Advertisement

Hits Affecting The Head — Even Ones Without Concussions — Cause CTE, BU Study Finds

Resume

Researchers say a new study provides the "best evidence to date" that hits to the head — even ones that do not lead to concussions — cause CTE, the degenerative brain disease found in contact-sport athletes, members of the military and others who suffer repetitive head trauma.

The Boston University study published Thursday in the neurology journal "Brain" emphasizes that focusing on the link between concussions and CTE is misguided, as the results of the study show preventing all hits to the head is the key to preventing CTE.

The study also found that CTE can begin earlier than previously thought.

CTE In Brains Without Concussions

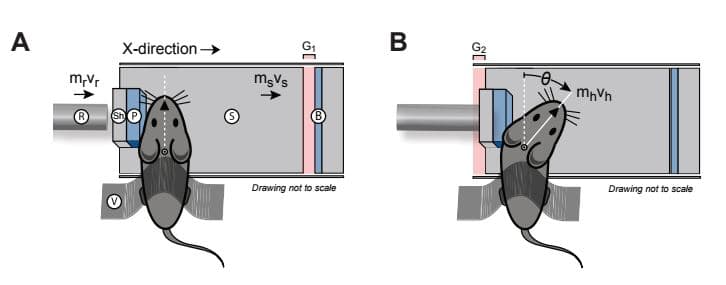

BU's Lee Goldstein said the goal of the study was to understand how impacts to the head trigger CTE. His team wanted to create a device that would allow the head to move in exactly the same way when subjected to a hit like the ones athletes experience.

"So what we have here is a device that is able to impart to a mouse pretty much what you would see with a flying tackle from a linebacker to an opposing quarterback to the left side of the head," Goldstein said.

In an earlier study, Boston University researchers determined head motion — and not the blast wave — is the cause of CTE in people, like military service members, who are exposed to blasts from improvised explosive devices. So, while researchers have suspected hits impacting the head may be responsible for CTE, Goldstein, who led the new study, says his team's research has provided the first conclusive evidence.

Goldstein is an associate professor of many disciplines at BU: psychiatry, neurology, ophthalmology, pathology, laboratory medicine, and biomedical engineering. His group has been working on this project for seven years.

He said one engineering challenge was to mirror the head motion experienced by people in the mice — and not to deform the skulls of mice in the experiment.

"That’s not what we want to look at. We want to look at sports-related injuries that are considered much milder," Goldstein said.

Researchers used an air cannon to propel a small object Goldstein calls “a slug” against a mouse helmet to make the mouse's head move in the same way as in a football helmet-to-helmet hit.

"[The helmet] has as a hard shell and an inner foam pad, and the head is going to be right here, resting against here, just like an athlete in the moments before receiving the flying tackle," Goldstein says, pointing to the instrument.

"That's it," Goldstein says as the slug hits the helmet. "So this is like a right hook or a flying tackle. Every time we do this in this type of experiment, we always get CTE pathology, and we always get some degree of concussion. And it's the animal equivalent of concussion. And even rarely, we get post-traumatic seizures, just like we saw with Tom Savage on the NFL."

Houston Texans quarterback Tom Savage appeared to suffer a seizure after being tackled last December.

The BU team had already conducted hundreds of experiments in which mice were subjected to a blast to replicate the shock wave experienced by service members with head injuries following exposure to improvised explosive devices. In both the previous experiments and the ones conducted in this study, the mice's heads moved in the exact same way.

Goldstein added that the mice in the experiments mimicking service members' experiences, researchers never found the mice suffered concussions.

"Head's moving exactly the same, and they both get CTE," Goldstein said. "And so what that tells us right off the bat is that concussion cannot be associated with CTE."

Starting Younger, Playing Longer Increases Risk

In the mice wearing helmets hit by the slug, Goldstein's team also found something else.

"There's no correlation of the degree of concussion with the CTE," Goldstein said. "Our data suggest that the human CTE correlates better with total exposure and the earlier exposure. Those kids who play Pop Warner when they start young and play longer are at greater risk than those who start later and play shorter."

"I'm not sure about the part starting younger," said Julian Bailes, the chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee for Pop Warner Football. "I think that's not proven and subject to a lot of debate."

But, Bailes did say he believes "that CTE is related to years of exposure, but primarily exposure at the higher levels of play — probably starting in high school, where there are 600 to 800 hits a year, and in college, where there are even more, and continuing on into professional."

"We see [CTE] even after one exposure to the impact, and it not only persists, but it will progress. It spreads through the brain. It will spread as you age."

Lee Goldstein

One of the authors of the study, BU Professor of Neurology and Pathology Ann McKee, said the results confirmed a suspicion raised by the team's analysis of human brains.

"We know from our own pathologic work that about 20 percent of the brain donors with CTE never had a concussion," she said, "so there's always been a bit of a disconnect between concussion and the development of CTE."

Goldstein's team also found CTE in mice with few hits to the head.

"We see it even after one exposure to the impact, and it not only persists, but it will progress," Goldstein said. "It spreads through the brain. It will spread as you age."

Among the policy implications, Goldstein said, is that concussions should not be the only focus in injury prevention.

"The analogy I like to give on this is, while smoking can lead to a hacking cough and lung cancer, we shouldn't be doing our lung cancer screening by looking for a hacking cough," he said. "They're different mechanisms. And in fact, that's what we see here: the concussion is actually a different mechanism from the mechanisms that lead to CTE. We can completely dissociate them. We can have CTE with or without a concussion. It's somewhat irrelevant."

Goldstein said preventing hits will prevent CTE.

"For example, in soccer, maybe we stick to the foot game up until a certain age before we get into a head game," Goldstein opined. "Maybe for football, we play the game differently up until a certain age, and then people can make a decision when they're more mature, or the brain is more mature, about how they're going to play it as young adults."

Building on the science of this study, the Concussion Legacy Foundation is launching a campaign to get children under 14 to play flag football.

"It will make a world of difference for your child's experience in playing the game of football if you actually delay the onset of tackling ... until their brain has had a chance to develop and until their body is really ready for tackle."

Chris Nowinski

Chris Nowinski, the chairman of the foundation and one of the authors of the study, said the campaign aims to educate parents, including asking them to consider not enrolling their children in tackle football until age 14.

"It will make a world of difference for your child's experience in playing the game of football if you actually delay the onset of tackling, which now will involve hundreds of hits to the head, until their brain has had a chance to develop and until their body is really ready for tackle," Nowinski said. "And that goes against the recommendations that you're getting from the NFL and the youth football industry."

The NFL did not respond to a request for comment.

Nowinski's group is also recommending no heading in soccer until age 14 and supports eliminating checking in boys' ice hockey until 15.

That's not a recommendation that former Dartmouth hockey player Mike Richardson, a Hingham hockey dad and president of Hingham Youth Hockey, agrees with.

"I think they should go the other way and allow more body contact at a younger age and teach kids how to protect themselves, how to take a hit, give a hit, not put themselves in a bad situation," Richardson said. "And kids are relatively the same size at 10 and 11. Once you get to 14, 15 and puberty hits, the size disparity is much wider at that age level. There could be more opportunities for no-check leagues for kids that don't want that contact."

"I think they should go the other way and allow more body contact at a younger age and teach kids how to protect themselves, how to take a hit, give a hit ..."

Mike Richardson

This year, Nicole de Moulpied, a Dunstable hockey mom, started a no-check hockey program after her son suffered a concussion, though not from hockey. De Moulpied said the BU study is probably a game-changer.

"And in terms of hockey, it might influence the rule-makers to increase the age when checking is introduced," De Moulpied said. "That sounds like a compelling reason to possibly make some changes. So it'll be interesting to see if this actually spurs some movement."

This segment aired on January 19, 2018.