Advertisement

Amid Building Woes, Students Ask Boston School Officials Not To 'Wreck The WREC'

Resume

On Wednesday night, the Boston School Committee will vote on the district's recommendation to close two high schools housed in one mammoth building at the city's outer limits.

Together, West Roxbury Academy (WRA) and Urban Science Academy (USA) occupy the West Roxbury Education Complex (WREC). They’re home to almost 700 students, around 80 teachers and a long history of district restructuring and "fresh starts."

If approved, these will be the first school closures to take place as part of BuildBPS, the 10-year reworking of the physical and operational footprint of Boston Public Schools, coming at an initial cost of $1 billion.

With a yes vote, the schools would be set to close in June. Many students are still unsure as to where they might end up next fall, though the district has promised to direct some students to suitable schools next year.

These would also be the first closures to go forward under Laura Perille, the district’s interim superintendent.

Perille acknowledged that the decision to close the WREC is “a very difficult thing,” but says that the “significantly deteriorating” condition of the building has made the closure necessary.

That hasn't convinced everyone in the community.

Some say the schools shouldn’t pay the price for years of official neglect and that if the district wanted, it would repair the WREC while holding students in a "swing space."

That includes some members of the city's school committee, appointed by Mayor Marty Walsh.

Back in October, when the closure was first proposed, Jeri Robinson said, "What if a tornado hit Boston Latin School? We would not be talking about dispersing that community and moving on. We would be figuring out how to keep that community solid no matter where it went."

Robinson added: "Why are we not affording that same kind of respect to all of our schools?”

The State Of 'The WREC'

It was a very different time in Boston when the WREC building opened in 1976. Then, it was West Roxbury High School, opening just after the city's riotous conflict over desegregation busing had reached its peak.

In an article in The Boston Globe from that fall, the school building was described as “something you’d see up the street in Needham or Natick or some other suburban school system.”

The complex cost $21 million to build — $93 million today — and featured then-rare amenities, like air conditioning, elevators and "a 30,000-volume library."

Today, though, district officials say the WREC has become a genuine concern — and they're shouldering some of the blame.

John Hanlon, the district's chief of operations, says the decision was driven by "a facility emergency that, at this point, we have no control over," citing years of deferred maintenance.

In July, district officials told city inspectors “they had real concerns" about the WREC's state of repair. That’s according to William ‘Buddy’ Christopher, head of Boston’s Inspectional Services Department.

Earlier this month in a meeting with parents, Christopher recited some ominous findings: crumbling masonry and “water migration” through the building that could end up damaging other vital systems in the building, including electricity and fire protection.

Christopher told parents he agreed with the district’s proposal to close the school, saying “these aren’t the kind of things you can fix over the summer.”

“The amount of money they would spend, if they chose to fix it, would be Herculean,” he added.

District officials have said they didn't discover the extent of the structural problems until that summer inspection.

But they have also said that this isn't just a facilities issue.

That problem is "coupled," Perille said, "with the long-standing enrollment declines that both of these schools have struggled with."

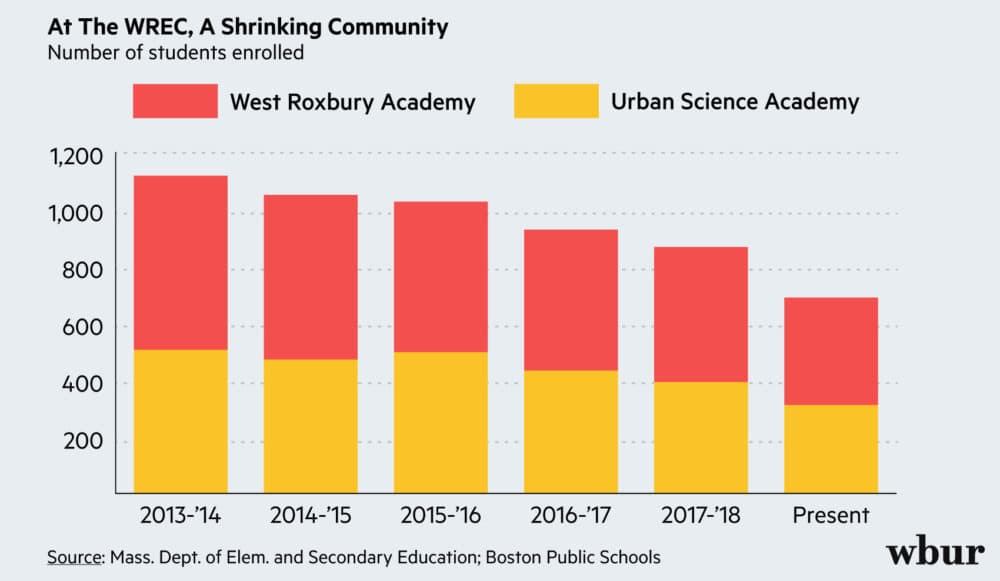

The combined enrollment at the WREC is down by almost 40 percent since 2013.

Perille noted that this is a structural problem the district has to tangle with: At 10 of the district's biggest open-enrollment high schools, enrollment has shrunk by almost 13 percent over the same period.

But the two WREC schools, she said, are also facing particular "academic challenges." The state accountability system judged West Roxbury Academy, in particular, to be in the bottom 4 percent of schools statewide — though community members contest that characterization.

The district's case for closure is based on an education version of triage: A facilities emergency, alongside troubling institutional trends, has forced them to act fast.

At public meetings, many parents were persuaded of the district's goodwill. Like Donna Lashus, whose granddaughter attends the school.

"I appreciate that the superintendent was very transparent with families about the condition of the building," Lashus said. Though, she added, "the timing was late — we should've known ahead of time."

That rhetorical move doesn't satisfy Dr. Miren Uriarte, who stepped down from the Boston School Committee at the Dec. 5 meeting after four years of service.

Uriarte said the district should try to "separate the issues having to do with the building from the issues having to do with the two learning communities."

"So far I haven’t seen a good argument for the destruction of those communities," Uriarte added.

'Trouble Being Motivated'

The news that the school could close came as a shock to juniors and seniors who had begun to think of graduation.

Since October, those students have become mainstays at a series of public meetings on the planned closure, wearing school shirts and stickers that say, "Don't Wreck The WREC!"

Many had arrived at the campus after years of difficulty: One senior student had survived the earthquake in Haiti, while others ping-ponged around public education.

Franco Yee and Joseph Acquah, for instance, were looking forward to dueling to reach the top of the class over the course of the next year.

Yee is 18, and attended charter and virtual schools before coming to campus. Acquah was born in Ghana.

Another newcomer has become a leading spokesman for the schools' cause: Catari Giglio was born in Italy and lived in Chile and Miami.

Earlier this month, Giglio told the Boston School Committee that her globe-trotting youth meant she arrived at WRA this fall with a crippling fear of change.

"The first day of school here," she remembered, "I was crying nonstop, sitting in the library and waiting to get my schedule. I was absolutely terrified, and all I wanted to do was go back home."

But then, Giglio went on, the school became her home: "Thanks to my new friends and teachers, I found a new confidence in myself that I had never seen before. I walk through the halls of this school like I've been here for years."

In those three short months, Giglio's grades improved. She outgrew her shyness and even wound up as "homecoming princess."

When asked why the school worked on her, Giglio said she felt that the teachers and classmates were unusually welcoming.

Rebekah Julmiste, another junior, agreed.

"The first summer I moved to Boston I was a freshman. And I'd walk in the hallways and everybody would say hi, even though they didn't know me," Julmiste said. "It hit my heart, you know?"

The prospect of another home lost — this time to closure — hits especially hard for Giglio and her classmates.

"I've heard a lot of people be like, 'We're having trouble really being motivated,' " Giglio said.

A mounting body of research suggests that students’ academic performance tends to suffer after their school is closed, alongside any emotional trauma the change might inflict.

Then there's the more pedestrian concern: missing out on the glories of senior year.

"It maybe sounds stupid, but you wait to be a senior. You're like the king of the school. You know? I feel like that's basically what a lot of people wanted," Giglio said. "And they're not gonna get it."

The district has said current juniors at the WREC will have the option of moving, together, to the top floor of the Irving Middle School in Roslindale.

But there won't be underclassmen there, or athletic fields. "Probably they're not even gonna want us there," Giglio laughed.

With that plan in such uncertainty, Giglio and several other juniors say they are tentatively planning to transfer to another public high school, despite the district's offer.

Missed Opportunities

Veteran teacher Allison Doherty has been frustrated by the conversation around her school.

She began at what was then West Roxbury High School in 1999, and has held on through a host of proposed and actual changes as BPS has tried to find the ideal form for its high schools.

In 2005, West Roxbury High School was subdivided into four small schools. Then, those merged into two schools: USA and WRA. Those schools were themselves expecting to merge in the year ahead.

"And then come October, they said, 'You're not merging — you're closing,' " Doherty said.

All the while, she added, conditions in the building were worsening, with teachers sending regular complaints to the district.

Nothing the district has proposed so far, Doherty said, has addressed that history of neglect. "Instead of saying, 'We're sorry, we're going to find something to make this right,' it's, 'We're sorry — but suck it up.' "

Doherty founded a program called Symphonize that allows some of the WREC's autistic students to take general-education courses on their way to a diploma. She said she is glad that the district has prepared to send that program, as a cohort, to the Burke High School in Dorchester, which has a good reputation with similar students.

But that alone doesn't offset the lack of trust she's seen grow up in her lifetime inside BPS, both as a student and as a teacher.

"[Officials] will say, 'We've had meetings and we've listened.' But having meetings and listening doesn't mean that you're collaborating," Doherty said.

The BuildBPS plan is broad and further closures or reconfigurations are already on the cards. The McCormack Middle School, on Columbia Point in Dorchester, is set to close in the summer of 2020.

The hope, for many families and educators, is that the feeling of rush and resistance around the WREC plan will encourage the district to reassess their approach going forward.

Uriarte said there's a duty of empathy in cases like this one, "a recognition that this is, for [students], a crisis."

Perille and others say they're determined to help affected students through the transition, with broad plans as to where they hope to send students on specialized education plans.

And Hanlon, the district's chief of operations, said part of the rationale for BuildBPS is preventing things like the WREC "crisis" from happening again.

"I don't want anybody to have to make these decisions," Hanlon said. "And I don't want any of our students to have to live through these decisions. So yes: I am hopeful that BuildBPS will set a standard that we can follow for the next 50 years."

This segment aired on December 19, 2018.