Advertisement

Landmark Gene Discovery Cracks Open 'Black Box' Of Schizophrenia

Resume

One November day in her senior year of high school, Sydney accidentally broke the full-length mirror leaning up against the wall of her bedroom.

She felt a gust of superstitious dread: “Oh my God, I have to put this mirror together or I’m going to have bad luck.” Then, it escalated oddly into religious terror: “The devil’s coming to get me!”

Something inside her seemed to snap, she said. She sensed demons invading through the broken glass.

Not long afterward, President Obama spoke to Sydney inside her head: “OK, this is how the world is now,” he told her. “Everyone is so in love with each other, we can hear each other in our heads.”

The menacing voices of demons started to torment her, especially at night. She became convinced that she was going out with the pop star Justin Bieber, that he was chatting with her on her phone and sending her hidden messages in his Twitter feed. She thought he set up paparazzi in her backyard on Boston’s North Shore, that he was sending planes over her house to let her know he cared.

“Is this really happening?” She would ask the voices in her head. “Is this?” Yes, they told her. Yes.

What was really happening? How does a sunny girl who’d never had psychiatric problems before, who grew up loving dance and Disney princesses, a good student who was rich in family and friends, how does that girl suddenly lose her hold on reality?

Schizophrenia affects about 1 in every 100 people, and one thing is clear: Genetics plays a role. Sydney’s uncle had schizophrenia, and scientists have identified more than 100 genes that can raise the risk for it.

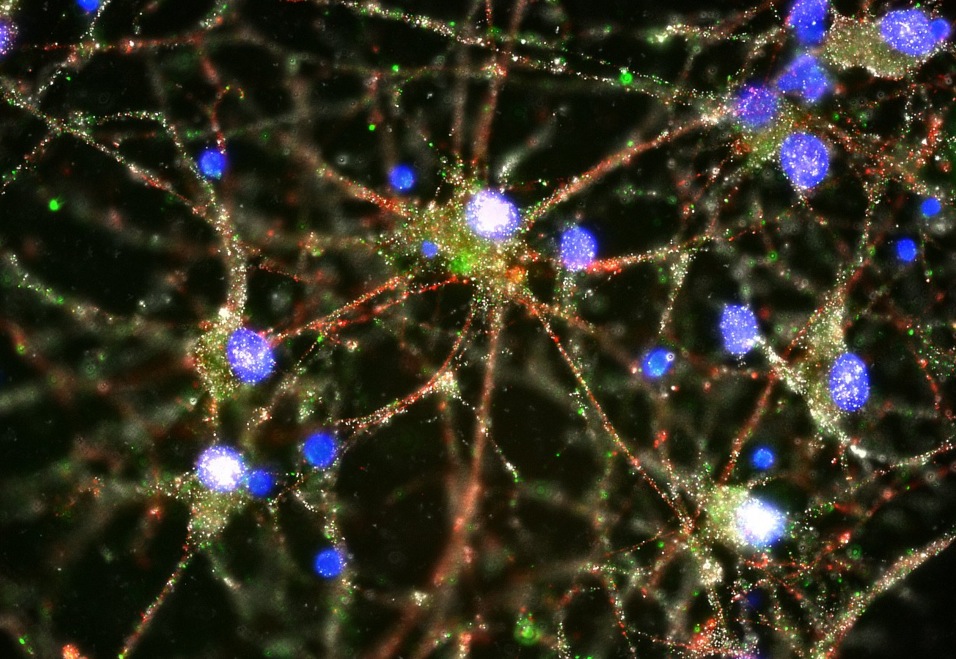

Now, researchers based at the Broad Institute in Cambridge and Harvard Medical School have pinpointed the gene that is the biggest risk factor for schizophrenia discovered so far, and figured out how it does its damage: It makes the brain prune away too many of the connections between neurons.

"[I]t may be like you have an over-energetic gardener who prunes back so much that the bushes die off..."

Bruce Cuthbert, of the National Institute of Mental Health

That finding, just published in the journal Nature, may also explain why schizophrenia tends to hit at such an odd age, in the late teens and early 20s. That pruning of connections is a normal process that ramps up during adolescence, but this genetic culprit may make it go overboard.

Pruning may sound bad, said Bruce Cuthbert, the acting director of the National Institute of Mental Health, but actually, it’s helpful: “It’s like clearing away the underbrush so your brain can function more efficiently.”

But, he said, “in people with this overactive version of the gene, it may be like you have an over-energetic gardener, who prunes back so much that the bushes die off because they don’t have enough branches.”

Cuthbert called the paper a “genetic breakthrough” and “a crucial turning point in the fight against mental illness.” Eric Lander, director of the Broad Institute, said it means we’re finally starting to understand what causes schizophrenia at the level of brain biology.

“For the first time," Lander said, "we’re opening up the black box and looking inside and seeing, how does the disease really arise? That makes this, in my opinion, perhaps the most important paper in schizophrenia since the disease itself was ever defined,” over a century ago.

This scientific excitement does not mean, however, that the findings will lead to new treatments for schizophrenia any time soon, Lander and others said. It takes years for such basic science to translate into treatments — if it ever does.

But the new paper does suggest some promising new targets for drug development, some already being worked on for other diseases, said Harvard Medical School's Steve McCarroll, who led the research team.

“You can tap into knowledge that’s already been generated, and that’s very important,” he said. “It’s much better than starting from nothing.”

Tens of thousands of people could arguably claim some credit for the Nature paper; it stems in part from a monumental global collaboration to gather DNA from more than 100,000 people in search of genetic clues to mental illnesses.

But first billing goes to a 29-year-old doctor-scientist-in-training, Aswin Sekar, who has a PhD in genetics and is now finishing up his M.D. degree at Harvard Medical School.

“He grabbed the problem by the horns and wouldn’t let go for three years,” said McCarroll, his supervisor. “He was just brave and fearless about it. He also didn’t care that everyone was telling him it was intractable. He just took that as an invitation to try new things.”

Did McCarroll worry that he might have let Sekar charge off down the wrong path?

“All the time.”

'Princesses Don’t Lose'

Right around the time that Aswin Sekar began to chase after that intractable problem, Sydney was being pulled against her will onto a journey of her own.

She heard voices of pop stars like Bieber and Ke$ha, and of men and women she didn’t know, voices so compelling they pushed all other thoughts out of her head.

“What color do you want your basket?” a male demon voice would ask her menacingly, referring to the expression “going to hell in a handbasket.”

And the romance with Bieber was stormy. Finally, after several months, she could bear the weirdness no longer and told a teacher about him. The school called home and said Sydney should be picked up, that she was hearing voices.

Sydney’s mother, Lori, a pharmacist, instantly recognized the resemblance between Sydney’s symptoms and her own brother’s, who had been institutionalized after sudden-onset schizophrenia in high school. She immediately started calling around to find treatment.

The first psychiatrist who saw Sydney said automatically, "'You have schizophrenia,' ” Lori said. Just as automatically, Sydney and Lori disliked her.

“It’s a big, scary word — schizophrenia,” Lori said. “And my beautiful ballerina — I just couldn’t even reconcile the two terms at all.”

The psychiatrist recommended an antipsychotic, but with Lori’s pharmacy knowledge, she did not want to start Sydney on such a heavy-duty medication. They decided to wait until they could be seen in a few weeks at CEDAR — the Center for Early Detection, Assessment and Response To Risk — a Boston clinic that specializes in helping young people with the earliest symptoms of psychosis.

“So we adopted Justin as our future son-in-law,” Lori said, referring to Bieber. And she resolved to do whatever it took to help her daughter: “If she was going down, I was going down with her. I was going to fight it.”

So was Sydney. When she could feel demons in her room with her, she would draw on her lifelong obsession with Disney princesses and tell herself: “I’m a princess. And princesses don’t lose.”

A Shape-Shifting Suspect

During Aswin Sekar’s early years in medical school at Harvard, it struck him how little we really know about the causes of disease — “pathogenesis,” in the lingo — particularly in psychiatry.

He set out to solve a riddle that had stymied gene researchers for years: signs that the immune system was involved in schizophrenia.

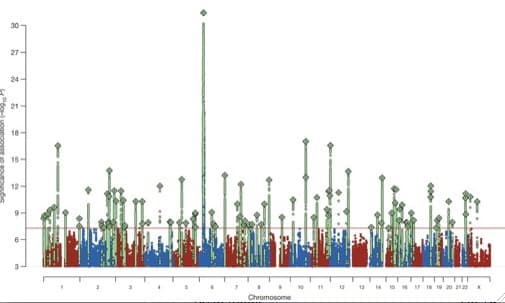

The biggest and most mysterious result in the genetics of schizophrenia was a powerful signal in a DNA area known to contain many immune-system molecules, research team leader McCarroll said.

“It was sort of like the ‘Who shot JFK’ mystery in genetics,” he said. “Everyone had a theory about it, but no one really knew.”

Some speculated that schizophrenia could be caused by an infection — perhaps even a parasite caught from cats — or that it could be an autoimmune disease.

Sekar decided to make a bet on a gene called C4. It was known to work in the body’s immune system to tag viruses for destruction; McCarroll described it as like an “Eat Me” sign. But it had no known role in the brain.

And the gene itself was hellishly complex, showing up in varying forms and structures in different people. Sekar knew he would need to develop new molecular methods to analyze it.

He did wet work at the lab bench, analyzing DNA in droplets so small you could fit 100 million of them in a test tube the size of your thumb.

He and his colleagues also tested nearly 700 samples from human brains (donated after death, of course) to check whether C4 was more active in samples from patients with schizophrenia than those without. In general, it was.

And he did big-data analysis looking at DNA from some 65,000 people’s genomes — their full sets of genes.

Cracking the initial problem of identifying C4 as a key gene, he said, was a bit like solving a murder case, with a couple of special challenges. Gene mapping had given him a ZIP code where his suspect could be found, but not the suspect’s address or name. And that ZIP code was in Manhattan — “very densely populated, with lots of buildings, and lots of them are skyscrapers.”

Oh, and by the way, the suspect could shape-shift.

“So in one genome, the suspect would be 5-foot-6 and in another genome the suspect is 5-foot-10. And in one genome the suspect appears to be acting by himself or herself and in another genome the suspect has a twin or maybe a triplet," Sekar said.

And once he had solved the whodunit, he still had to answer the how: What did C4 do to raise the risk of schizophrenia?

The gene findings pointed the way from the Broad Institute in Cambridge across the Charles River to Boston Children’s Hospital. There, neurobiologist Beth Stevens recently won a MacArthur genius award for her work on molecules like C4 in mouse brains.

She and Children’s immunologist Michael Carroll helped connect the final dots: They showed that in mice, C4 is crucial to pruning away connections between neurons. Young mice genetically engineered to lack C4 have much less pruning.

The C4 insights, Stevens said, have “paved a road ahead. We know what we need to do. We didn’t know that five years ago at all. It was this huge black box. And there are probably going to be other pathways and other genes, and more and more of these are going to kind of funnel in — maybe some of them are even related. But we have a plan. There was no plan.”

Seven or eight years ago, she said, if you had asked what her lab would focus on, “I don’t know if schizophrenia would have been top of the list, because it was so hard. Now, it’s a major goal of the lab.”

What they find may extend beyond schizophrenia. Cuthbert of the NIMH and others say the over-pruning process may contribute to other brain diseases, like psychotic bipolar disorder — it remains to be seen. But this is exactly the sort of work that the institute is trying to encourage, Cuthbert said, focusing less on broad behavioral patterns — like schizophrenia — and more on specific aspects of a disorder — like over-pruning.

So what exactly is the immune connection? Lander, the Broad Institute director, summarizes: C4 normally works in the body’s immune system to target germs for destruction, but it turns out that it “moonlights” in the brain.

“It has this second job, and its job in the brain is to mark synapses — connections between nerves — for destruction," Lander said. "Someday, you could imagine perhaps modulating, tweaking this process of synaptic pruning in somebody who was being affected with early schizophrenia. We’re very, very far from that, but knowing what’s actually the cause is just transformative.”

'Room To Move The Belief'

When Sydney first got to the CEDAR clinic in mid-2013, the staff was hugely impressed by “how pleasant she was, how socially engaged, just really sweet and bright and charming,” said clinical psychologist trainee Alison Thomas, who worked with her.

That was unusual, Thomas said; young people who come to CEDAR are often in great distress, confused and scared and unable to understand what’s happening.

“And Sydney’s like this little bright ray of sunshine,” she said. “And talking about serious things, but in this way that’s really personally connected.”

That social brilliance could partly mask the disorder, but it became ever more clear that Sydney was having serious symptoms.

“So we revised our thinking on what actually was happening a few months into working with her,” Thomas said.

The staff realized that Sydney fully believed her symptoms — demons, Bieber — were real, so she had moved past early warning signs to an actual psychotic process. But she had enough trust to accept treatment.

(Sydney gave Thomas permission to speak about her treatment, and was present as she did. Sydney hopes to help others who face similar psychiatric challenges, she said, but asked that her last name be omitted here for the sake of privacy.)

The CEDAR staff tries to be very sparing with anti-psychotic medications, which can have significant side effects, but as Sydney’s symptoms grew more severe, they prescribed one: Abilify.

But the demons only got worse. Sydney’s life took on elements from “The Exorcist.” Sometimes, she felt her bed was shaking, felt sure she was becoming possessed. She would run to Lori’s room and sleep with her.

“There was many a night I held her through the night,” Lori said, “and she was just shaking, terrified, awake, listening to these things. And I’m just whispering to her, ‘Sydney, it’s good, I got you, we’re good, remember it’s not real, remember, it’s not real.’ ”

Lori had to be constantly vigilant: Sydney took to sneaking out of the house in search of holy water in the middle of the night.

Once, she turned up across the river from their house, Lori said: “She was going to the cemetery to look for guidance from relatives there. And I didn’t even know she left the house. She had gone through a really, really bad part of the city.”

Sydney’s father and two brothers did their best to help, too. “My dad would say, ‘If there’s demons, you know I’d be out that door,’ ” Sydney said. But for her, the demons stayed put.

Her relationship with Justin Bieber marched on, and her family learned at CEDAR that they shouldn’t force reality checks on her love life.

“It would be like someone telling me I haven’t been married for 30 years,” Lori said. “I wouldn’t believe them. She wouldn’t believe us.”

When Sydney would point to a passing plane and say, “That’s Justin’s plane. He’s waving to us,” her mother and father would be out in the driveway, waving back.

Parents of young people with schizophrenia often have to redefine their roles, Thomas said.

“Your job is no longer to tell people what’s true and what’s not true," she said. "Your job now is just to make them feel safe, even if you’re doing crazy things like waving to planes, until we have room to move the belief.”

Often, she said, it takes medication to raise doubt about a belief, and then the psychological work to overturn it can begin.

Lori put her trust in the promise of medication, “that someday it’s just going to be gone.”

But for weeks, then months, as Sydney’s doses inched upward to near the maximum, the Abilify just wasn’t working. She switched from Abilify to the anti-psychotic drug risperidone, or Risperdal. More weeks passed.

Laptop Epiphany

Traditionally, stories of scientific advances include “Eureka moments,” named for the famous bathtub-inspired exclamation by the ancient Greek Archimedes.

But the climactic moments of the C4 story would not make for good theater. Film might be better: a sped-up montage of Aswin Sekar during the Christmas break of 2013-'14, sitting on his couch with his laptop for day after day after day, Googling to make up for his lack of computer science knowledge, with Pandora-guided holiday music playing in the background.

“I just could not set my laptop down,” he said. “I was just driven by this intense desire to know the answer as soon as possible.”

He had just gained access to the huge global dataset of tens of thousands of genomes, and thus to the statistical power to make sure that the C4 pattern he’d found in smaller cohorts was no mere fluke or fluctuation.

On the contrary, he found: “It seemed to be a more convincing pattern when we added these new data points.”

The data showed that a person’s structure of the C4 gene was not just linked to schizophrenia risk, but that it was “driving the risk of schizophrenia from that particular region of the genome," he said.

It was a “huge, screaming result,” said Sekar’s colleague and then-office-mate, graduate student Avery Davis, recalling the thrill that spread through the research team. “When you look at 60,000 people and you see that your hypotheses seem to be validated, that’s incredibly exciting."

So why doesn’t it sound more exciting? Why wasn’t Sekar jumping and dancing on his couch?

Maybe because in some areas of science, hypotheses — even seemingly confirmed ones — are not what they used to be. Asked whether the C4 story involved a Eureka moment, Lander, the Broad Institute director, quashed the whole idea:

"That’s what science really is: It isn’t the magic Eureka moment, it’s really nailing things down solidly.”

Eric Lander, of the Broad Institute

“You might think doing genomics is having a Eureka moment when you see an amazing correlation of X and Y — the genetic form of a gene and a risk of a disease,” he said. “In fact, it’s almost the opposite. Those correlations happen all the time. You see correlations like that and almost always, they’re wrong because something was funny about the data.”

With much of science now, he said, the key is disbelieving those putative correlations, resisting their “siren song,” and “pouring acid on them to see if they’ll go away. And finally, when you really, truly can’t make it go away and can’t explain it by anything else, and have looked at it six ways to Sunday and confirmed it all different ways, you actually believe it.”

Not at all cinematic, sitting on a finding for two years while you try to poke holes in it. But, Lander said, “That’s what science really is: It isn’t the magic Eureka moment, it’s really nailing things down solidly.”

By the way, if you’re wondering how the over-pruning of connections in the brain could give rise to the hallucinations that schizophrenia is best known for, the simple answer is, “We have no idea,” Lander said.

That’s beyond what anyone can explain right now, but it may be possible to devise drugs to dial down over-pruning in the coming years anyway.

“It may not be that we have to fully understand how these cellular events give rise to mental events in order to make a big difference in intervening someday,” he said.

'My Magic Medicine'

Somehow, through all her demons and delusions, Sydney went on with her life, attending community college and working part-time. Classroom time posed a particular challenge: “Indirects,” her sense that her fellow students’ mundane movements — a cough, a shifting of weight, a sip from a water bottle — were non-verbal communications directly to her. She felt compelled to answer them with her own movements — a blink, a tap of her foot — even while absorbing what the professor was saying.

The demons still tormented her, too. But as her risperidone dose increased each week, Sydney started to feel better.

“That was like my magic medicine,” she said. “Within weeks, I had less symptoms, I felt more comfortable in my skin.”

And then, one morning in January 2014, Justin Bieber was suddenly gone.

“I just woke up one day and I was like, ‘Mom, Justin Bieber’s not real.’ And she was like, ‘Oh my God.’ ”

For Alison Thomas of CEDAR, Bieber’s departure meant the risperidone was hitting the target.

“That’s how we knew that the medication was really working, we had found a good dose, is once Justin shifted — that belief,” she said.

Sydney was bereft at first. “I pictured myself being rich and famous, having a huge house and stuff,” she said. “So I cried. And then I just got over it: ‘Oh, I guess that happened.‘ “

She does get a bit embarrassed now, about the whole Bieber thing, laughing at the self she was back then. But she’s the kind of person who acknowledges what has happened and then moves on, she said.

And she has moved on with extraordinary success.

Still on risperidone — “I don’t ever want to stop taking my medicine,” she said — she has had no symptoms for almost two years now. She has been in a real relationship with an “awesome boyfriend” for nearly as long.

Now 20, Sydney works in a group home for young people with mental illness as a peer mentor, and in an after-school child care program. She’s doing so well that she has transferred from CEDAR to a local, less specialized care center.

Such a recovery may be possible for many people, Thomas said, but Sydney is unusual in how quickly it happened, and how well she managed to function throughout.

Schizophrenia involves not just delusions; it has “negative” symptoms as well — loss of motivation and emotional connection, trouble thinking and learning.

Medication can often help dispel the delusions, Thomas said, but those negative symptoms tend to be longer-lasting and tougher to overcome; they're often the root of poor functioning.

“So Sydney’s ability to stay engaged with the world around her and with people, and to really care about relationships” gave her a rare advantage, Thomas said. “Because that’s what really gives her motivation to keep going — because she cares about people.”

The Future

One percent of the population has schizophrenia and a recent study found that more broadly, up to 6 in 100 have experienced some sort of psychosis at some point. So how can more people with schizophrenia fare as well as Sydney? Or better yet, prevent the disorder altogether?

Researchers have been working for more than a dozen years on ways to predict whether young people’s initial milder symptoms of mental disturbance will actually develop into full-blown psychosis — and most importantly, whether it’s possible to head it off.

They include Larry Seidman of CEDAR and Harvard Medical School, who says research already finds significant progress on early intervention for psychosis.

Among symptomatic young people judged to be at high risk for psychosis, he said, studies show that with good treatment, only 1 in 10 goes on to develop full-blown psychosis, compared to 3 in 10 without it.

Treatment does not necessarily involve drugs; it can also include talk therapy and lifestyle measures — exercise, diet, sleep.

The C4 paper, Seidman said, is further cause for hope that treatment — and even prevention — will improve, because it shines new light on a biological pathway to the disorder.

“If we know this pathway, maybe there are very specific times in life when you might be able to intervene and alter that pathway,” he said. “Maybe there are other critical periods before adolescence when it’s more malleable. We don’t know.”

But it does seem possible, he said, that C4 gene testing could become one of the multiple measures used to assess a young person’s risk of progressing to full-blown psychosis. If that happens, he said — and it’s by no means certain, because the genetics is very complex — patients and families will need careful counseling to make sure the information is not misinterpreted.

Schizophrenia may come to resemble Cystic Fibrosis, said Cuthbert of the NIMH, in that genetic insights led to the development of a new targeted drug. True, the new drug only works for 4 percent of Cystic Fibrosis patients, he noted, but for that 4 percent, it makes a huge difference.

Research team leader McCarroll compares the prospects for schizophrenia to the sea change in cancer treatment over the last two decades. It was once a death sentence, he said, but “today, we’re surrounded by people who have been cured of cancer or who are managing cancer as a chronic illness very successfully.”

Still, it's a daunting prospect to develop a drug that tinkers with the immune system, our defender against infection. How directly might the C4 finding translate into better treatments?

It depends, McCarroll said. Some genes lead to good drug targets. Others do not.

“You could discover 20 genes underlying an illness that were not good drug targets and then find the 21st and it might be the place where you really can push on the system with a molecule,” he said. “That’s why you never give up.”