Advertisement

After A Death, Crackdown On Drowsy Teen Drivers Led To Fewer Crashes, Study Finds

CommonHealth Intern

It was to be Maj. Robert Raneri’s last day of work before his wedding the following week. On June 26, 2002, Raneri, a member of Army Reserves, left his home in Nashua, New Hampshire for the Devens Reserve Forces Training Area in Ayer, Massachusetts. But he never arrived.

Raneri was killed by a 19-year-old drowsy driver who admitted to having stayed up through the night playing video games. Shortly after Raneri’s death, his fiancée, Maj. Amy Huther, learned she was pregnant with his child.

In accordance with Massachusetts law at the time, Drowsy Driving

But the tragedy brought attention to the problem of drowsy driving and, in 2007, led to new rules that govern the way young drivers grow into their adult licenses: the graduated driver-licensing program.

Those rules (amendments to already existing law) included stiffer nighttime driving penalties, driver’s education on drowsy driving and tougher penalties for negligent or reckless driving. And it seems the strict new rules have worked, dramatically decreasing the number of drowsy driving accidents involving teenagers, according to a new study out this month in the journal Health Affairs.

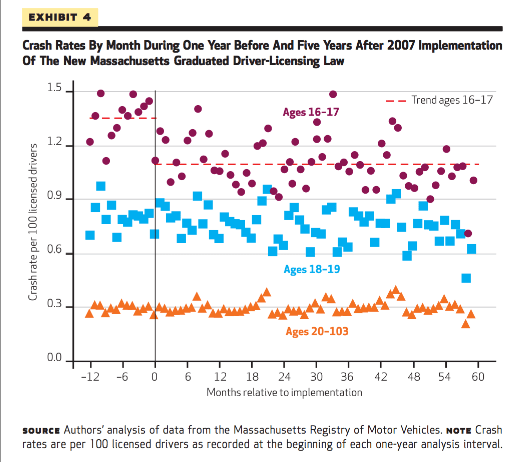

Indeed, the results are striking: Among junior operators (ages 16-17), the overall rate of car accidents fell by 18.6 percent, the rate of night crashes decreased by almost 29 percent, and there was an almost 40 percent decrease in car crashes resulting in a fatal or incapacitating injury, researchers report. The study focused on data from one year before and five years after the implementation of the new amendments.

Legal Crackdown

This is the first study of its kind to look at the effects of individual components of a driver licensing law, such as more exacting penalties, the authors state.

Dr. Charles Czeisler, chief of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston and co-author of the study, said in an interview that researchers are "confident that these features of the law were critical in the decline in the teen fatal and incapacitating injuries as well as the overall crash rate that we observed."

Like young drivers everywhere, Massachusetts teens don’t have the same privileges as adult drivers. They aren’t allowed to drive at certain times of night; they can’t have friends in the car right away; and they have to drive with a parent or other adult in the car when they’re first starting out.

That’s what a graduated driver-licensing program does: It requires young drivers, for safety’s sake, to gain experience and skills before they can enjoy the full freedom and independence that driving allows.

Every state in the country has graduated driver-licensing laws in place, the study authors note. But only 31 percent of states currently have night driving restrictions in place until at least age 18. In Massachusetts, however, the 2007 nighttime driving restriction became one of the toughest in the nation.

Before the 2007 amendments, Massachusetts junior operators were not allowed to drive unsupervised between midnight and 5 a.m., but the penalties for violating the restriction were comparable to a speeding ticket (no more than $100, and only $35 for a first offense).

Following Raneri’s death in 2002, Richard T. Moore, then a member of the Massachusetts State Senate and co-author of the new study, contacted Dr. Czeisler, who assembled a team of experts to develop model legislation addressing the problem of drowsy driving. In 2007, the nighttime restriction was adjusted. Currently, drivers caught violating the 12:30 a.m. to 5 a.m. restriction get their license suspended for a minimum of 60 days. With each additional violation, the suspensions get longer, maxing out at one year.

Saving Lives

These amendments to the Junior Operator License Law are estimated to have prevented around 320 fatal and incapacitating injuries and 13,000 motor vehicle crashes among Massachusetts teen drivers since the law took effect, Czeisler said.

The amendments were meant to decrease the incidence of fatigue-related crashes, which is a particular concern among teenagers. It might be counterintuitive, but teens are more likely to “fall apart” than older people due to sleep deprivation, Czeisler said.

“The common misconception is that younger people are strong and fit and therefore can more easily handle sleep deprivation,” he said. In a study where a young people and a group of senior citizens were kept awake for 40 hours, the seniors “did so much better on every measure.”

It might be that older people handle sleep deprivation better than young people because it’s naturally harder for them to fall asleep. It takes a certain level of cells activating in a region of the hypothalamus — the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, if we’re being scientific — to signal the transition to sleep. As people age, the cells in that area of the brain die, and it takes greater sleep pressure their sleep switch to ignite, Czeisler said.

Do Driving Habits Persist?

One key question about the restrictions is: Do the benefits last? If teens are trained to drive well under the threat of penalties, do they maintain good driving habits even when the penalties are off the table?

There isn’t a clear answer. Two years after the law’s passage, some members of the cohort moved from the 16- and 17-year-old group into the group of 18- and 19-year-olds, yet the 18- and 19-year-old group did not go on to experience the same marked decrease in crashes. (Among these older teens, the overall crash rate declined by 6.7 percent, according to the study.)

“We do have some evidence of the sustained benefit of the new law,” Czeisler said, but he noted that there is still work to do: 18- and 19-year-old drivers had the highest nighttime crash rate of the three groups.

The authors conclude that "state and federal policy makers should implement graduated driver-licensing laws that include restrictions on unsupervised night driving for all young drivers younger than eighteen as a primary offense…with strict penalties, including 60-day, 180-day, and one-year license suspension for the first, second, and third offenses, respectively."

“My hope would be that Massachusetts leads the way,” Czeisler added.

What You Need To Know About Sleep Deprivation And Drowsy Driving

Here are a few tips from Dr. Czeisler:

1. Being sleep-deprived is like being drunk.

One in five motor vehicle crashes are related to drowsy driving, and the fatalities associated with drowsy driving amount to about 75 percent of the fatalities associated with drinking and driving, Czeisler said.

The level of impairment you experience from being awake for 24 hours is equivalent to having a blood alcohol level of 0.1 percent, above the legal limit of .08 percent. It’s common to have a designated driver in place for a night of carousing, and you’re just as impaired when sleep-deprived.

In some ways, drowsy driving is more dangerous than drunken driving, because “when you fall asleep at the wheel, you don’t do any evasive maneuvers,” Czeisler said.

2. You can’t control when you fall asleep.

“Many people don’t realize that the brain can seize control when the sleep pressure is high enough,” Czeisler said. Make sure to pull over if you feel sleepy while driving.

3. Chronic sleep deprivation is as bad as pulling an all-nighter.

Sleeping for four or five hours per night for a week puts you at the same level of impairment as someone who has been awake for 24 hours, Czeisler said. Remember Tip No. 1: that’s equivalent to a 0.1 percent blood alcohol level.

4. The best way to fight sleep deprivation? Get more sleep.

“Make sleep a priority,” Czeisler said. Teenagers really need between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night, but they often try to get by on an adult schedule, leaving them chronically sleep-deprived.

5. Don’t rule out sleep disorders.

If you find yourself falling asleep even when you think you’ve caught enough winks, then it might be time to go in for a clinical evaluation to screen for sleep disorders, Czeisler said.

6. Read the labels on your medication.

Certain medications — like those for allergies and motion sickness — contain similar ingredients to over-the-counter sleeping pills and make you drowsy, Czeisler said. The “Don’t drive or operate heavy machinery” warning should be taken seriously.

7. You’re sleepiest in the morning.

It seems logical that we’d be sleepiest at night, before bedtime, right? In fact, that’s when we’re most awake, Czeisler said. For evolutionary reasons, we needed that burst of energy in the evening to find a safe place to settle down, and our desire to sleep is the strongest in the early morning. That’s not great news for people who face a morning commute and high school students who drive to school.

8. Beware of sleep inertia, aka morning grogginess

“It does take the brain at least half an hour to make the transition from sleep to wakefulness…the crash risk is greatly elevated the first 15 to 30 minutes after awakening,” Czeisler said.