Advertisement

Maine School Districts Under Pressure Amid Spike In Homeless Youth

Resume

Maine is seeing a growing number of young people, from preschool through 12th grade, who are homeless or displaced. They are moving into shelters, couch surfing with other families and, in rare cases, camping or living in cars. According to the National Center for Homeless Education the number of homeless youth increased by 30% in just two years.

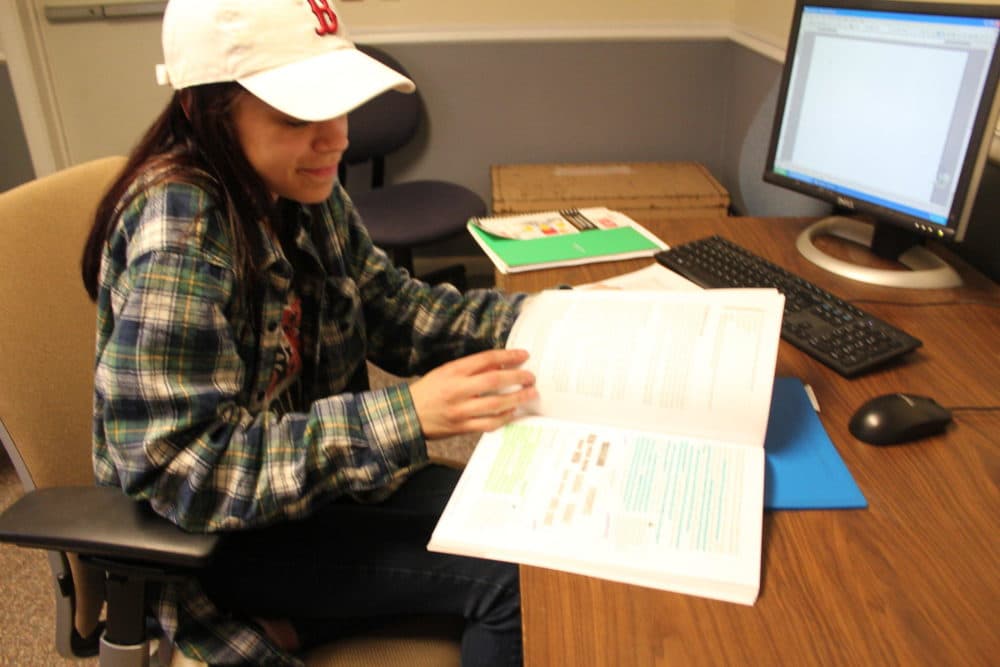

Most afternoons, 18-year-old Mikaylah — she asked that we not use her last name — sits by herself, hunched over a computer or notepad in a back office at New Beginnings, a shelter in Lewiston for youth who are homeless or displaced. Here, she writes stories and letters to help her process what she has experienced over the past few years.

“It gives me more positive memories to all of these traumatic events than what I usually would think about,” she says.

Mikaylah arrived in Maine about three years ago from Connecticut, where she and her sisters had been raised by their single dad. When he passed away, they moved to Biddeford to be with family.

Mikaylah graduated from high school and even enrolled in community college last fall, but she says without an adult to turn to, she did not know how to handle financial aid or pay for books.

“It was hard to think about, who would I even call? Because my family, like, I said, being first-generation, they wouldn't even really know. So it's me asking them questions. 'Who do I call? How do I do this?' ” she says. “So I was literally just kind of living in the dorms, but not going to classes, because I didn't have books, and wasn't doing much of actual school. I was like, I think it's time to just drop out as opposed to paying tuition for nothing.”

She did drop out. But once she left the dorm she had few options of where to go.

Mikaylah says she tried to stay with her grandmother but was asked to leave after repeated family conflicts. She says her boyfriend's sister paid for a hotel for a few nights. But without a permanent place to stay, Mikaylah and her boyfriend passed the time in 24-hour fast food restaurants just to have a roof over their heads.

“Eventually, a couple nights, my friend let me stay in her hallway outside of her actual apartment. We would stay there,” she says. “There were other nights we'd just be sitting outside, trying to figure something else. It was just months of panicking. That's all we could think about.”

Mikaylah is one of a growing number of Maine youth identified as homeless or displaced. According to one measure reported in 2017, more than 2,500 students didn't have safe or permanent housing across the state. That’s a 30% jump from two years prior.

The problem is placing pressure on schools and social service agencies across the state, stretching a system that has already seen cutbacks in recent years.

“We're not alone in that. It's really been a trend across the country,” says Gayle Erdheim of the Maine Department of Education.

Erdheim works with public schools to support students who are homeless or displaced. She says that it is hard to point to any single factor that is causing homelessness to rise. It may partially be the result of better reporting and recently reauthorized policies that require schools to put more effort into identifying displaced students.

“In terms of keying schools in to the value of bending over backward to keep kids stable in the school they've been in, even when they're moving around,” Erdheim says.

But advocates for youth in Maine point to larger, societal problems as part of the explanation that's driving the trend. These include a lack of affordable housing, especially in southern Maine.

The problem is compounded for the many immigrant families and unaccompanied youth who arrive in Portland's shelters, often seeking asylum from violence in their home countries.

“So the folks we see don't have help, don't have caseworkers, don't have jobs, don't have legal standing,” says Susan Wiggin, the transition specialist for Portland Public Schools. “They have the clothes that they're wearing, and that's it. We have to do a lot of shoring up in our schools from elementary school, all the way through.”

In more rural areas, there are other destabilizing factors, like intergenerational poverty, the opioid epidemic and discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation.

Melissa McEntee, the executive director of Rumford Group Homes in Oxford County, says the public may not grasp what is actually happening.

“I think one of the biggest myths we see is people who think it's just runaways who don't want to live under their parents' roofs or their parents' rules,” McEntee says. “That's just clearly not what we saw. It's youth that faced a lot of family conflict, youth that were coming from homes with major substance use, domestic violence, youth that were not able to safely live in their homes.”

The state has a network of connected shelters and support services that help, and school districts are required to identify homeless students and provide education, transportation and support under the federal McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act.

In Biddeford, local officials say the school department has seen its transportation costs rise by 40% in the past five years. At times, the district has relied on taxi services to help get some homeless or displaced students to school.

Superintendent Jeremy Ray says there has been an effort to address trauma and hire more social workers in recent years, but the complicated needs pose a challenge.

“As we look at doing work with students who experience trauma, and all those pieces, where does it all fit in?” Ray asks. “How does that flow out and fit in to the standards that teachers are required to teach? And that we can actually try to do a good job at everything. And I'm not sure, that our setup in seven hours allows us to do that.”

For kids who have aged out of the school system, there is a network of shelters that offer support. For Mikaylah, that support came from the New Beginnings shelter in Lewiston. She says getting counseling and a place to sleep has made a big difference in her life since she arrived about a month ago. She is considering nursing school, and says she hopes to give community college another try this fall.

“So I definitely feel a lot better now that I've had somewhere to be, where I have resources around me, and I've had time not to have chaos and be able to figure everything else out that I need to on my own,” Mikaylah says.

While Mikaylah has found help in a city shelter, homeless young people in rural Maine still face separate, persistent challenges on their own — with no easy solutions in sight.

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative and originally aired on Maine Public. Maine Public reporting on issues affecting teenagers and young adults in Maine is made possible with support from the John T. Gorman Foundation.

This segment aired on May 16, 2019.