Advertisement

Providers Train To Include Abortion Pills In Routine Primary Care

Resume

Dr. Honor MacNaughton is training a room full of about 40 primary care providers on the basics of abortions using pills, from counseling patients to follow-up.

"Just like anything else we do in primary care, I'm starting it with open-ended questions," she tells the group. "'I understand you had a positive pregnancy test. How can I best help you today?' "

Nearly one-third of abortions nationwide use pills; here in Massachusetts, that rate is even higher: about 40% are medication abortions.

Primary care doctors prescribe plenty of other types of pills for patients. Lately, it seems more doctors are learning how to provide abortion pills as well.

"Medication abortion is super safe," MacNaughton tells the trainees, "and there are actually very few medical contraindications to using the pills — and they're all listed here," she adds, pointing to an information packet.

The class learns that medication abortions are approved for up to 10 weeks into a pregnancy and that the patients take two different types of pills. The pills can also be used to treat early miscarriages.

They also learn how to troubleshoot patients' concerns. For example, MacNaughton explains that the pills bring on cramping and heavy bleeding that tend to last for several hours.

"Then it lightens up, and it's more like a period, or a light period, for nine to 14 days," she explains. "So not like five to seven [in a] normal period — nine to 14 days on average. And that's normal, that's what we expect."

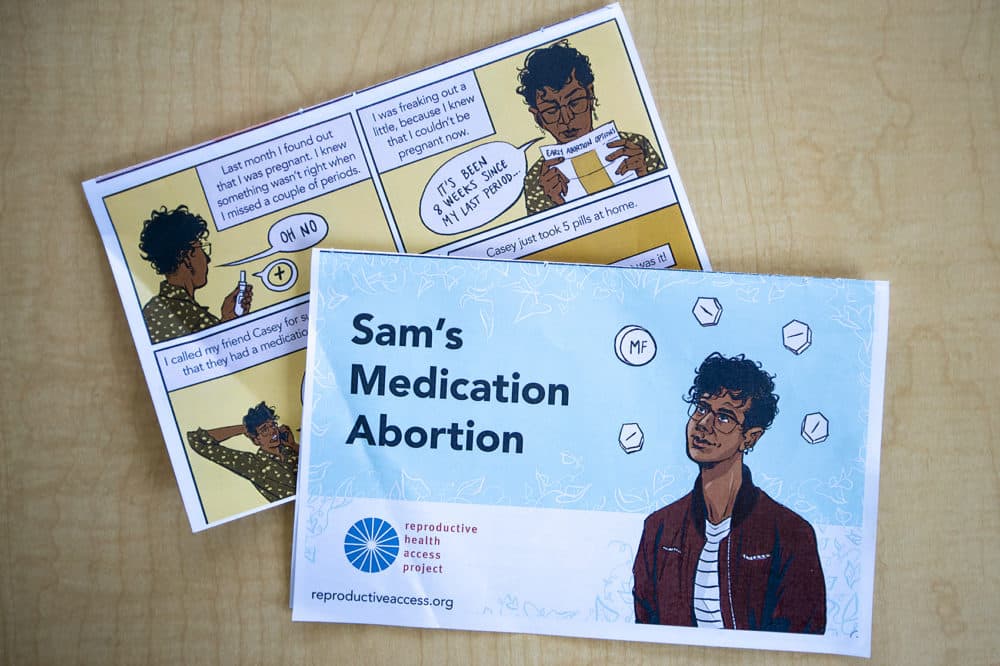

She has been doing these trainings for primary care providers in the Boston area for about a decade, as part of a national nonprofit called the Reproductive Health Access Project.

But against the backdrop of new restrictions on abortions in some states and at the federal level, this month's training was the biggest by far, she says. MacNaughton sees two reasons it was double the usual size.

"One, reaction to what's happening nationally. But also, as there are more and more folks who are trained in Massachusetts, people tell their friends, and so we're seeing some of our community just growing," she says.

That momentum can be seen nationally as well. Last month, an article in the New England Journal of Medicine argued that recent state and federal restrictions on abortion make it imperative for more primary care providers to offer medication abortions.

"As a primary care doctor myself, this ever-changing landscape really highlights the importance of integrating abortion care into routine primary care," says co-author Dr. Jessica Beaman from the University of California at San Francisco. "Especially in order to fill a gap in services, and at a time when abortion care becomes threatened in specific areas of the country."

Of course, those "specific areas of the country" that are restricting abortions are not likely to foster them in primary care either.

But more primary care providers could help even if they practice on the other side of a state border, says Lisa Maldonado, executive director of the Reproductive Health Access Project.

"In a place like Massachusetts, we can possibly integrate into primary care," she says. "And maybe people will be coming to Massachusetts from other states where [abortion] is not going to be available, and to be able to have more access in Massachusetts or in states like it is important."

The nonprofit has built up a network of 3,000 primary care providers interested in medication abortions. It's drawing on a huge primary care pool of more than 200,000 doctors and their support staffs.

Practical Barriers

In Massachusetts, some of the biggest barriers for primary care abortions tend to be practical — for example, one of the abortion pills, mifepristone, has to be stocked in-house; it can't just be dispensed with a prescription.

Dr. Aaron Hoffman recalls that it took about two years to bring medication abortions to Massachusetts General Hospital, where he's a primary care physician.

"It wasn't because of any kind of ideological resistance. It was just because it hadn't been previously done," he says. "So it was really just purely a logistical matter."

But there is also ideological resistance, as MacNaughton acknowledges to the class.

"The harder piece is getting the rest of the folks in your clinic on board to do it. And it can take a long time," she says.

And some staffers may never be on board with it. Dr. Kerry Pound, a Salem pediatrician on the board of Massachusetts Citizens for Life, says medication abortions may appeal to some doctors because they take effect in the privacy of a patient's home.

"But I do think, at the end of the day, most physicians are a little uncomfortable with abortion," she says, "because we go into medicine to really support life and patient health, and at the end of the day, there is a life that's being ended."

And for some, she says, it could be hard even to work in a practice where medication abortions are offered.

"I think I, myself, as a pro-life physician, that would be very difficult for me," she says. "To think that my patients may go over to another doctor in order to obtain an abortion would probably be a deal-breaker for me to work in that practice, to be honest."

On the other end of the spectrum are trainees like Zoe Gordon, a medical resident who plans to become a primary care physician and offer abortions to her patients.

"I feel really strongly that people who don't know that much about biology and health are making decisions about women's reproductive rights," says Gordon, who is from Ohio, one of the states that have recently passed abortion restrictions.

"Part of my drive to get this not only knowledge but also practical information is to be able to provide it to people who don't have to drive across the state to get this very simple and really relatively safe therapeutic treatment," she says.

Primary Care Setting

Currently, it's estimated that only 1% of abortions are done in primary care settings. But MacNaughton says it's hard to know what's happening under the radar. And abortions in primary care offices can be lower profile than dedicated clinics.

"Part of the beauty of being able to offer this care in primary care," she says, "is that when a patient walks in the waiting room, they're there just like everybody else, with a 2-year-old getting his well child check or somebody there for their diabetes follow-up. Nobody knows why that woman is there."

And, as far as she knows, there has never been an anti-abortion protest outside a primary care clinic.

This segment aired on May 24, 2019.