Advertisement

Researchers Use Big Data To Seek 'Unique Fingerprint' Of Long-Term Lyme Disease Symptoms

By Richard Knox

One of the hottest fashions in science these days is Big Data: the idea that revelations can be teased out from great masses of information. Now, some researchers are using the strategy to pry open the black box of Lyme disease.

Four decades after the tick-borne infection first came to light in the vicinity of Lyme, Connecticut, the small world of Lyme-focused researchers isn’t even close to understanding why the disease often seems to plague its victims with disabling immunologic and neurologic problems that can persist for years.

Dr. John Aucott thinks Big Data can change that. “We’re really embarking on a new stage -- a new era,” says Aucott, director of the year-old Lyme Disease Clinical Research Center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The first step is to show that chronic Lyme disease “is a real illness,” Aucott says. “Many people don’t believe it exists because there’s no objective underpinning.”

That is, there’s no diagnostic test -- a biological marker that’s present in people who suffer from chronic Lyme disease symptoms and absent in others. Consequently, the disorder widely called “chronic Lyme disease” is a grab bag of a diagnosis -- and probably not one singular disorder.

“Chronic Lyme usually refers to a very heterogeneous population with nonspecific ailments,” Aucott says. “Some may be related to Lyme, others to other tick-borne infections or illnesses we can’t define accurately.”

Aucott and his colleagues have just published some of the first Big Data-derived evidence in the journal mBio. They’ve found a set of activated genes in immune cells of patients newly infected with the Lyme disease bacterium, compared to similar people without Lyme.

"[The study results] may finally start cracking the mystery of why people fail therapy."

Dr. Harriet Kotsoris, Global Lyme Alliance

Intriguingly, some of these genes were still activated six months later, even among patients with verified Lyme disease who were successfully treated with antibiotics. Some of these genes overlapped with those activated in autoimmune diseases such as lupus and arthritis -- a hint that the Lyme disease bacterium can have a lasting effect on the immune system, a leading hypothesis that has lacked concrete evidence until now.

Dr. Harriet Kotsoris, chief science officer of the Global Lyme Alliance, says the results are provocative. “It may finally start cracking the mystery of why people fail therapy and give us an insight of the genetic makeup of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome,” she says. “And importantly, it may offer a diagnostic profile.”

One big problem is that patients who believe they have chronic Lyme disease can test negative for antibodies for the infection. That doesn’t mean they weren’t infected, but it does leave them in diagnostic limbo.

To uncover the gene-expression pattern, Aucott and his colleagues had to do 73 million gene sequence “reads” for each of the study subjects -- 29 with Lyme disease and 13 controls. That’s the Big Data. They’ve since sampled the immune cells of 175 patients.

Next they’ll determine what proteins the turned-on genes make, which immune cells have the activated genes, and “the whole business” of what’s unique about Lyme disease patients, Aucott says.

“Maybe there’s a unique fingerprint,” Aucott says -- a molecular signature that distinguishes patients who have symptoms such as fatigue, joint and muscle pain, and cognitive and sensory problems following initial antibiotic treatment of acute Lyme infection.

That would be a big deal. Perhaps one in five Lyme disease patients goes on to develop long-term symptoms. Since federal officials estimate around 300,000 Americans get Lyme every year -- nearly all of them in the Northeast and upper Midwest -- that could mean 60,000 of them may develop chronic symptoms. And those numbers accumulate year-upon-year.

Desperation And Despair

This situation frustrates doctors confronted with patients suffering post-Lyme symptoms. And it drives patients to desperation and despair. Heated controversies over what chronic Lyme is and how to treat it has attracted fringe-y practitioners and made many mainstream physicians wary.

“My family doctor said, ‘I can’t help you,’ ” says Sherrill Franklin, a 63-year-old Pennsylvania woman who says she’s suffered from Lyme-related symptoms on and off for 30 years. “Doctors are scared to touch it. They’re afraid they’re going to lose their licenses.”

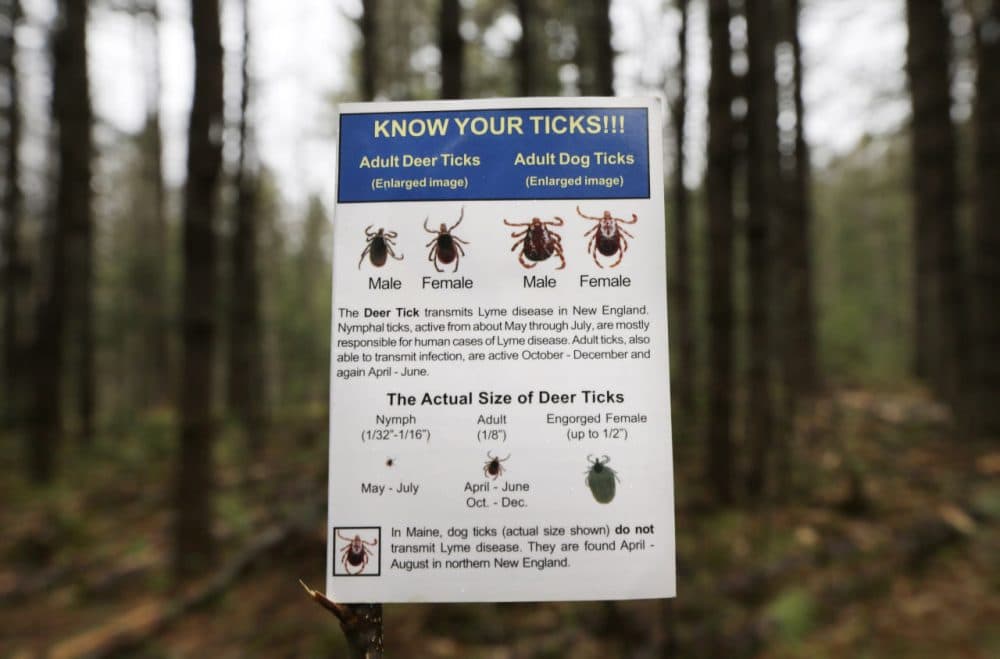

There’s no doubt what caused Franklin’s initial illness back in 1986. The bite of a deer tick infected her with Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium which causes Lyme disease. (Mayo Clinic researchers recently identified a new tick-borne bacterial species that can also cause Lyme, though it produces slightly different initial symptoms.)

Soon after her tick bite, Franklin developed a sore throat and big bull’s eye rash followed by painful joints -- typical hallmarks of Lyme, although they don’t appear in every case.

Two courses of antibiotics over the following two years made Franklin’s symptoms go away. Then in 2008 she got another tick bite. No one can say what caused the subsequent dizziness, vision problems, ringing in the ears, weight loss, muscle pain and extreme fatigue she suffered after that. She’s still not fully recovered.

It could have been reinfection with the Lyme bacterium. Or perhaps not; a blood test suggested it could have been anaplasmosis, another disease carried by ticks. Or maybe some of the Lyme bacteria evaded her long-ago antibiotic treatment and persist in her body somewhere -- a current hypothesis that so far lacks evidence. Or possibly it’s just the way Franklin’s immune system reacted to the tick-borne infection(s).

Repeated courses of antibiotics, by mouth and IV, appear to have helped Franklin. “I’m better -- like 85 percent of normal,” she says. “I usually can’t stay awake past 8:30 and I used to stay up ‘til midnight. I used to ice skate three times a week. Now I can’t do it at all. My ears still ring sometimes and I still have muscle aches. So something is still there. It could be permanent.”

Franklin’s story is typical of tens if not hundreds of thousands of Americans who have troublesome ailments following apparent Lyme disease infections.

'We Don't Have To Wait'

She also represents a different Big Data approach to the problem of just what ails these people.

Franklin is among 3,000 or so people who have agreed to submit detailed data on their illness -- their illness history, treatments, symptoms, daily functioning, test results and other relevant data every three months going forward. The project also aims to upload patients’ test results, genetic profiles, if available, and input from their physicians.

The newly launched project is called MyLymeData, sponsored by a Web-based group called LymeDisease.org, which is headed by Lorraine Johnson, a Lyme disease patient herself.

“It’s time for us to turn to the tools of Big Data to try to solve the problems that have existed in Lyme for a long time,” Johnson says. “We have tools available we didn’t have 15 years ago. There hasn’t been an NIH study on the treatment of Lyme in 15 years. But we don’t have to wait.”

Johnson hopes to enroll thousands more patients. The aim is to identify patterns -- such as what distinguishes patients who get well from those who don’t, which treatments work and which don’t, and whether having other infections or disorders affects their symptoms.

Johnson talked about the project at a Feb. 13 session of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., in which Aucott also participated.

Those in the field welcome the patient-generated Big Data project, says Kotsoris of the Global Lyme Alliance. But some point out the pitfalls in deriving self-reported data from self-selected patients -- a method that can’t hope to match carefully vetted information from well-done conventional clinical studies.

Kotsoris agrees that “there will be a lot of data that will not be valid.” But she says if enough patients participate and the data are properly analyzed, large numbers of data points can wash out spurious leads.

“We can only hope that data analysts will find certain trends or patterns that give researchers clues,” Kotsoris says. “If you have significant numbers reporting the same thing, then you may say, ‘Aha! Let’s look at this, there may be something interesting here.’ ”

In general, she says, research in Lyme disease is "woefully under-funded" by the federal government. And more research is better than less.