Advertisement

When It Comes To BPS, Walsh Reminds Voters Of His Balancing Act

Resume

This is the second of two articles on the mayoral race and education. The first, about Councilor Tito Jackson's plan for education, was published Thursday.

It’s a cold morning in Boston’s Seaport neighborhood. But for the annual EdVestors "School On The Move" prize breakfast, the Westin Hotel ballroom is full of warmth.

The event is a lovefest, a celebration of excellent Boston principals, teachers and philanthropists, too. Then, there's the guest of honor: Mayor Marty Walsh.

Prize panel chair Jim Stone introduces Walsh by listing the educational accomplishments of his first term: like longer school days at about half of BPS schools, expanded pre-kindergarten classes and a summer learning program.

Most of all, Stone praises the mayor’s consensus-driven approach: “He’s done all this always by building alliances rather than by pitting one side against the other."

As Walsh takes the stage with Election Day on the horizon, he's grateful for the compliment, saying to Stone: “I need to borrow you for the next six days."

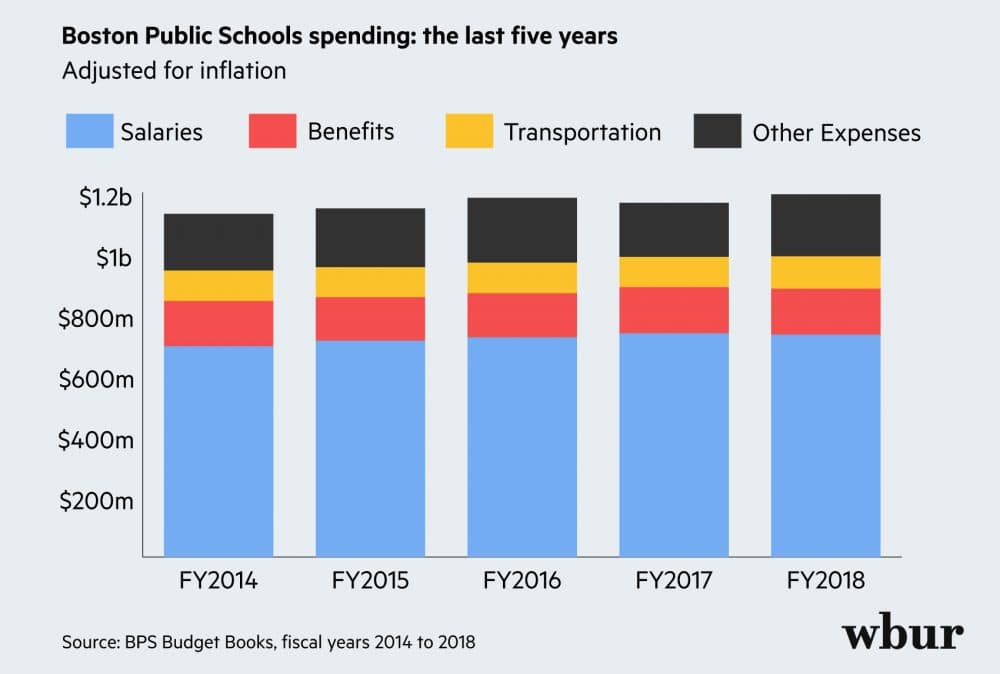

As the incumbent, Walsh is asking voters to judge him on his record with Boston Public Schools. He's increased spending by a little more than 5 percent during his tenure. In a second term, he would embark on a long-awaited $1 billion update to school facilities known as "BuildBPS."

As Boston's warring factions argue about the future of Boston Public Schools, its reputation as a strong urban school system can sometimes be drowned out. (Walsh has occasionally tried to refocus attention on that fact.)

Walsh and others concede that BPS still faces a few big challenges. But there isn't anything like agreement about how to fix them.

Walsh's challenger, Jackson, makes his case for more funding by highlighting the persistence of achievement gaps holding back racial minorities, English-language learners and students with disabilities attending Boston Public Schools.

But so has Paul Grogan, president of the Boston Foundation, a city nonprofit that supports charter schools and education reform.

“Boston is a full participant in one of the great problems facing our nation: failing to unlock the potential of black and brown children," he said.

Grogan believes the BPS budget is bloated by excess staff and capacity, and that the district has to downsize before it can thrive.

But he says he understands why Mayor Walsh has avoided those deep cuts so far.

“Closing schools is — in the political world — a very unattractive thing. Even terrible schools, it turns out, have some defenders," he explains.

Grogan hopes that in a second term, Walsh might take more decisive action against schools seen as failing.

But teachers at one such school couldn't disagree more.

Kristen Leathers and Martha Boisselle are among the few veteran teachers back at Brighton High School this year. They both teach English as a second language.

State data show that in the past five years, Brighton High's enrollment has dropped from around 1,100 students to around 800. Leathers says it's fallen further, to 685. Its test scores have dropped as well, and last year, the state board of education designated the school as under-performing.

Following district policy last year, Brighton High teachers were asked to reapply for their jobs or to leave the school.

Boisselle has taught at the school for 14 years. She says that “fall from grace" does weigh on her.

“It really depends on the day," she says. "Some days you feel hopeful. And some days you feel completely devastated."

During her time there, she says, Brighton's student body has changed dramatically. The immigrant population they serve has grown more diverse.

“Many of them are newcomers, meaning they’ve only been here, some of them, less than a few months," explains Leathers. "They come from all over the world. They speak over 15 different languages.”

State data say 60 percent of students at Brighton High are "economically disadvantaged." A district spokesperson says the school has a larger percentage of homeless students than all but two other Boston schools.

They're wonderful kids, the teachers say, but ones that need more resources to educate — not fewer. They would like to see more counselors to help students deal with traumatizing events. On Halloween night, a Brighton High student was shot and killed in Jamaica Plain.

“We have school psychologists this year, which is really helpful," Leathers says. "We don’t have enough guidance counselors ... social workers. We don’t have enough teachers.”

Boisselle says that, in effect, the state has punished Brighton High for changes out of its control — and that the city hasn't picked up the slack.

Walsh visited Boisselle’s classroom on the first day of school this year. But she didn’t have a chance to make Brighton’s case.

“I would love to sit down and talk to the mayor about this," she says. "It’s been hard to figure out: who do we go to, to advocate for our students?"

Walsh remembers that visit well. Back at the Westin Hotel, he rattles off facts about the population at Brighton High.

"Forty-four percent of the kids in Brighton High are English-language learners," Walsh says. "And if you look at the kids that took the 10th-grade MCAS, many of those were brand new into the country, into the school. And by the time they're 12th graders, they were speaking proficiently in English."

He faults the state for failing to recognize that progress, or to provide the district with sufficient aid. In both respects, help may be on the way. Massachusetts' latest education plan allows state policymakers to reward the kind of student growth Walsh is describing. And on Beacon Hill, Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz has prompted discussions about a big increase in state aid.

Walsh has said he isn't currently planning to close schools like Brighton High, even if students flee for greener pastures. In a second term, he hopes to use special turnaround grants and BuildBPS to bring new life back to those schools. A district website says under new classroom plans in BuildBPS, the system won't have excess capacity in its buildings.

But Walsh isn't letting struggling schools off the hook, either. "You can't continue to fund schools that are losing enrollment at high levels," he says. "Throwing money at a situation and not fixing the problem is not the answer."

It's a middle ground, one that leaves Walsh open to criticism from across the political spectrum. He says again, "Everyone wants more."

That's the challenge facing an incumbent mayor. Everyone does want more for Boston Public Schools: more funding, more accountability, and more progress — and all at the same time.

This article was originally published on November 03, 2017.

This segment aired on November 3, 2017.