Advertisement

'We're Racing Time': Biotech Companies Rush To Complete Coronavirus Vaccine

Resume

As deaths and new infections from the novel coronavirus rise, mainly in China, scientists are working as fast as they can to develop a vaccine that might stem the epidemic.

Time is not on their side.

If scientists are unable to create a vaccine before the virus spreads further and begins mutating, their efforts won’t be as effective in preventing a global pandemic.

“We’re racing time — the virus itself,” says Dan Manichella, the CEO of CureVac, a German biotech company with offices in Cambridge, and one of several companies developing a vaccine. “People are working a lot of long hours.”

Last month, Chinese researchers published the full genome of the new coronavirus and companies both large and small have jumped into the effort. The genetic code is the key to creating a vaccine.

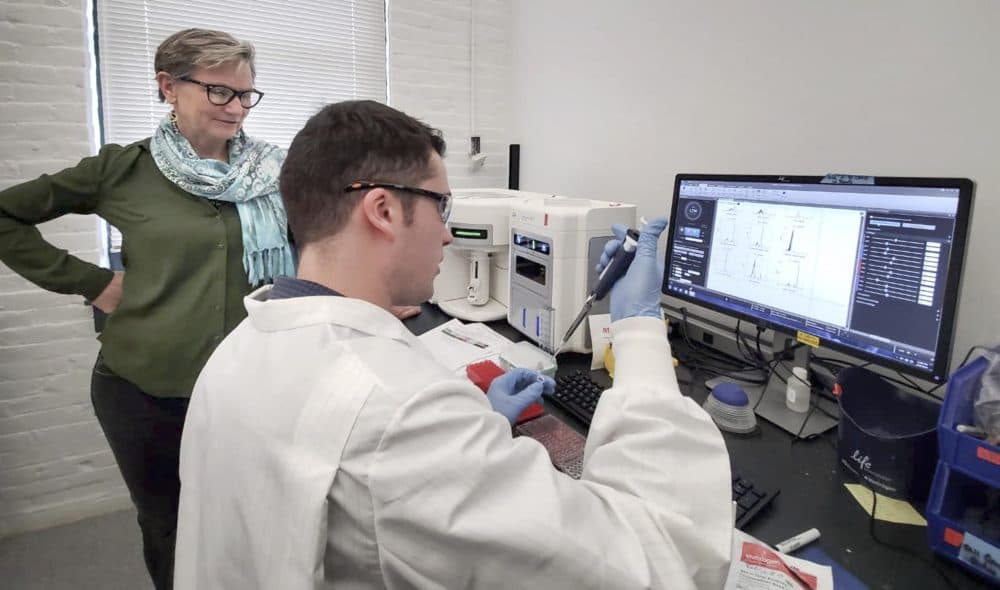

“As soon as the sequence was published, I said, ‘could we please analyze this sequence for potential vaccine design?’” says Annie De Groot, an immunologist and co-founder of Rhode Island-based EpiVax. “Three hours later, we had the essential elements for designing a vaccine.”

De Groot, like other biotech researchers, has been watching the progression of the new coronavirus as it grew into an epidemic.

“I even have a little Excel spreadsheet that I keep on my computer to see what’s going on [in terms of infections] versus what was predicted,” she says. “You very quickly had a sense that there was going to be an urgent need for a vaccine – an urgent need for something that EpiVax could do to help contain this outbreak.”

There are several strategies that researchers and biotech companies are pursuing to build this vaccine, De Groot says. In the sunny halls of a refurbished wool mill, EpiVax employees are designing a peptide-based vaccine. The approach uses peptides, which are fragments of protein, that look like a part of the virus. When injected in a vaccine, the body's immune cells learn to recognize those peptides and destroy anything carrying them — in this case, the coronavirus.

The advantage to peptide-based vaccines is that they can be pushed through development very quickly, while other kinds of vaccines often take months — or even years — to complete.

“You could get into a phase one safety trial within weeks,” De Groot says. “Four weeks at the shortest,” from start to finish.

The disadvantage, De Groot says, is peptide vaccine cannot be easily mass-produced, and they don’t protect against infection.

“It fortifies your immune system so that you don’t get as sick when you’re infected,” she says. “I think it would buy us time.”

Time for other scientists to develop and produce vaccines that can be distributed more widely. Until then, De Groot says, a peptide vaccine could be used to protect health care workers or others at high risk, and it could help slow the spread of the virus.

Boston-based biotech Moderna and CureVac are working on RNA-based vaccines for the new coronavirus. That may take longer to complete.

“We need several months to get the vaccine into phase one clinical trials,” Manichella says. And then, he says, it may take a few more months of testing to get the vaccine into the clinic.

RNA-based vaccines are a new technology that haven't been approved by the Food and Drug Administration yet – but they may present one of the best shots at stopping the coronavirus, says Dr. Michael Mina, an immunologist and epidemiologist at Harvard University.

RNA carries genetic instructions for the body to make proteins. In a vaccine, the RNA supplies codes for a piece of the virus. When injected, human cells begin manufacturing that piece of the virus, which spurs the immune system to create defense compounds to neutralize it. These compounds, called antibodies, can clear viruses from the body before they have a chance to cause illness.

“It’s an ingenious design,” Mina says. “This is very different from other vaccines, where you have to grow the virus, kill it and make sure they are super safe to give to somebody."

With the right RNA code in the vaccine, the body should be able to create defense molecules that will take out the virus. The difficulty is choosing the right bit of code to use in the vaccine, Mina says.

“But if I were putting my money on a company that could pull it off in a short amount of time, I would probably bet on Moderna. Do I think it’s a more than a 50% chance? Maybe not," he says.

Moderna declined to be interviewed for this story. In an emailed statement, a representative said, “We are focused on meeting the [National Institutes of Health’s] timeline for delivery of the vaccine for use in the phase 1 human clinical trials.”

The NIH has partnered with Moderna and expects to have the vaccine ready for the first clinical trials within three months, says NIAID Director Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Whether the vaccine makes a difference in the epidemic depends on how quickly an effective vaccine can be completed, Mina says.

“If it’s in the next month or so – then yeah, it will really make a difference. A year or six months from now – in terms of keeping the epidemic at bay – then that will be too long,” he says.

At that point, the virus may have already spread too far or mutated too much for a vaccine to stem a wider pandemic. That countdown isn’t lost on the researchers at CureVac and EpiVax.

“It’s ‘Honey, I’m not coming home today; I’m designing a coronavirus vaccine,’” De Groot says. “Yeah. It’s been stressful, but you’re trying to address a public health emergency.”

This segment aired on February 21, 2020.