Advertisement

CRISPRed Food: How Gene Editing Is Expected To Change Our Crops — And Supermarket Shelves

Resume

This is part of our series "Lab to Table: The Future of Our Food." Stories are airing every Monday until Dec. 17. In the spring, the series will continue with another week of stories.

Delicate green shoots float in glasses of water, the pale tendrils of their roots coiling beneath the surface. Seedlings sprout from clumps of peat the size of a child's fist. Foot-high stalks rise from quart pots of soil under bright grow lights.

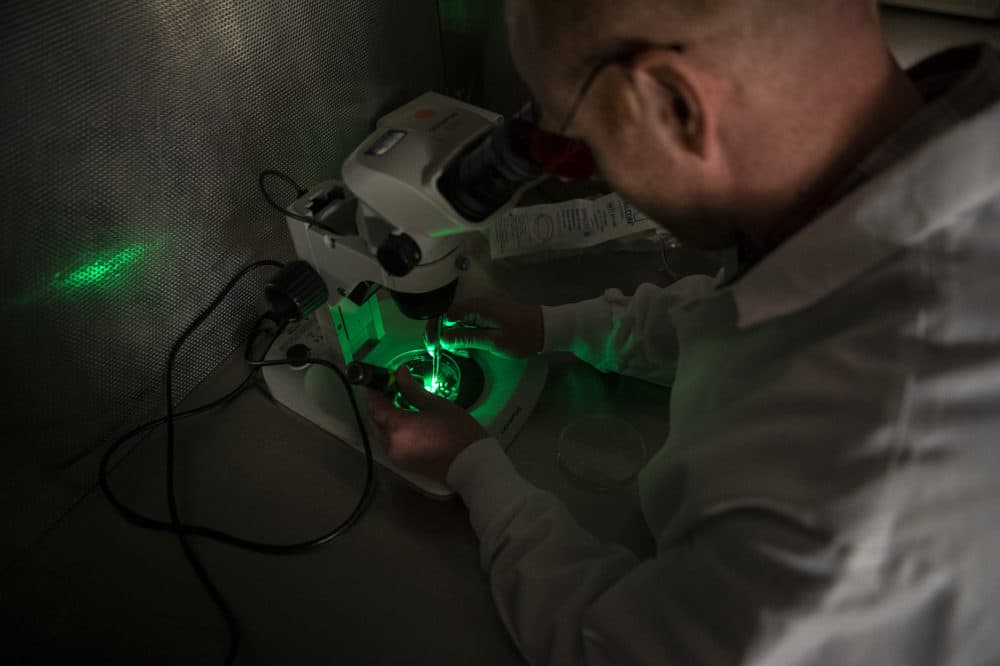

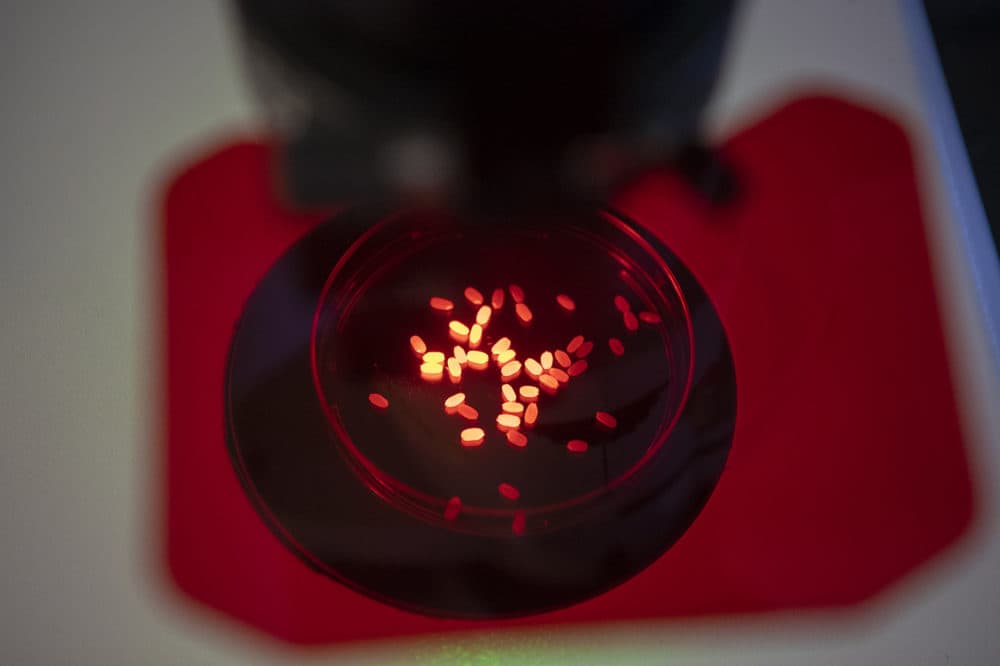

All are familiar sights to some gardeners. But no amateur gardener has ever done what research associate Kieran Ryan is doing in this lab: He's shining ultraviolet light on a Petri dish scattered with grains of rice, to see under a microscope which ones glow red — as part of the process of editing their genes.

"You can see how some of these seeds glow and some of them don't," he says. "There's one in the middle there that doesn't glow."

Ryan and his boss, Olly Peoples, are seeking grains that don't glow, a visual signal that the process using CRISPR — the technique that makes it easier than ever before to tweak genes — to edit one rice gene is complete.

"It's an interesting gene," says Peoples, CEO of Yield 10, an AgTech company — that's agricultural high-tech — in Woburn, Mass. "This gene is almost like a master traffic light. So it slows plant growth."

The company's research in particularly fast-growing prairie grass found that this traffic light gene's activity was turned down in the grass. "So what we've done is, we've essentially said OK, if it's turned down in this high-yielding plant, let's use CRISPR to turn it down in rice," he says. "So, more or less, what he's done is essentially turned that gene off."

Yield10 is aiming to make major crops like rice much more productive. It's using data science to pinpoint key genes that affect growth, and then altering them using CRISPR. The company has already reported dramatic initial results from gene-editing to boost yield in camelina, a plant related to flax.

Peoples portrays the company's work as part of a rising wave of gene-editing that could lead to another 'Green Revolution,' like the huge leap in grain production back in the '50s and '60s — one that's needed as the global population grows. But he says gene-editing could affect agriculture across the board, not just yields.

"It's really a spectrum," he says. "It's everything from the high-yield energy crops all the way down to flavor. Appearance. The non-browning apple. The non-browning mushroom. Lettuce that doesn't wilt. We're in the heavy lifting section, we literally are. The good thing is, it's looking like the shovel is pretty good."

"It's everything from the high-yield energy crops all the way down to flavor. Appearance. The non-browning apple. The non-browning mushroom. Lettuce that doesn't wilt."

Olly Peoples, CEO of Yield10

Last week, a Chinese researcher caused an uproar when he revealed that he had used CRISPR on human embryos. Other scientists and ethicists protested that it's unsafe and highly premature to start using CRISPR on babies.

But the picture is different when it comes to using CRISPR to modify foods. Genetic modifications have been common on American farms for decades, and now, a whole new generation of gene-edited foods — CRISPRed foods, if you will — is on its way, from low-gluten wheat to white button mushrooms that resist browning and heart-healthier soybean oil.

From Picking The Best Seeds To GMOs

For millennia, plant breeding just meant selection: farmers would choose the better plants and sow those seeds. The 20th century saw the advent of a new method called mutation breeding, says professor Tim Griffin, division chair of agriculture, food and environment at the Friedman School at Tufts University.

That means, for example, "Let's take this rice and irradiate it to cause mutations, and see if that gets us something," he says. "That's been done since the '40s."

It has been used mainly in big crops like wheat, corn, rice and soy. Then, in the 1990s, came the first generation of GMO — genetically modified — crops.

Griffin offers one classic example: "They took a gene from bacteria that lives in the soil. They got it into corn and then that corn was resistant to glyphosate, which is a weed killer. And that exchange of the gene is not something that you would just expect to happen in nature, because on one hand, it's a corn plant and on the other, it's a soil microbe."

Opposition to GMOs has focused largely on the increased herbicide use they enable. Nevertheless, in the U.S., corn, soy beans, cotton and sugar beets are now overwhelmingly GMO.

The biggest difference between GMO crops and the new gene-edited foods is that CRISPR is generally used like a molecular scissors, snipping out genes rather than inserting new ones from other organisms.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture announced this spring that it doesn't plan to regulate most CRISPRed crops. The thinking is that they could have been produced with conventional breeding.

"There should be an orderly transparent process for what goes into our food supply. And for a long time, this has not been the case."

Steve Gilman, of the Northeast Organic Farming Association

But exactly how gene-edited crops — and animals, for that matter — should be regulated remains very much in play.

"The problem is that they are GMOs, and it's also a very new and unproven technology that needs a lot more work before it's turned loose" into the marketplace, says Steve Gilman, policy coordinator for the Northeast Organic Farming Association.

He's among those who challenge the notion that CRISPRed crops should be regulated less because they pose fewer risks.

"There should be an orderly transparent process for what goes into our food supply," he says. "And for a long time, this has not been the case. It's been ruled by Big Food, and this is just another case of the technology surging forward in the search of profits."

"No. No more tech," says Julie Rawson, executive director of the association's Massachusetts chapter. "Let's just get back to doing what nature has taught us to do for thousands of millions of years, to raise food in conjunction with nature, and in harmony and in appreciation of nature, instead of dominating it and killing everything in sight."

But at a Boston conference on CRISPR this summer, a prominent organic farmer, Klaas Martens, made headlines when he expressed (very qualified) support for gene editing: "I think there are some uses of CRISPR that would be fully compatible, in my opinion, with the goals of organic agriculture. There are some others that would not be compatible, and I would hope that as an industry, we could go forward and discuss the different uses."

At the nonprofit Center for Science in the Public Interest, biotech project director Gregory Jaffe calls similarly for an examination of whether gene-editing involves inherent risks and how to manage them on a case-by-case basis.

"I'm not pre-supposing that everything needs to be regulated or that nothing needs to be regulated," he says. "I think probably the devil's in the details — some of both," and what's needed is "not just applying old laws into a new technology, like fitting a square peg into a round hole. We should actually look at this in a science, evidence-based manner and move forward after that."

Jaffe is a member of a new national Coalition for Responsible Gene Editing in Agriculture. With industry support, the coalition is trying to work out guiding principles for developers of gene-edited crops and animals.

So Would You Buy CRISPRed Food?

In the coming years, you'll likely start seeing CRISPRed foods on the shelves. But you may not always know you're seeing them. Jaffe believes a pending federal law about disclosing or labeling what's called "bio-engineered food" probably will not include gene-edited foods.

But some CRISPRed foods may actively advertise their gene-edited benefits. Jaffe says that a Minnesota company called Calyxt is expected to start selling "heart-healthier" soybean oil next year.

"If you were a consumer, you'd have to look hard to find this oil," he says, "but the point being there are products that are moving to the farm — and to the food supply."

Some non-browning apples have been reported to have reached store shelves in the Midwest, but for now — at least in the coming months -- it's highly unlikely that you'll encounter CRISPRed food in the supermarket. Most of those novel edited foods — the non-browning mushrooms and tastier tomatoes -- are still only at the proof-of-concept stage.

Until now, consumers had little reason to like GMO foods: the modifications mainly made food easier to grow for farmers, not more appealing to shoppers. A new poll from the Pew Research Center finds consumers pretty evenly split on whether they think GMO food is better for your health, or worse. But Tim Griffin from Tufts says that could shift.

"I think the nutrition and health side of it is probably the game-changer," he says. "And it'll be interesting to see what happens to broader opinions about this if a consumer could look at it and say, 'Oh, that actually might be better for me.' "

So it's not too early to ask yourself: If a label promises you better nutrition through CRISPR, how will you feel about that?

"From the science side, it's really quite a remarkable time," says Griffin. "But a lot of uncertainty — and uncertainty scares some people, some consumers. Others, not so much."

This segment aired on December 3, 2018.