Advertisement

What You Need To Know About The Failed Education Funding Bills

As the legislative session drew to a close late Tuesday night, a landmark education-funding bill died — under somewhat mysterious circumstances.

That bill was ambitious: It might have driven hundreds of millions of dollars in state aid to schools — especially in low-income communities — over the course of its implementation. And it has been years in the making, dating back to 2014.

The legislative collapse has left Massachusetts families and educators with a lot of questions. We’ll try to answer a few of those here.

Massachusetts spends more than the national average on education. How much more? It depends on how you count.

If you thought Massachusetts was already a top spender when it comes to public schools, you’re not wrong. But the story's also a bit more complicated than that, and it all comes down to how you count.

According to the latest census data, the Bay State spent about $15,593 per pupil in the 2016 fiscal year. That places it eighth among the states in terms of raw dollars spent.

In the past, this has led some to question whether more a big wave of new spending is necessary — at least in some precincts.

For example, Paul Grogan, director of The Boston Foundation, calls attention to the fact that Boston’s teachers remain in a race with New York City’s to be the best-paid urban teaching corps in the nation.

But of course, raw dollars aren’t the only metric. Everything costs more in Massachusetts. In terms of median rent, for example, Boston is among the most expensive cities in the country.

When you adjust for costs like that, Massachusetts ranks closer to 16th among the states in terms of per-pupil education revenue, at least according to 2013 data compiled by the nonprofit organization EdBuild.

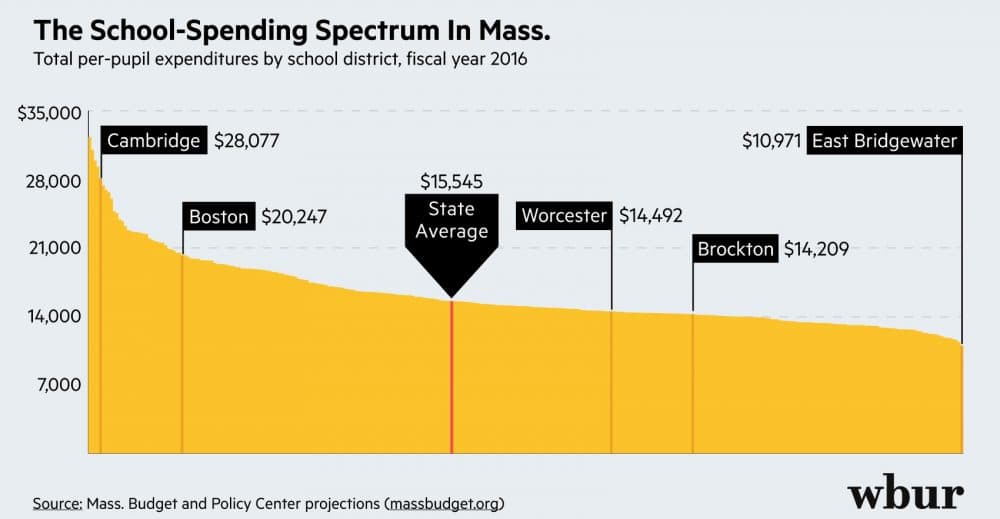

That $15,593 average conceals a wide disparity between what districts spend per student — from under $11,000 in East Bridgewater to over $30,000 in Provincetown.

(What’s more, per-pupil expenditure is itself an imperfect metric, since it masks how spending interacts with different levels of student need. Diverse Brockton, for instance, spends more than $14,000 for each of its students — but it’s still barely meeting the state's funding minimum.)

Massachusetts is more middle-of-the-pack when it comes to public education “effort,” too — meaning the percentage of all tax revenue that is spent on schools. According to the news site Education Week, Massachusetts spent about 3.4 percent of its taxable revenue on education — just 0.1 percentage point above the national average — in 2014.

Nevertheless, school spending is not directly correlated to educational outcomes — and Massachusetts is still regarded as the top public-school system in the country, including by Education Week’s comprehensive annual survey.

In short, it’s a profoundly mixed picture.

“We lead the country in reading by fourth grade — with about half of our kids proficient readers,” said Noah Berger, who helped develop the original funding formula for public schools back in 1993. Berger is now director of the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center, a think tank that has argued for more education funding.

"Now it's great that we lead the country. But if half of our kids are being left behind, that could have significant long-term negative effects," Berger said.

Boston doesn’t stand to get much out of foundation budget reform as it is — but it could have gotten something.

Boston city officials have said this week and for years beforehand that planned changes to the foundation budget wouldn’t provided much, if any, help for schools in the capital city.

Like this from Boston School Committee chairman Michael Loconto:

One independent projection, put together by Noah Berger and Mass Budget, found that the city stood to receive about $30 million under the full implementation of the Senate bill.

But city officials say that by their analysis, neither of this session's final bills would have generated any additional aid for the city.

It's true that Boston is in a class by itself due, in part, to the way the state targets and packages education aid. Because the city's revenue from property taxes is high and growing quickly — note those rising skyscrapers! — the funding formula treats it more like a leafy suburb than an urban district educating 57,000 students from very diverse backgrounds.

Also, every year, thousands of students leave Boston’s district for charter schools, each taking thousands of dollars of city revenue with them.

Under existing law, the state is supposed to reimburse the city for that lost tuition for a period of years. But lawmakers’ failure to fully fund that reimbursement for the past five years has cost Boston alone around $100 million. City officials expect to lose another $25 million during this fiscal year.

If the foundation budget bill had passed, the price of charter tuition would have risen without a commensurate increase in those reimbursements, which would dampen, if not erase, any gains they might have won under the bill.

We could boost education funding without a big new stream of revenue — but it would certainly help.

When Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz of Jamaica Plain prepared to introduce her version of the first funding bill in April, a proposed “millionaire’s tax” earmarked to fund education and transportation was still headed for the ballot.

That tax, Chang-Diaz said, could help her bill's political prospects and its implementation — but she didn’t think a new fiscal windfall was necessary.

Three months later, when the more targeted House version of the bill surfaced, Chang-Diaz’s counterpart in the House, Rep. Alice Peisch of Wellesley, acknowledged that the Supreme Judicial Court’s decision in June to strike that tax off the ballot had “changed the landscape.” But she also denied that the House bill was designed around cost-cutting, pointing to its more ambitious five-year timeline for implementation.

The state is obligated under law to provide for an "adequate education" for all students, and a court could find that it isn't meeting that obligation and compel new spending.

Berger agreed that new funding is almost a prerequisite of a suitably ambitious investment in schools: “I think that to provide high-quality education to all of our schools — to make sure we have adequate funding to do that — probably does require a new state revenue source.”

We have a general idea of how much more it costs to provide low-income students with an excellent education — but we'll never have an exact one.

The conference-committee process under which the final negotiations fell apart is, frankly, opaque. When lawmakers from both houses meet to try to reconcile different pieces of legislation, they do so behind closed doors and with an honored norm of confidentiality.

But we did get a glimpse of the House conferees’ perceptions of what happened in those meetings in a statement released on Wednesday.

Those representatives — Peisch, Claire Cronin of Easton, and Kimberly Ferguson of Holden — wrote: “Negotiations were complicated by new information obtained from the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and the exceptionally complex nature of recalculating various increments to the formula as we traded proposals.”

The idea of uncertainty about the amount of spending required for low-income students dates back to the 2015 blueprint for funding reform, the product of a yearlong commission that Peisch and Chang-Diaz co-chaired.

That blueprint found that low-income students benefited from extended learning time, added social-emotional support, smaller class sizes and high-quality early education. But it acknowledges that different districts would need discretion over how to pursue those programs.

So while the report calculated precise adjustments when it came to employee benefits, special education and English learners, it proposed adding between 50 to 100 percent of funding when it came low-income students. And it left room for “further review of data and debate."

For the purposes of Mass Budget’s projections, a bill that had aimed to increase the “foundation budget” for low-income students by about 70 percent — a middle number — would have added a total in $370 million in state aid to districts by the time the changes were fully implemented.

Three out of five Massachusetts districts — including many wealthy ones — would have received some additional aid under that projection. But more than a third of it would have gone to 45 low-income districts.

Because of the secrecy of the conference committee, we don’t know what new information might have thrown negotiations into confusion.

Students won’t miss out next year because the foundation budget bill didn’t pass — but spending trends won’t turn around, either.

Many state education activists were in high dudgeon after the bill died Tuesday night.

In a mass email, Charlotte Kelly, executive director of the Massachusetts Education Justice Alliance, an activist organization that supported more spending, wrote: “Parents will wake up today and have to tell their kids why they won’t have librarians, or field trips, or new books next year because the State House failed them tonight.”

Tracy Novick, a staffer at the Massachusetts Association of School Committees who also supported the reform, nevertheless pushed back on Kelly’s rhetoric on Twitter:

Indeed, both of the bills under consideration would have ramped up spending over multiple years. Even if the more ambitious bill had passed, districts would not have seen a budgetary bump this year, and no impending cuts will result directly from the legislature’s failure to pass it.

At the same time, the threat of teacher layoffs and other cuts are an annual reality for many districts across Massachusetts.

“I don’t think there’s any low-income city in Massachusetts where people can look at [it] and say that they really have the resources they need to provide high-quality education for all their kids,” Berger said.

For example, Chicopee, Everett, Brockton, Leominster and Southbridge — the last a district currently under state receivership — have all recently warned of or made mass layoffs in response to budget shortfalls.

Under the fully-implemented Senate bill, Mass Budget projected those five districts alone would receive nearly $93 million more per year from the state, which would likely curb future budget squeezes or reverse cuts to services like libraries, counseling or transportation.

Berger added that some less affluent districts are doing better than others, and that state leaders should learn from them even as they find ways to spend more on the whole.

There is still systematic change on the table, and a model to pursue it. But in the meantime, lawmakers may elect to use informal session to spend $72 million of this year's large budget surplus on school safety, as Gov. Charlie Baker has proposed in a supplemental budget. That would include $40 million for social workers, counselors and psychiatrists.

Editor's note: We have updated this post to reflect disputed analyses of what the city of Boston stood to receive from different versions of the "foundation budget" bill.

This article was originally published on August 03, 2018.