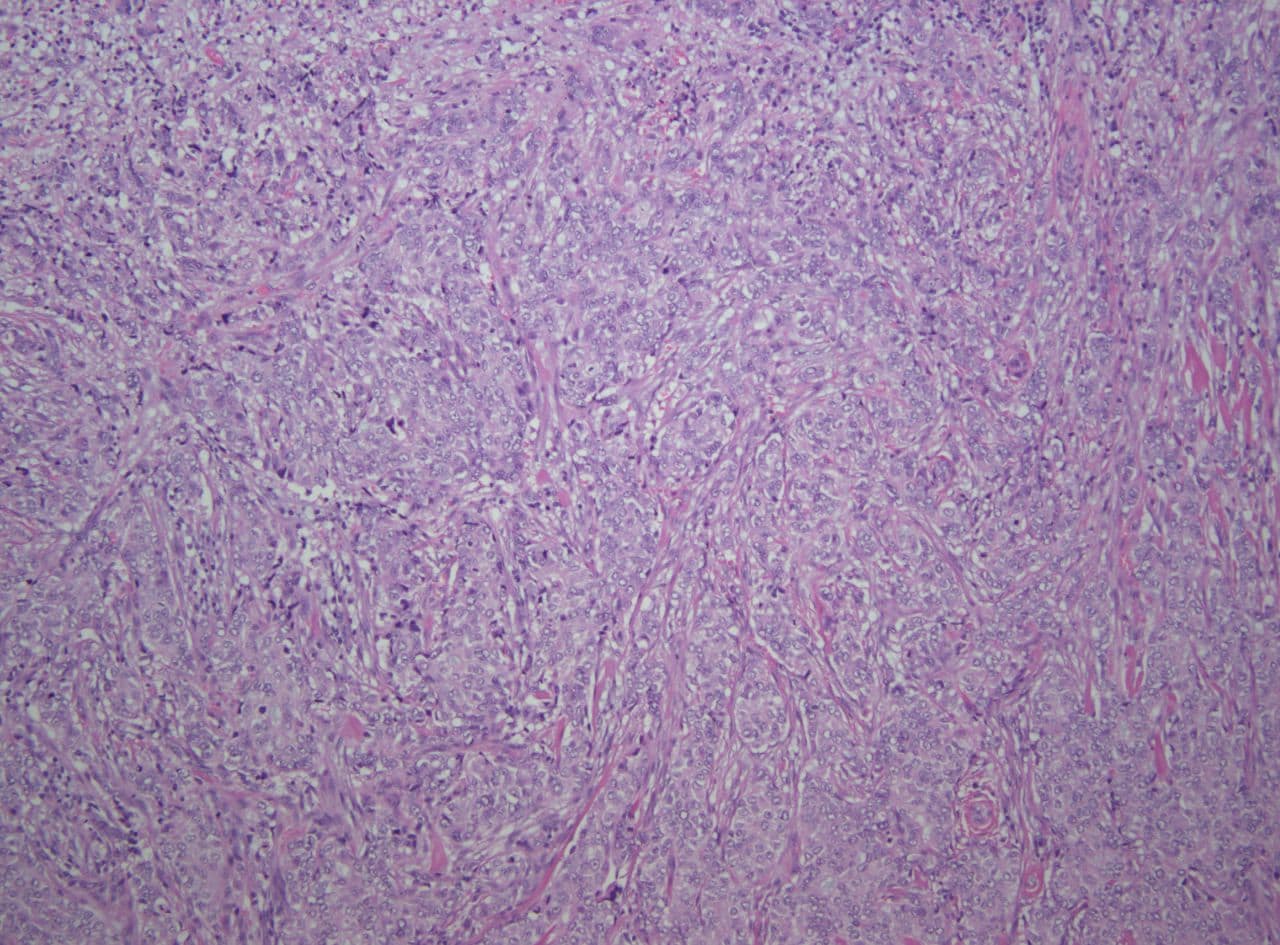

Under my microscope, I've seen some of the most aggressive appearing tumors from patients in these countries. What are typically rare cancers here in the U.S., such as sarcomas or unusual variants of breast cancers, are all too common in developing nations.

By far the most common adult cancers seen in Rwanda are breast and cervical. In the U.S, breast cancer is the No. 2 cancer in women (after skin cancer), however many are caught early as a result of effective screening. Invasive cervical cancer is very rare in the U.S., not even ranking among the top 10. Among children, Wilm’s tumor (a kidney tumor, extremely rare in the U.S.) is one of the most common cancers in Rwanda. Some diseases cross boundaries, however: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a common cancer both in Rwanda and the U.S.

With limited clinical information, workups in Haiti and Rwanda can be challenging. As a doctor in the U.S., I can, with a few keystrokes, easily uncover valuable information about my patient’s history, lab tests and radiology studies. We are far from perfect here, that's true, and one could argue that we sometimes go too far in treating disease here. But that's another story. At least there exists fairly close integration of care for U.S. cancer patients -- pathology, surgery, imaging, systemic therapy and palliative care. Once patients are within the doors of the hospital, pathology is almost always the first line of defense. Although this is something we may take for granted in the developed world, a diagnosis equates to treatment and often survival. To paraphrase Dr. Dan Milner, associate professor of pathology at the Brigham: A missing cog in the wheel results in a wheel that doesn't turn.

It is no mystery why low income countries have a higher incidence of cancer and higher death rate due to cancer: Many of the poorest countries lack an oncology program entirely. According to the World Health Organization only 5 percent of global resources for cancer are spent in the developing world. Limited resources mean limited access to doctors, medicine, followup care and medical record keeping.

With a capacity to perform only basic surgery, understaffed operating rooms and limited radiology equipment, countries such as Haiti and Rwanda face many challenges. Access to diagnostic imaging, radiation therapy and other complex components of treatment are often available only miles away and sometimes across borders. Issues such as safe storage, preparation and administration of drugs present added problems. Electrical problems and spotty Internet service render electronic medical record keeping difficult.

Our partnership has big plans: Central to any long-term collaboration are capacity building and infrastructure expansion. So, in 2012, a fully functioning anatomic pathology laboratory was installed in Rwanda, and two Rwandan technicians were trained at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) and the Brigham. Technicians now generate glass slides and special stains for diagnosis which are triaged by telepathology and interpreted locally or after transport to Boston.

In Haiti, the team recently broke ground on a pathology laboratory, the start of a improved access to better treatment and care.

I feel privileged to be a part of a movement providing global cancer care so that everyone, despite their income, can have access to cancer medicine and treatment.

As Dr. Larry Shulman, of Dana-Farber, has said: "If you want to have the biggest impact in reducing cancer-related mortality worldwide, you don’t need new scientific discoveries, but rather you need to bring the tools we currently have at our disposal to the many cancer patients who have no access."

Dr. Michael Misialek is associate chair of pathology at Newton-Wellesley Hospital and assistant clinical professor of pathology at Tufts University School of Medicine. The author thanks Drs. Shulman and Milner for providing content and images, and to Claire Wagner of the Dana-Farber Center for Global Cancer Medicine.