Advertisement

Amnesia Undone: MIT Study In Mice Restores Lost Memories

How's this for a grabber?

"Memories that have been 'lost' as a result of amnesia can be recalled by activating brain cells with light. In a paper published today in the journal Science, researchers at MIT reveal that they were able to reactivate memories that could not otherwise be retrieved, using a technology known as optogenetics."

Yes! Does this mean we can reclaim our long-forgotten halcyon childhood days with a bit of a laser boost to the right neurons? Um, no, not today. But it's still fascinating. That MIT press release quoted above goes on to explain that the study explores the difference between how a memory is stored — in a group of brain cells called an engram — and how it is retrieved. It quotes Nobel Laureate Susumu Tonegawa, who leads the group that did the work, on the evolving concept of what a memory is, in our brains:

“We are proposing a new concept, in which there is an engram cell ensemble pathway, or circuit, for each memory,” he says. “This circuit encompasses multiple brain areas and the engram cell ensembles in these areas are connected specifically for a particular memory.”

WBUR's Rachel Paiste spoke with Dheeraj Roy, a grad student in Tonegawa's MIT lab who worked on the research. Their conversation, lightly edited:

RP: So what did you find?

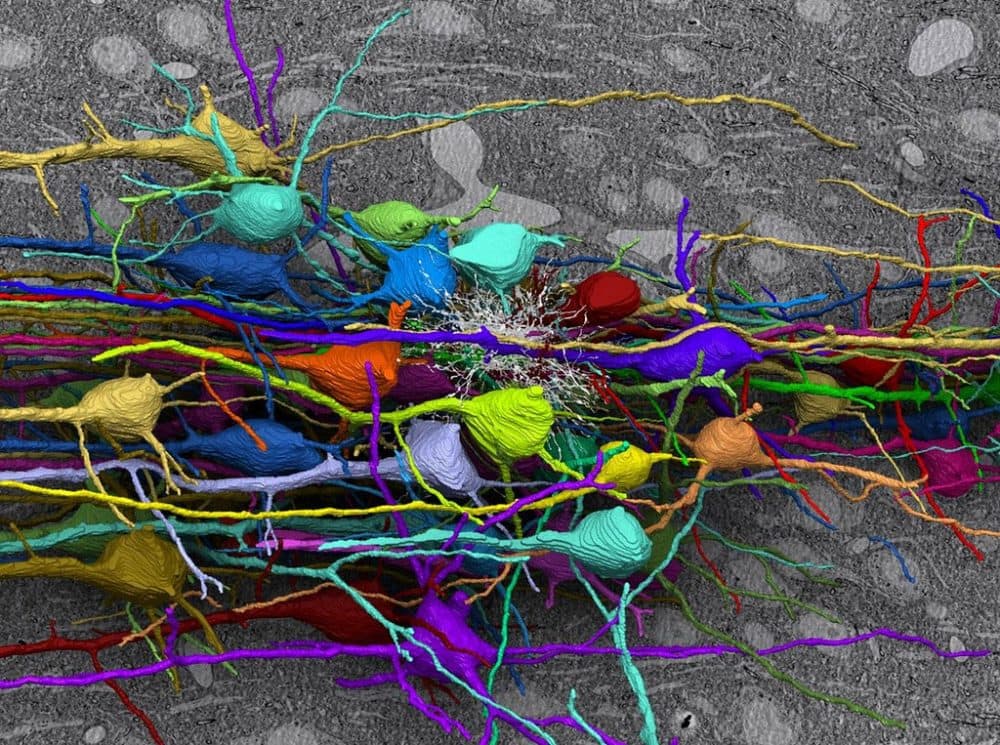

DR: We wanted to look at mouse models of amnesia, for the simple reason that there's very little done today in the field. So we attempted to look at individual memory traces, which we refer to as engram cells, which are sparse populations in several brain regions — the one we worked with is the hippocampus, which is widely known to be involved in memory. And we looked at: Do these memory traces, which we see in normal mice, do they still persist in amnesic mouse models? And if so, is there any way that we can restore or bring back these memories?

And this is actually stemming from a debate in the field: Neuroscientists weren't sure, when a mouse or a rat or a human can't remember a memory, is it because the memories are no longer stored or is it because for some reason they can no longer be accessed? So our study really started with that goal: Can we try to tease apart storage problems, where the memory is gone, or retrieval problems, where the memory is there but just needs to be retrieved somehow?

So our findings, I think for the first time, tell us that in certain models of amnesia, memories do persist and, very importantly, at levels similar to what we see in control mice. And that's actually what was most exciting for us: not just that memories persist — that's been known for a while — but the fact that we can bring back memories to equivalent levels as control animals is very unexpected.

So the first thing I thought of here, knowing more about pop culture than brain science, is "Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind." As far as retrieval of memories, is this something that could somehow become used for humans?

I think it will take more research and is years in the future. But if I had to describe how I think this work could be extended, the first thing that comes to mind is the mouse model of Alzheimer's disease — and in the future, human patients suffering from any sort of memory loss.

I think the first thing we have to do is make a system analogous to what we have with optogenetics, which is light control of neurons, to bring back memories. Could we use something like Deep Brain Stimulation, which is already being used for Parkinson's disease successfully, in human patients, as well as more recently in Alzheimer's disease?

So we think that studying the relationship between Deep Brain Stimulation and our specific memory activation in mouse models could give us insight into how this could be extended. If we could come up with a strategy that uses currently available techniques in the clinic, such as Deep Brain Stimulation, that would be fantastic and I think the implications would be amazing.

So what might this mean for people with Alzheimer's or amnesia or PTSD, a few years down the road?

There are several types of amnesia, so it's very important for us to first establish that in our model, we were able to find memories persisting. So that would be our first step: In the future, in humans, can we find out in what types of amnesia the memories persist? And once we do, it would be important to find a strategy to bring them back permanently — whether it be memories for a few years or for a decade. Whether amnesia is from PTSD or a stressful event or natural memory loss with aging — memory makes us who we are, and being able to bring it back is where I think the research is taking us. This is the first step but one of many.

Did you look at various types of amnesia?

We started with the most famous type of amnesia, which is this protein synthesis-inhibition-based amnesia. And it's important to keep in mind that it's been used in neuroscience for decades. So we wanted to use the most dominant model to try to get an understanding of what happens in this type of amnesia. In the future, we're looking at expanding this to applying it to the mouse model of Alzheimer's disease — where, I think scientists would agree, it is possible that memories do persist but no one has ever looked at single memory traces and how technology such as ours may be applied.

I know this would need research that hasn't happened yet, but does this mean that every memory you've ever had may be hiding somewhere in the dark corners of your mind, waiting to be retrieved?

That's a fascinating question. I wish I could say yes. The way I think of the brain is that memories that are important to us — time with family, a birthday, an eventful day at work, an awards ceremony — these are the sort of memories that, if I had to speculate, would be the most robustly persisting, or would last the longest. I'm not very sure about a day in the park or other memories that weren't as eventful. But it may be in the future that our technology could be applied to both, to tease apart which ones do persist.

What is most exciting to you about these findings?

To be honest, when we started this experiment, we actually thought that in amnesia, memories do not persist. Like all the other researchers, we thought they were just erased somehow. So the fact that we could unexpectedly be in the lab one day and shine the light in these amnesic mice and get memory retrieval — I still remember that day, and will for the rest of my life and career in research. It was just amazing to see something so unexpected happen, even though our professors and the other scientists in our building would never have guessed that were possible. That gets me excited and keeps me going.

And if you ever lose that memory, you know it can come back, with just a little bit of light!