Advertisement

Visionaries

Harvard Professor Still 'Playing Science' And Winning Federal Grants At Almost 94

Resume

Harvard biochemistry professor Jack Strominger has published over 1,000 scientific papers.

He discovered how penicillin kills bacteria. He helped solve the riddle of how our immune system can tell friend from foe.

He's such a star that when his son, the renowned physicist Andrew Strominger, won Silicon Valley's big-money "Breakthrough Prize," the limelight inexorably shifted his way.

"I took my dad out there," Andrew Strominger recalls, laughing, "and people would come up to me and say, 'Here, can you hold my camera and take a picture of me with Jack?' "

In December, in his Harvard office, Strominger shared some good news: "I just got a grant — at age 93."

"Some people play bingo. Others watch TV. Some people play chess. I play science."

Jack Strominger

It was a fairly small grant — $300,000 for two years — but it raised a question: Was Strominger the oldest researcher in the country to win an NIH grant?

"I wonder," he mused.

It took a Freedom of Information Act request to the NIH to find out, but it yielded an answer. No, 93 is not the oldest age of a grant recipient.

The NIH would not say who the record-holder is. But it did say that it is supporting just 13 active researchers over age 90. That's out of about 300,000 funded researchers.

So Jack Strominger is a member of a very elite club. What's his secret?

"Well, I think my secret is, when you reach 93, you have some choices," he says. "Some people play bingo. Others watch TV. Some people play chess. I play science."

Strominger's son, Andrew, puts it differently: "It's doing something that you love. And he just loves it. And it is a wonderful occupation. We live in an incredible universe, and it's just a great thrill to discover it."

Scientific Thrills

Jack Strominger admits he's a scientific thrill-seeker, and always has been, ever since a quirk of fate landed him — an MD, not a PhD — in his own fully funded NIH lab at the crazy-young age of 26.

Strominger set out to figure out how penicillin worked — and he did: it kills bacteria by keeping them from building the walls of their cells. That major advance took about 30 years of work.

"If I realized how complicated the penicillin story was going to become, I might not have ever tackled it," he says. But current efforts to find new antibiotics are still building on that long-ago work.

In the late 60s, inspired by the first human heart transplant, Strominger jumped to working on the immune system, hoping to understand why the body rejects transplants. And he came to Harvard, with his late wife, Anne, and their four children.

Fast-forward 25 years. Strominger and colleagues, primarily the late crystallographer Don Wiley, made a huge discovery: the molecular structure that lets the immune system decide if a cell is infected and should be killed.

"It's comparable to the level of the leap forward we got from something like the structure of DNA," says Daniel Davis, an immunology professor at the University of Manchester and author of "The Compatibility Gene" and "The Beautiful Cure."

Just like the double-helix structure of DNA, Davis says, this structure — of what's called the major histocompatibility complex — illuminated the biology at work. He compares it to a cup or a clenched hand on the cell surface that holds out bits of what's inside, so it can signal the presence of an infection.

"So by seeing the shape of that protein molecule, and then understanding it's presenting samples of what's being made inside cells, that was a huge boost forward in our understanding of how the immune system really works," he says.

Pregnancy Paradox

These days, Jack Strominger is tantalized by a mystery known as "the pregnancy paradox." A fetus is a foreign entity inside a pregnant woman. So why does her immune system tolerate it?

"We live in an incredible universe, and it's just a great thrill to discover it."

Physicist Andrew Strominger

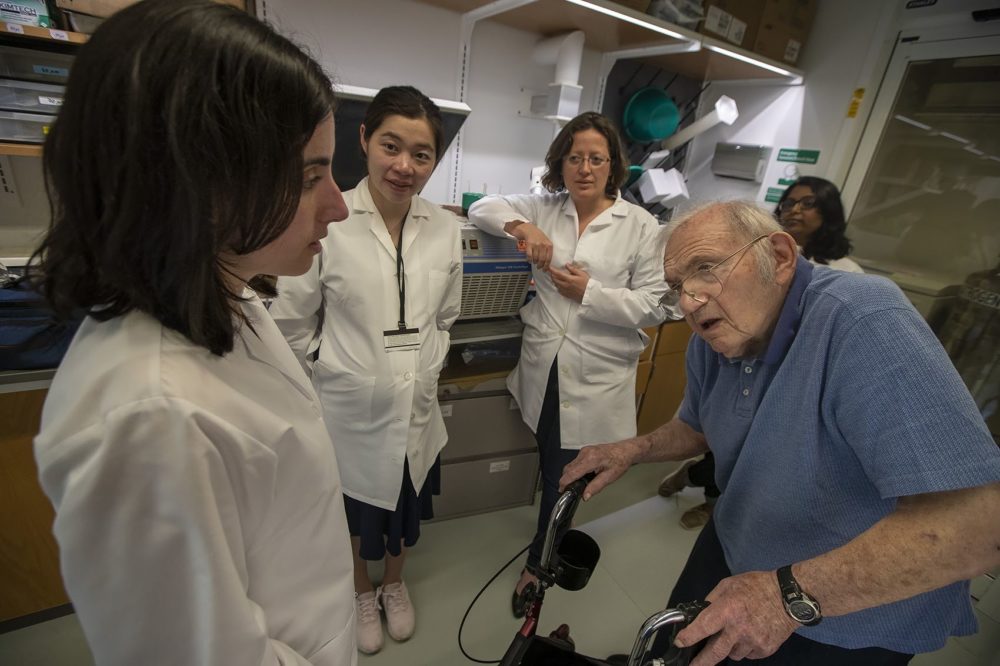

In Strominger's Harvard lab, researcher Tamara Tilburgs removes a fresh human placenta from its plastic container. The baby it used to nourish has been born, and the placenta has been donated to science.

"If you've never seen one before, it's quite big and bloody," she warns.

So it is. It's a very impressive organ, resembling a big purple hamburger patty encased in white membranes, with a foot or two of white umbilical cord snaking out of it. And it's all the more impressive when you consider that it grows nearly as big as a frisbee in a matter of months. But still, at first acquaintance, surely a bit stomach-turning to some.

Tilburgs responds to the suggestion with a good-humored protest: "I think they're actually beautiful!"

She and her colleagues will harvest a dozen different types of cells from the placenta to analyze.

"What we want to do is understand how, during pregnancy, the maternal immune system forms a tolerance to the baby," she says.

Strominger has been wrestling with this question for more than ten years now: What ratchets down the mother's immune defenses so her body tolerates the fetus? What ratchets it back up to fight infections?

It's basic science, but it has high medical stakes: More than ten percent of babies are born prematurely, and one factor could be molecules that trigger the mother's immune system to reject the fetus.

"If you could figure out a way to down-regulate it or to mask it," Strominger says, "you might be able to treat incipient pre-term birth."

"He's successful at getting grants because he's a great scientist. Because he's curious. Because he asks the right questions."

Dr. Judy Lieberman, Harvard Medical School

Strominger focuses particularly on a group of special immune molecules in the placenta. "One of the molecules, HLA-C, has a dual role both in tolerance and in infection, and I'm really curious how it's regulated," he says.

So curious that his mind is working on the problem, night and day.

"I was going to sleep, and I had a great idea that all these four molecules are regulated together by a common enhancer," he recalls of one recent bedtime.

More Good News

In June, Strominger got some more good news: another grant, a big one this time — $4 million over five years, he says — in a major collaboration with Harvard Medical School's Dr. Judy Lieberman.

She says the research will explore much more about how the immune system works during pregnancy. For example, to fight infection in the fetus, immune cells called Natural Killer cells use tiny "nanotubes" to inject a toxin that kills microbes but not fetal cells.

"It's really incredible," Lieberman says. "As far as I know it's the first time anyone has described that killer cells could kill microbes inside the target cell without harming the target cell."

She credits Strominger with central insights into how the mother's body puts the "brakes" on the immune system to protect the fetus.

"He's successful at getting grants because he's a great scientist. Because he's curious," she says. "Because he asks the right questions."

And one added advantage of age: "You become wiser," she says. "The same themes keep coming back, and you develop a kind of wisdom — it's an instinct for what's important."

There's some controversy in science around grants going to older researchers, because it can be so hard for younger scientists to get their careers off the ground. Lieberman calls it a dilemma.

"It's incredibly hard for young scientists to get jobs if, like in my program, a lot of the investigators are getting close to 70," she says.

"On the other hand," says Dr. Isaac Chiu, "the U.S. is a meritocracy, right?" And Strominger "is doing great work."

Chiu started working in Strominger's lab when he was still in high school. Now he's an assistant professor of immunology at Harvard — and still inspired by him.

"When I go and speak to him about science, he still says, ''What I'm doing right now, Isaac, I think is one of the most exciting things I'm doing scientifically in my whole career,'" Chiu says. "So even today, as a 93-year-old, you can see he wants to make the big discoveries."

And they could in fact be big, he says, with implications ranging from auto-immune diseases to cancer.

How Much Time Left?

With his lab funded to keep going, now Strominger just needs his body to keep cooperating.

"I think I've been very lucky that although I've had arthritis problems, my head's remained clear — very clear," he says. "I think maybe one reason it's remained clear is because I use it all the time."

He uses a walker to get around, and hearing aids, but says he's in basically good shape aside from typical age-related health problems. And the age-related looming of mortality.

"I do sometimes say, 'Well, 94, I'm almost 94, how much more do I have?'" he says. "I'd like another five years."

He hopes to write a big paper called "Tolerance and Immunity" that lays out important mechanisms at work. He wants to keep solving immune-system mysteries. And to keep mentoring younger scientists.

"I think my greatest contribution to science has been my students," he says. "I'm very proud of many of them who have contributed enormously."

Making a contribution to science brings a special gratification, says Strominger's son, Andrew: "It's there forever, you know? And your name may or may not be attached to it, but you have this kind of peaceful feeling that you contributed to the world in a way that can't be erased."

At almost 94, Jack Strominger has more of those contributions to make.

This segment aired on July 12, 2019.