Advertisement

When And Where Do You Stress? Ambitious Project Aims To Map Daily Life, Whole City

By Marina Renton

CommonHealth intern

Would I make it to the train station in time? Or would I miss my train home? The concern gnawed at me as I fidgeted on the uncomfortably warm and crowded subway platform. As I anxiously scanned the tracks for approaching lights, the watch on my wrist buzzed. It was telling me to check my stress levels. I pulled out my phone. High, it said -- surprisingly high.

That may sound like the first draft of a science fiction novel but, in fact, it’s describing events from last month, when I tried out a watch that has sensors to measure the autonomic nervous system, which regulates our fight-or-flight response.

Neumitra, a Boston-based startup, developed the technology, and plans to launch an ambitious project this fall that would use it to chart the stress not just of individuals but of professions and institutions — even of a whole city. It may be a no-brainer that catching a train is stressful, but how does stress at Harvard compare to stress at Northeastern? North Shore to South Shore? Emergency room at Boston Medical Center to Massachusetts General Hospital?

“We’re using data from the body and data from mobile phones to understand how everyone is affected by stress,” said Rob Goldberg, co-founder of Neumitra and a neuroscientist formerly at MIT. “Our aim here is for thousands of people in Boston to be using these technologies, so we can understand the difference between a veteran, a police officer, a student, a mother, a nurse — and sometimes you belong to multiple of these categories, so what are the combined effects?”

Sync To See Your Stress

“I’m so stressed!” is a frequent response to the innocuous, “How are you?” The exclamation, or variations thereof, can be heard at the office, between classes, at home…practically anywhere.

But it’s one thing to verbally express feelings of stress, and quite another to quantify those sensations. That’s where Neumitra comes in.

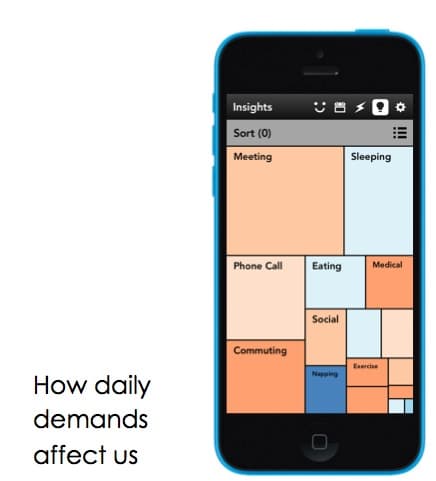

You can track your stress level in real time through an app that displays the data that the watch collects. The app syncs with your calendar and GPS, so you can also look back to see which events and locations cause the most stress. When your stress spikes, the watch vibrates — an alert that it might be time to take a step back and recalibrate.

"We don’t understand what we’re all struggling with on a day-to-day basis."

Neumitra co-founder Rob Goldberg

The app displays stress using a color gradient: Blue means relaxed or restful, orange and red signify increasing tension. During my entire subway ride, I was either in the dark-orange or red zone. Once I was back home, I spent more time in the blue regions. Exercise brought me back into the orange (among other things, the watch measures skin conductance and temperature, so physical exertion can register as stress), but it didn’t exceed the stress I demonstrated while standing (read: trying not to fall on anyone) in a crowded subway car.

This technology is certainly fascinating, but does it really tell us anything we didn’t already know? Goldberg’s answer is an emphatic yes. “We think we [know how we feel], but we’re very detached from that,” he said.

Science At A New Scale

In this age of “smart” or “connected” everything, we’re getting used to devices that monitor us, but Goldberg says Neumitra’s plans for the technology’s use on a large scale might lead to a whole new understanding of the effects of daily life on stress.

“We don’t understand what we’re all struggling with on a day-to-day basis, and with data of this type it allows it to become much more visible,” he said.

This coming fall marks the planned launch of the Boston Stress Study, which aims to “quantify brain health across an urban population,” according to its website.

Goldberg compared the Boston Stress Study with the landmark Framingham Heart Study, which began in 1948 with over 5,000 participants and continues to this day with subsequent generations. The Framingham Heart Study has been crucial to the identification of risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The data gathered as part of the Boston Stress Study will be aggregated, with the goal of showing the differences in stress level by profession and, in the long term, by socioeconomic status, gender, even university.

“We’ve all heard stories about what does it mean to feel stress at MIT, or Harvard, or at Boston University,” Goldberg said. “But what would it mean to quantify that?”

The study’s data will come from participants who are willing to have their anonymized biofeedback information uploaded to the cloud. From day one, researchers will be able to begin analyzing the results, but Goldberg says users’ confidentiality will be protected.

“Physiological data doesn’t really have much personally-identifying within it,” he said. So, showing the stress level of the city at, say, 9 a.m. — or during a cold snap or heat wave — shouldn’t be a problem. Most privacy concerns would arise with location data being aggregated and released to the public. “We want to take our time to make sure we get that absolutely right,” Goldberg said.

“Our goal is to do science at a scale and in a way that’s never been possible before. These technologies, worn computers, really do make that possible,” he said. “The longer-term goal is to understand the relationships between stress and chronic health conditions as well as stress and performance and productivity issues.”

Already, he says, with the few participants in a pilot phase aimed at refining the design and algorithms, “we’re pretty impressed by what we’ve been able to see so far. And, for those folks who are using our technologies, it becomes pretty clear how simply visualizing what you’re experiencing every day becomes immensely valuable to help you understand yourself better.”

'Supporting The Individual'

While Goldberg expressed excitement about the possible big-picture implications of the study’s results, he emphasized that the primary purpose of the technology is to benefit the individual. The integration with the app allows for very personalized visualizations. For instance, you can see how that beloved mellow song or dreaded dentist appointment affected your stress level.

“If we don’t do a good job of supporting the individual, then all of our grand ambitions, all the great questions we want to answer, won’t ever come to fruition,” Goldberg said.

The individual benefit of the technologies is compelling to Dr. Joseph Kvedar, vice president of Connected Health at Partners HealthCare. “Stress is one of those things that’s hard to measure, and having something like this to help us measure it…may help us combat stress and cope with it better,” he said.

Regarding the citywide analysis of stress, Kvedar said, “I’m not sure it’s going to be as compelling as it would versus an individual patient analysis."

Time To Recover

The results of the Boston Stress Study might influence workplace policies, Goldberg said.

The stress experienced on a morning commute can be equivalent to exercising, and, “If we thought we were out for a run, we would give ourselves an hour or two to recover,” he said. “We don’t give ourselves an hour or two to recover from our commute, from a difficult meeting at work, from medical appointments.”

“What if it turns out that commutes are one of the most stressful times of day for a city?” Goldberg added. “Will companies take more seriously the fact that their people are showing up already highly revved up?” Beginning the day stressed might impede productivity, which employers could take into consideration when scheduling meetings or setting work hours, he said.

Finding Participants

Rather than continue to manufacture a watch, Neumitra is working on incorporating the stress-measurement technology into lightweight “biomodules,” which could be incorporated into participants’ existing accessories, Goldberg said.

The watch loaned to me costs a hefty $1,500 — although its quality is on par with $20,000 medical equipment, Goldberg said — and would be out of reach for many people. Neumitra aims to make the biomodules more affordable.

The Boston Stress Study is still getting underway; participants are still being recruited and Neumitra is still refining the technologies and lining up funding.

Neumitra has partnered with a combination of commercial, nonprofit, and academic organizations to fund the study and recruit participants. The variety in partnerships is necessary to obtain a representative sample, Goldberg said.

“To do science at this scale, where every citizen both becomes a scientist and helps us to answer these questions as part of the organizations they belong to, this is really going to come from a mix of supporters,” he added.

Neumitra is currently working with clinical organizations in the area to find participants, and Mayor Marty Walsh has written a letter in support of the Boston Stress Study.

“The data from your study could provide us with vital insight into the various causes and effects of acute and chronic stressors in the daily lives and work of Boston residents,” Walsh wrote.

Lessons Learned

While I knew the subway commute was stressful, I didn’t perceive just how stressful until I used the watch. Not only that, but it taught me how strong an effect simply remembering a stressful event can have. The app can generate a line graph to illustrate your stress, and I could see clear spikes in the line that aligned with my recalling a stressful situation or embarrassing incident from earlier.

Stress triggers such pronounced physiological changes that it’s no wonder it takes a toll on the physical self as well as the psyche. From my time wearing the watch, I realized the power of being able to visualize the physiological response to stress.

On the other hand, I did find that watching my stress level rise second by second contributed to a heightened sense of anxiety. Yet, I also began to notice that consciously changing my thoughts allowed me to manage my physiological response.

I come away with a new note to self: When work piles up, or you have to run to catch the train, or you’re waiting in anticipation for a response to a text message, remember to make time for stress-relieving activities to allow yourself to recover from the strains of the day.

Readers, reactions?