Advertisement

Ibogaine: One Man's Journey To Mexico For Psychedelic Addiction Treatment

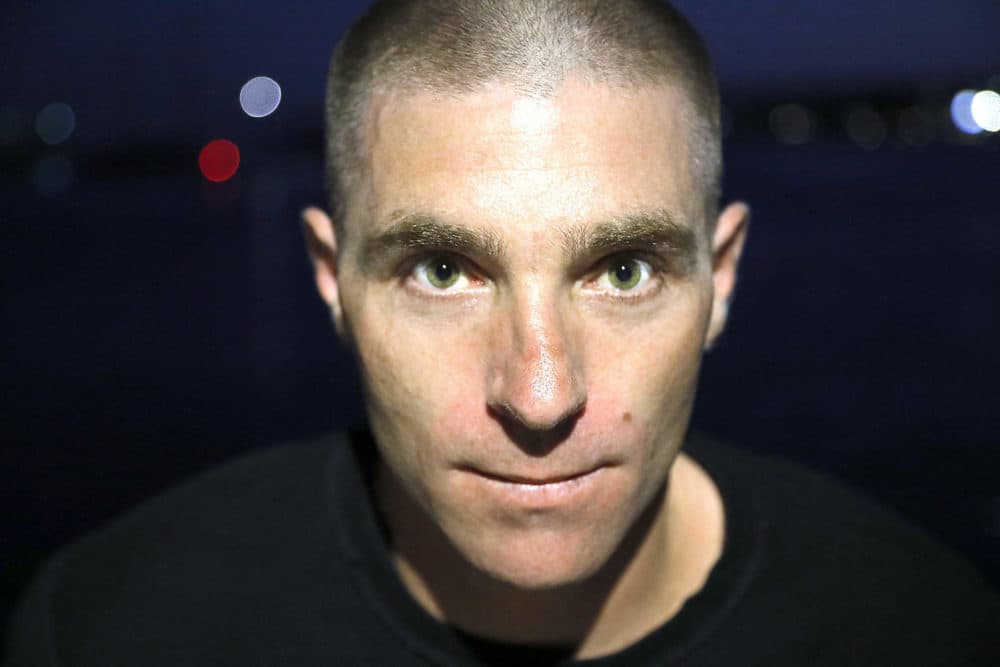

By the time Dustin Dextraze decides to travel outside of the United States to get psychedelic addiction treatment, he's desperate.

"I tried to overdose about a week ago," he says. "And I just woke up like five hours later and the needle was in my arm, and I just woke up and was like, 'well, didn't die, so ... Now what?' "

It's taken about three years for Dextraze to get to this point. He started using prescription painkillers recreationally, then switched to heroin because it was less expensive and easier to get. He lost his car, his job. He left his wife, his three kids.

At 36 years old he's shuffling between staying with his father in Massachusetts and his mother in New Hampshire. Every day he focuses on panhandling to get money to buy drugs so he won't be sick from withdrawing from opioid use.

Walking the streets of Dover, New Hampshire, in July, Dextraze is so dope sick he can barely focus.

"I'm gonna be alright. I have to be until I go find someone to find something for me," he says, often groaning, chain-smoking cigarettes, and frequently stopping strangers to ask for money or drugs.

"It's not like Massachusetts where I can just walk down the street and get it from anybody," Dextraze says. "Five bucks and I wouldn't be sick."

'My Whole Life Is Riding On This'

Dextraze says he hates this cycle of panhandling to get drugs. For years, he's tried to quit. He's been to several detoxes and rehabs, taken addiction medications, attended 12-step meetings — but nothing has worked. His drug use has landed him in the hospital with a severe blood infection, and he now has hepatitis C. He's been jailed for possession.

"The day I got out of jail I used," Dextraze says. "It's just a constant cycle, and it becomes such a vicious cycle, you can't get out of it."

What's giving Dextraze some hope that he can break the cycle, though, is an alternative psychedelic treatment called ibogaine. But it's illegal in the U.S.

Ibogaine is a substance from the iboga plant that's primarily found in Africa. It's believed to be used in coming-of-age ceremonies by the Bwiti religion.

For decades people have reported it eliminates withdrawal symptoms and cravings associated with various drugs. And many say it's most effective for opioid users.

"I've tried everything they've offered me to try, and this is the last thing that I know of is the ibogaine," Dextraze says. "My whole life is riding on this ibogaine."

A Drug Mired In Controversy

Claims about ibogaine have been controversial, and the subject of several studies.

Dr. Kenneth Alper, an associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at NYU, has studied the psychedelic drug and its history. He found ibogaine was first tested in the U.S. in the 1950s, but it became better known in '60s when scientist Howard Lotsof claimed ibogaine eliminated his heroin withdrawals — so he began treating others with it. Less than 10 years later, ibogaine was declared a Schedule 1 drug in the U.S. because of its psychoactive effects. The World Health Assembly classified ibogaine as a "substance likely to cause dependency or endanger human health."

But still, ibogaine advocates have pushed for more testing in the U.S. amid reports in other countries that it was effective in addressing addiction to heroin and cocaine. At one point in the '90s, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved testing it, but that was never completed — reportedly because of health risks.

"[Ibogaine is] apparently telling us something that is pertinent to either drug discovery or understanding the neurobiology of opiate dependence," NYU's Alper says. "The fact that we cannot readily explain it means that it's probably going to teach us something that we do not already know about addiction."

But many researchers are reluctant to do more research because of the reported risks. One of Alper's studies found that 19 people died after using ibogaine between 1990 and 2008. Most of the deaths were attributed to heart problems. Some researchers say that's largely because of ibogaine's underground status, which means patients are not properly screened and medical professionals are not administering it.

"People think there is going to be a magic pill that's going to erase addiction, and that's just not reality. What they should not be desperate for is a quick fix."

Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Bertha Madras

Dr. Martin Polanco, the founder of an addiction treatment center in northern Mexico, has studied ibogaine and says the drug is safe if it is properly administered.

"Ibogaine has known cardiac risks in that it reduces heart rate," Polanco says. "When combined with other medications, it can cause arrhythmias. It's important to be under continuous cardiac supervision while on the medication."

But it is also risky to find a reputable medical provider of ibogaine outside the U.S., where dozens of clinics are operating. In Mexico, the psychedelic treatment is not illegal — but it's not exactly sanctioned medicine, either.

Polanco used to run an ibogaine clinic in Mexico but moved it to the Bahamas because of concerns about the safety of his patients and staff there.

Polanco warns people should research their provider, saying "the quality of treatment and medical oversight can vary from one clinic to another."

To Mexico, To 'Take This Chance'

Dextraze believes he's found a reputable provider through someone he knows from Massachusetts who works at a clinic in Mexico. Friends offer to pay the $5,000 for a week of treatment, and his mother buys his plane ticket. He says any potential risks don't scare him; he says his drug use has already put him in a dangerous place.

"I was ready to die anyways," he says. "So I'd rather take this chance and be able to live a normal life than not take this chance and die a horrible death on dope."

Before arriving at the clinic, he landed in San Diego and immediately left to look for drugs. He went missing for a few days, but then got in touch with the clinic. They came to bring him to treatment.

For the first few days at the Experience Ibogaine Treatment Center in Mexico, Dextraze goes through medical tests of his heart and liver and takes short-acting opioids so he doesn't get sick. He's advised to rest and do light exercise while learning about what to expect from the treatment.

The clinic is actually two well-appointed homes next door to each other that the clinic owners rent in a gated residential community. The homes are private, perched high on a hill just south of Tijuana, with views of the Pacific Ocean. One home has treatment rooms and staff offices. The other is where patients stay for about a week after taking ibogaine. On the grounds are a sauna, a hot tub and hammocks. A chef prepares meals and clinic staffers oversee the patients.

Once Dextraze is medically cleared, he can take ibogaine. It will be given at night, when the short-acting opiates wear off and Dextraze starts to go into withdrawal. The clinic staff have been warned Dextraze that he may see visions that aren't pleasant. Still, Dextraze is eager.

"I was a little nervous, but I'm just going to remind myself that this is in my head and none of it's real — nothing can hurt me," Dextraze says.

The day Dextraze is due to take ibogaine, he fasts after breakfast. Two nurses and a doctor monitor Dextraze and the other patient there at the time. Aeden Smith-Ahearn, the treatment coordinator, is also on hand to help.

"It's absolutely crucial to have medical staff here, because it is a dangerous substance," Smith-Ahearn says. "It's cardiotoxic."

A Massachusetts native, Smith-Ahearn knew Dextraze before he came to Mexico. Six years ago, Smith-Ahearn came to Mexico to get ibogaine treatment for his own addiction to opioids. He's been an ibogaine enthusiast ever since.

Smith-Ahearn estimates his clinic has treated more than 1,000 people in the past five years, and that more than 95 percent of them are from the U.S. He says most patients seek ibogaine after several tries at conventional treatment -- when they reach a point where they believe ibogaine is less risky than continuing to use drugs.

"Just having gone through the hell that most of these people have gone through — and because of how the American health system is set up — I just feel that there is not a lot of hope for people over there," Smith-Ahearn says.

Dr. Paul Castillo, who will administer the ibogaine, also works in a hospital emergency room in Mexico. He became a supporter of ibogaine after a friend who owned another clinic asked him to help monitor patients.

"When they arrive, [there are] like clouds in their eyes. After [ibogaine], shining eyes, smiling," Castillo says. "They're alive, basically."

Castillo follows treatment guidelines from the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance, a Canadian nonprofit that developed the guidelines in 2015 and updated them last year. They recommend continuously monitoring patients — especially their hearts. The clinic says it gets the ibogaine from a lab it trusts in Africa.

Right before he gives Dextraze the medication, Castillo hooks him up to a heart monitor and puts in an IV. He checks Dextraze's blood pressure and temperature. Then he gives him a capsule containing a small "test dose" to make sure Dextraze doesn't have an adverse reaction. After about an hour, he administers a full dose based on Dextraze's weight and drug history.

The treatment is partly spiritual, Castillo says, so he and the nurses speak softly, dim the lights, and put on soft flute music. Smith-Ahearn burns sage in the treatment rooms, he says, for cleansing. Dextraze lies on a double bed, hooked up to the medical monitors with a sleeping mask over his eyes.

"I feel a little warm," he says. "I feel something, but I'm just relaxed. Normally, in withdrawal, I wouldn't be this relaxed."

For about the next 10 hours Dextraze lies in the darkened room, mostly quiet. The medical staffers stay with him most of the night. The next morning Dextraze describes sometimes feeling as if his body was vibrating. He also says he saw visions, like someone was showing him photos of the negative things he has done.

"I saw my kids when I left them," Dextraze says, "and I knew that they were sad and afraid that I wasn't coming back, so I kept saying, 'I didn't really leave them.'

"It also showed me other embarrassing things I've done ... I don’t want to go into detail about a lot of it. But once I said, 'OK, I did those things,' it got better. At first it seemed like it was not the greatest experience, because it wasn’t — but it was exactly what I needed."

And Dextraze says for the first time in three years, he doesn't have any withdrawal symptoms.

"Even when I was in detox I would feel some withdrawal," he says. "But now, nothing, absolutely nothing."

The Psychedelic Experience

It's not clear exactly how ibogaine eliminates withdrawal, but most studies describe it as affecting the brain's receptors in a way that resets them back to their pre-addictive state.

Dr. Alan Davis, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University, has been a leader in studying psychedelic treatments. One of Davis' research papers surveyed 88 ibogaine patients, and 80 percent reported fewer or less intense withdrawal symptoms.

"There seems to be, especially for people who have an opioid use disorder, some critical piece that often gets in the way of success in treatments that are currently available in the United States," Davis says. "You know, most people drop out of detox or treatment because of their withdrawal symptoms or cravings.

"I wouldn't say this is a magic bullet. I think there are a lot of unknowns about why it works for some people."

Davis' research also found that many of those who reported success from ibogaine attributed it in large part to the psychedelic experience. Essentially, they said they benefited as much from the psychedelic trip as they did from the removal of the physical withdrawal symptoms.

Davis is studying this in other psychedelics, too — namely the substance 5 MEO-DMT, which is said to cause an intense mystical experience. Many ibogaine clinics offer other psychedelics, like 5 MEO-DMT, as complementary treatments.

Dextraze's psychedelic experience under ibogaine was considered somewhat minimal. So three days after taking the ibogaine, the clinic gives him 5 MEO-DMT.

A Short But Intense Trip

Smith-Ahearn puts a sand-like substance into a small glass pipe and lights it.

"It's life-changing," Smith-Ahearn says, "and what you're about to see with Dustin, it's mind-blowing."

Dextraze inhales from the glass pipe, holds it in for a few seconds, and lays back on a bed in the treatment room. Almost immediately, he starts intensely tripping.

He's smiling and yells out while staring at the ceiling, addressing people or things unseen: "Yeah dude ... I knew it, man. ... I don't have to hang onto anything anymore. ... I don't ever want to come back from this. ... Please don't ever go away."

After about 20 minutes Dextraze becomes coherent again. When he's able to describe the experience, he calls it one of the most positive, intense things he's ever been through.

"I was surrounded by love," Dextraze says. "I just feel completely at peace. It's like I understand the world, and I know now that I will never be a slave to drugs again."

Psychedelics are increasingly being used and tested for a variety of disorders such as PTSD and depression.

Another addiction clinic in Mexico, the Baja Ibogaine Center, offers the anesthetic ketamine to patients struggling with depression. The center's owner, Jose Cerva, says these medications should be further researched and might help with the opioid epidemic.

"I don’t know why it is this way," Cerva says. "The U.S. has the funds to start doing studies on ibogaine and other psychedelics. America has to be more open about it. There is a lot of potential, and the U.S. addiction treatment system is obviously failing."

Will Ibogaine Work In The Long-Term?

The long-term success rate of ibogaine is not known. Both clinics in Mexico say no one in their care has died from taking ibogaine, and both estimate about 40 percent of their patients stay off drugs long-term.

But the clinics acknowledge that information comes from those patients they stay in contact with. They add that the key to success for patients is ongoing support, and many times that means conventional treatment after they leave the clinic.

Davis, from John Hopkins, says this is where his research found a significant problem.

"Largely absent [in his ibogaine study] was any followup aftercare," Davis says. "So people who return home may not have the support they need to continue making changes in their lives."

"Now you have to work at it. ... You can't just leave here and expect that that part of your life is magically over."

Aeden Smith-Ahearn, treatment coordinator, to Dextraze

For Dextraze, the clinic staff works with him on an aftercare plan. They review several options: inpatient treatment, outpatient counseling, different types of social support meetings like AA, Smart Recovery or Refuge Recovery.

Smith-Ahearn tells Dextraze the most successful patients are the ones who seek additional support.

"Now you have to work at it," he says. "You definitely need more support. You can't just leave here and expect that that part of your life is magically over."

He and Dextraze look online and call treatment providers. Some won't take public insurance, and others have long wait lists. With Dextraze's flight leaving in a few days, the pair agree that when Dextraze returns to New Hampshire, he'll start with counseling and join support groups while looking into how long it might take to get into inpatient treatment.

Back Home And 'Not Trying To Escape Life Anymore'

A few days after returning to his mother's home in New Hampshire, Dextraze maintains ibogaine is a miracle.

"Not just 100 percent — I'm 110 percent. Like I am totally OK with myself. I'm not trying to escape life anymore. I've never felt this way in my whole entire life," Dextraze says. "It's not just [that] it gets you off the heroin, it's like, it hits the reset button — that's the only way to really explain it. It's like a new brain."

Dextraze is reuniting with his children, he got a part-time job, and he's going to counseling and attending support meetings. At this point, he feels he needs only minimal support.

"I think now it's to help other people — that's why I'm going to the meetings," he says. "And by helping them, I'm helping myself, because we are all one."

Dextraze also has family support. His mother, Pamela Stack, gets emotional when she says she has her son back.

"Look at his eyes, you know, it's just a big difference. He's not trying to steal something. You know, you don't have to watch him, that he's going to walk out of here with whatever he feels like, because he has done that many times," Stack says, wiping away tears. "There is still a trust issue. I just don't know if this is going to last."

Several studies suggest that ibogaine stays in the body for weeks. NYU professor and psychiatrist Alper says that his research over the course of 20 years suggests that after taking it, people appear able to refrain from drugs — at least at first.

"My best representative guess would be that it's usually in the range of about one to three months of diminished drug use," Alper says. "People need to use this opportunity to restructure their lives."

Alper says ibogaine's success rate also depends on properly screening those who take it. He says before someone is given ibogaine, they should not be taking other drugs and should not have certain co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

'People Think There Is Going To Be A Magic Pill'

That was a problem for Kathleen Cochran, who sent her daughter to Mexico for ibogaine treatment three years ago.

"I understand that it works for some people, but it ended up not working for my daughter," Cochran says. She says the psychoactive experience caused her daughter to have visions of unresolved childhood trauma, and there was no support to help deal with it. Her 27-year-old daughter is now stable on methadone.

Cochran says people should be wary of alternative medicine in foreign countries.

"My advice would be to wait until ibogaine is legal in the U.S. and surround yourself with experts who are able to deal with the aftermath of the trauma," she says.

Ibogaine opponents often point to stories like Cochran's as a reason why people shouldn't use psychedelics.

Harvard Medical School professor Dr. Bertha Madras, a member of the White House Opioid Commission, says there haven't been solid scientific studies on these substances — especially on how they affect those with mental health conditions, which is a large percentage of those with addiction. Madras says she understands that the opioid epidemic has made many people feel desperate, but, she says, there is already treatment in this country that's backed by strong scientific research.

"People think there is going to be a magic pill that's going to erase addiction, and that's just not reality," Madras says. "What they should not be desperate for is a quick fix. High-quality treatment centers do exist in this country, and that's where they should be flocking to, as opposed to places that have undocumented data and anecdotal evidence. I just think it's fraught with hazard."

Ibogaine proponents acknowledge the risks and say that's why the U.S. should do more research.

Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, says the nonprofit organization published research last year showing that ibogaine significantly reduced drug use — in some cases by as long as 12 months.

"The risk of untreated addiction is terrible as well, more terrible than the risks of ibogaine administered under medical supervision," Doblin says.

Doblin wrote to the White House Opioid Commission last year asking for more research and pointing out that three states brought forward bills seeking to establish pilot ibogaine programs. None of those bills has passed though.

The pharmaceutical company Savant HWP has received a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to do human testing of a substance called 18 MC, which is said to mimic the withdrawal-eliminating properties of ibogaine without the psychoactive effects. Some researchers estimate it will likely be eight to 10 years before ibogaine might be available in this country.

Dustin Dextraze says he's glad he didn't have to wait.

"Remember that person I was when we first met in New Hampshire?" he asks. "All I cared about was finding drugs. I could make the choice to go out and use right now, but I don't want to. I don't need to. I'm where I want to be right now."

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave the incorrect year for when the Global Ibogaine Therapy Alliance first developed its treatment guidelines. We regret the error.