Advertisement

With Old Buildings And Conflicting Needs, Boston Public Schools Face Hard Choices

In May, a month before graduation, parents and teachers at the McKinley South End Academy were surprised by a letter from Carleton Jones, executive director of capital and facilities management at Boston Public Schools.

Jones informed them that the city had received approval to move forward on its plan to build a new school for the Josiah Quincy Upper School — at 90 Warren Ave., South End Academy’s current home.

“The proposal,” Jones wrote, “calls for the Warren Avenue building to be demolished, beginning the summer of 2017.”

“It was a shock, to see it fleshed out on paper: that we were going to be sent to who knows where, retrofitted, to make way for a whole new school with a new group of kids,” said David Russell, who has taught middle-school students in that Warren Avenue building for the past 29 years.

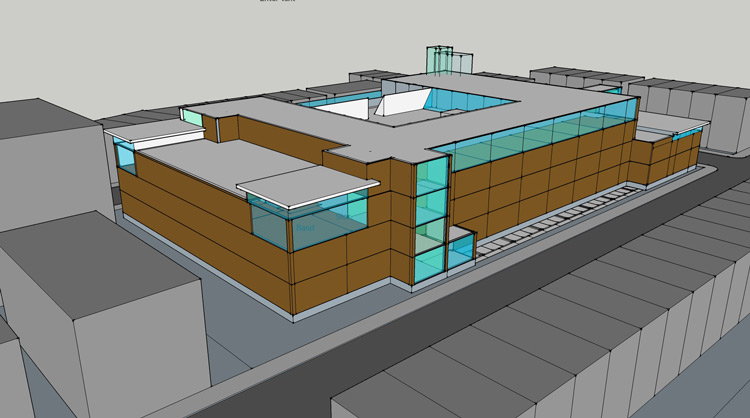

The letter said the Massachusetts School Building Association, a statewide organization that invests in new school buildings, had agreed that the city could go forward with its plan to build a new, $83 million school on the site. Later that week, a schematic drawing of the proposed building surfaced online.

Leaders of the Josiah Quincy Upper School, one of the city’s highest-performing and most challenging high schools, have sought a new building since at least 2010. Their campus is currently spread across three buildings — one built in 1911 and another a 90-year-old converted office building.

Their situation isn’t unusual in Boston. Two-thirds of the city’s 132 school buildings were constructed before World War II, and 60 percent of participants in a recent city survey rated their facilities as “fair” or “poor.”

“We know our building stock is old, and that we need to think about new buildings,” said Ross Wilson, deputy superintendent for administration and innovation. “The No. 1 step is to stop pitting these schools against one another.”

But conflicts do come up — and facilities decisions made at the top tend to speak volumes to teachers and students down below. As city officials embark on BuildBPS, an ambitious 10-year master plan bent on remaking Boston’s facilities for the 21st century, the conflicting claims on the Warren Avenue lot could be seen as a sign of trouble, or a helpful lesson.

The McKinley program — really four schools spread across three campuses, including the one on Warren — play a special role inside Boston Public Schools, as the educators of last resort for almost 400 students with emotional and behavioral problems and very little history of succeeding in school.

That includes students suffering from ADHD and suicidal depression. Some arrive every morning from group homes; others have to transfer in at midyear. The school also suffers more than the usual brushes with violence: Jonathan Dos Santos, who was killed at 16 last year, was a student at McKinley Preparatory School in the Fenway, and several other students have been killed and injured in the past decade.

It’s a vulnerable population that responds to small class sizes, additional guidance counselors, continual close attention, and more than the usual amount of discipline. (Last year, the four schools had the highest out-of-school suspension rate of any non-charter public school in the city of Boston, at 30.4 percent.)

But these students also carry the burden of anxiety about their status in the school system. When the heating fails, or when their buildings are inadequate, McKinley teachers say they hear a refrain from students: “What do you expect? We’re the bad kids.”

Certainly the schools’ mission doesn’t conform to the achievement-driven, college-first vision of success in education. They send just 32 percent of graduates on to any kind of post-secondary education; another 25 percent go on to work. For the rest — 43 percent of students — post-graduation plans are unknown.

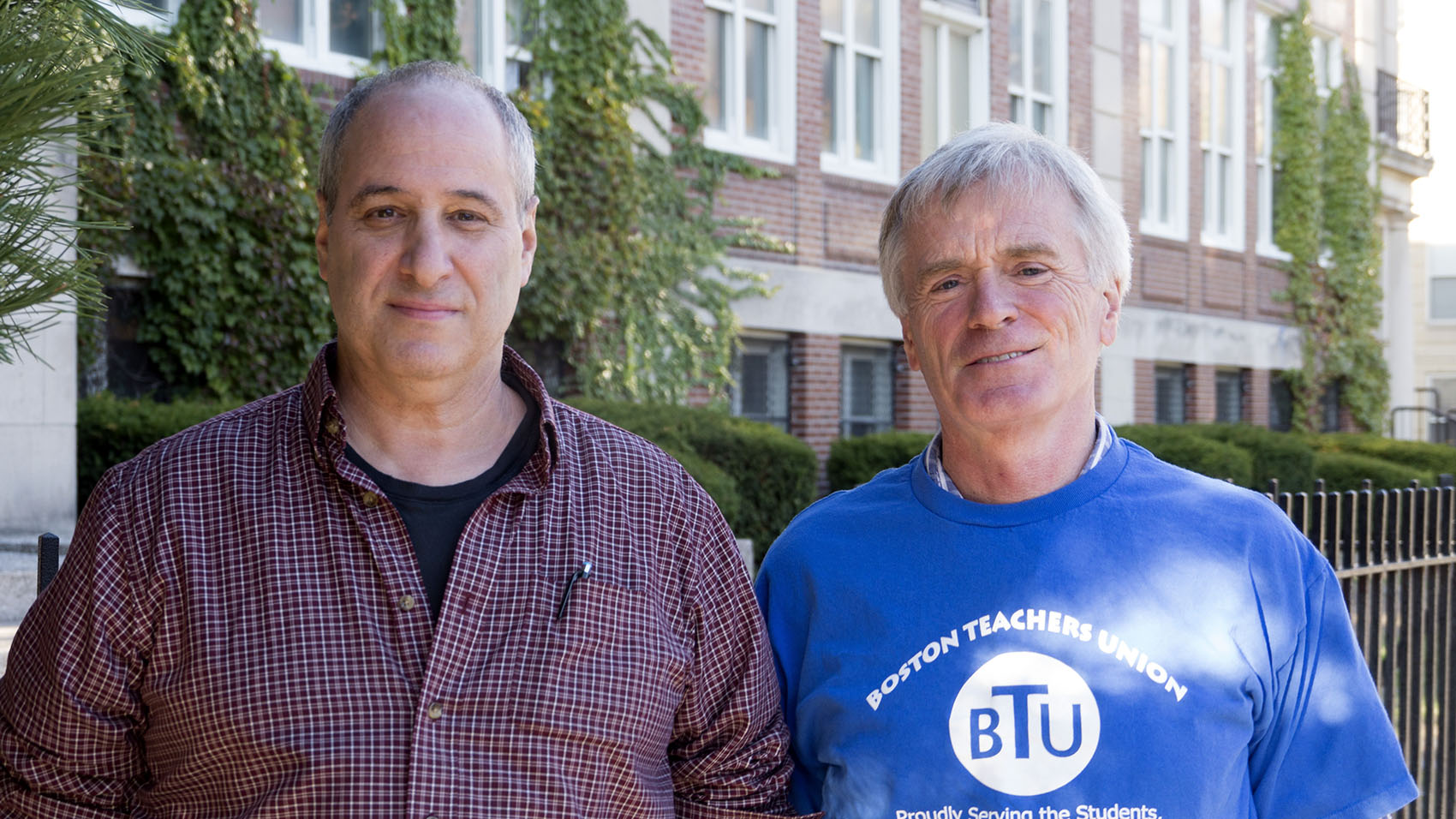

Still, teachers like Warren Pemsler take pride in McKinley’s being a magnet school of a different kind — “the Boston Latin of special education.”

And David Russell keeps an anecdotal measure of how the school is doing: watching children who struggled go on to lead full and happy lives.

“Every year we do have a good number of students who come back to visit,” he said. “They’re 20, 25, 30, they're living on their own, working in such-and-such a place — that is a triumph, against heavy odds.”

“At our school, we’ve created what I call a family,” said Pemsler, who’s taught high school at the South End Academy since 1990. “We try to create an environment where kids feel safe, it’s predictable, and no matter what happens, they understand that we will always continue to be there for them.”

Which is why the demolition plan came as such a shock to people like Juan Lopez of Roxbury. Before his shift at T.J. Maxx, he spoke as a former big man on campus: He graduated top of his class at SEA in June, and was uncommonly popular as a role model and student-athlete.

Lopez’s mother placed him at McKinley in fourth grade after he struggled at both Hamilton Elementary School in Brighton and the Ellison School in Mattapan. Juan Lopez blames lack of chemistry for the two false starts, and spoke of his time at McKinley as a turning point in his life.

“It was so peaceful, so calm,” he said. “It could get hectic sometimes — I mean, it’s high school. But at the end of the day, I could feel comfortable sharing things that normally I don’t share with other people.”

He was upset when he heard about the demolition plan.

“They told me last-minute, in my senior year: ‘Oh, Juan, you’re valedictorian. And the building’s gonna come down.’ What?! That’s not OK,” Lopez said. “That’s home — not just for me but for all the kids that were in there. I feel like that building, where it is now, is perfect for them.”

Pemsler and Russell agree that a better site for their school may not exist. The South End is central, safe, far from the stresses of home and close to vocational and arts opportunities — from Haley House to the Huntington Theatre — that their students would otherwise miss.

The two senior teachers were at the center of a cadre of teachers, parents and neighbors who immediately reacted to what looked like an existential threat against their building. On June 8, they participated in a rally against the demolition plan, carrying signs that read “Put Special Needs First For Once” and chanted, “McKinley, McKinley, we are strong! The South End is where we belong!”

For much of this summer, the campaign to save the McKinley building elicited mixed messages from city administrators.

In response to public outcry, including a petition signed by 1,200 people, both Superintendent Tommy Chang and Mayor Marty Walsh affirmed in June that the building wasn’t going anywhere — at least until, as Chang added, “a new facility is identified that will meet and exceed the educational needs of all McKinley students.”

But later in the summer, Boston facilities staff showed up to assess the site for construction. Neighbors were invited to a “kitchen table talk” about proposed construction on the site “beginning summer 2017.”

David Russell clearly sympathizes with the Quincy Upper School’s predicament, but he added that it felt as if the city forgot there was already a community at 90 Warren Ave.

“One image that came to mind from a colleague was, in a way, it’s kind of like when Columbus discovered America,” Russell said. “‘Ooh, this is a good place. Let’s come here and see what we’re gonna do.’ Oops! There were already people there.”

Wilson of BPS understands the confusion, especially given the due-diligence assessment being done by the city’s facilities staff. But he notes that any definite plan to demolish the McKinley school still would have needed approval from both the MSBA and the Boston School Committee.

Still, the uncertainty persisted until Oct. 4. That afternoon, in a closed meeting, Chang told faculty, staff and neighbors that he had heard their concerns, and that the city would petition the MSBA for another year to come up with a solution.

Outside the meeting, the mood was relieved — but some fears remained.

“I feel a little bit disappointed,” Pemsler said.

Chang had affirmed that the McKinley school wouldn’t be moved without the community’s support. But the prospect of relocation, in 2018 or later, still has not been definitively taken off the table.

“I believe that everything has been done with the best intentions,” Pemsler said, “but I don’t think they understood the true nature of our program, or they never would have even suggested that we move.”

Wilson disagrees categorically that anyone in leadership saw McKinley students as “the bad kids.” But he says that this process has helped the city get to know the school, with its unique needs and contributions, a little better.

The next decade’s building decisions, he said, are bound to be complex, but the city is trying to put its most vulnerable students first.

“There is not an easy answer to go forward here,” Wilson said. “But there was never, ever a time that BPS thought that we would take advantage of any student. And the McKinley students deserve the best. We owe them that.”

This article was originally published on October 17, 2016.