Advertisement

Coronavirus Coverage

In Lawrence, Shift To Remote Learning Could Deepen Existing Inequalities

Resume

En español, traducido por El Planeta Media.

Lucero and Jesus miss being at school.

They are 5 and 10 years old. They’re playing while their mom, Margareth Jesus, gets ready for work at a factory in North Andover.

Their father has recently been in the hospital with complications from diabetes.

She tells her friend she might have to send her kids back to the Dominican Republic so their grandmother can take care of them. And she starts crying.

"I've never been separated from my kids", she says, "they are my life.”

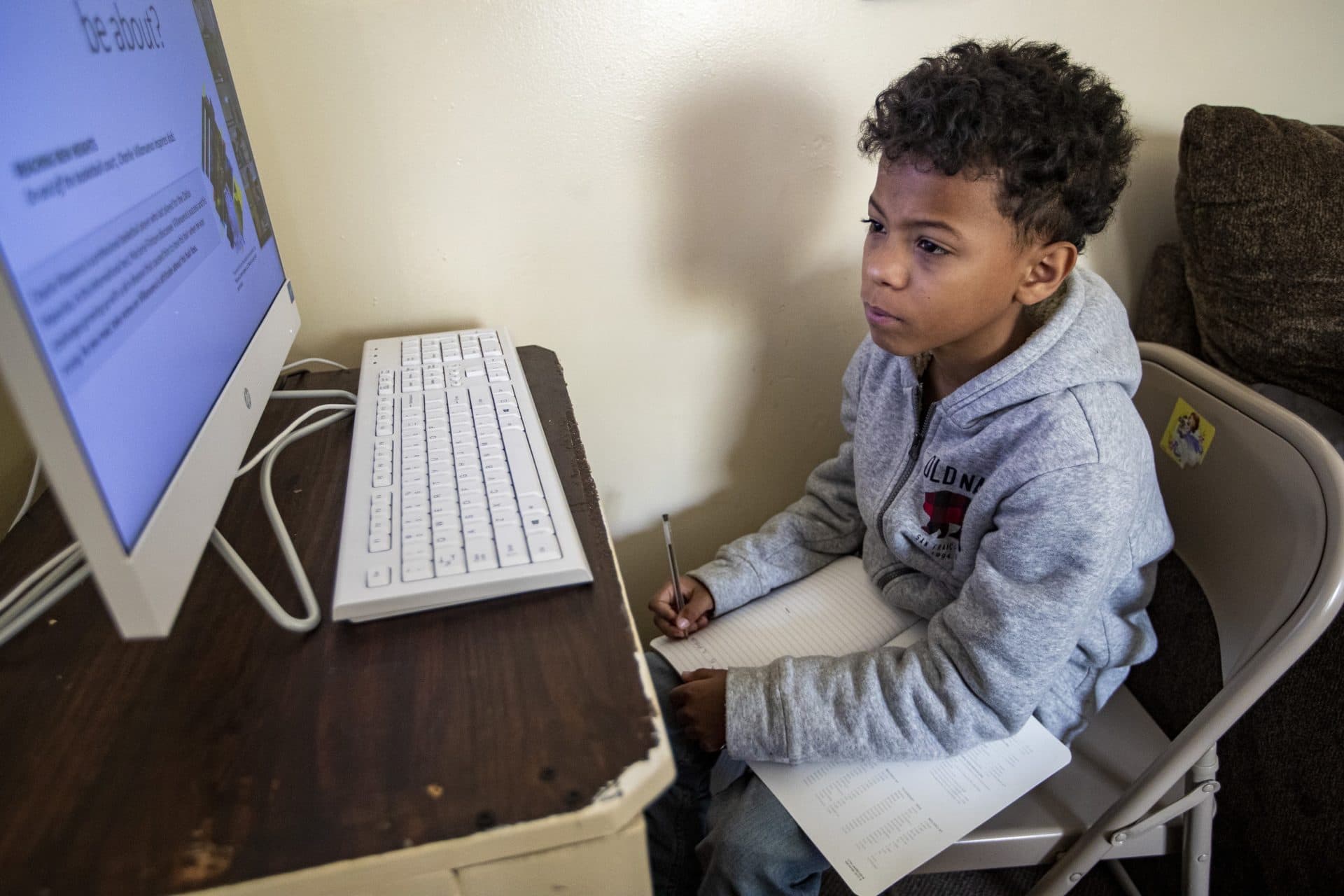

After breakfast, 10-year-old Jesus is shifting around in his chair in front of a computer in his living room. He’s taking his once-a-day, hour-long class. Today it’s math, and the teacher is describing geometric concepts to about 20 students, struggling to address technical issues as she goes. A Spanish speaking aide is helping the bilingual students.

Jesus likes to raise his hand and participate, but he’s already aware of the setback he's experiencing.

"I don’t learn as much here as I do physically in school," he says. "Because the lessons take sometimes 30 minutes, sometimes one hour, and school is eight hours."

Jesus is among the 14,000 students in Lawrence public schools who, like children across the state, have had to transition to remote learning over the last months. With some districts better-equipped than others — and some families better positioned to adapt to the change — experts say the rapid shift to remote education will worsen the existing inequalities between students of different backgrounds, and districts with different levels of resources.

They say the pain will be felt most in some of the state’s poorest communities, like Lawrence, which is also one of the cities hardest hit by the pandemic.

"Since we went to remote learning, there has been almost zero progress made because they're not engaging with teachers or content in a meaningful way,” says Theresa English, a history teacher at Lawrence High School.

She estimates about a quarter of her students have not been engaged since the transition to remote learning began in March. The reasons are multiple: students have trouble accessing classes online, they often share computers with siblings, and many parents don’t speak English or have the time to dedicate to helping kids stay on track.

“A large percentage of my students, probably close to half, are working jobs now,” English says. "Some of them even have second job. And school is not their first priority."

This situation could lead to the biggest educational setback of the century, warns Fernando Reimers, a professor of global education at Harvard and a former member of the state education board.

"There will be children who will never finish high school because of this,” he says. "There will be children who will never go to college because of this. There will be people who will have lower-paying jobs than they would have had otherwise.”

That's a setback Lawrence can’t afford. Because of consistently low academic performance, the district has been under state oversight for the last eight years. And many worry that any progress in closing the achievement gap will vanish because of the pandemic.

It’s hard to gauge how much students are learning right now. There’s no state standard to measure student participation in remote learning — each district is collecting the data in its own way. And Lawrence is among the districts not tracking this at all.

Superintendent Cynthia Paris says it’s hard to understand the whole picture in the midst of the shift to remote education, and with teachers using a variety of platforms that the district can’t necessarily gather data from.

"So if we were to say ... hard numbers, that's very tricky for us because the priority has been engagement across various platforms,” Paris says.

WBUR and El Planeta requested engagement data from the 13 largest districts in Massachusetts. Only three provided numbers. All were incomplete.

In Boston Public Schools: one in five students had not logged into official class last month. In Fall River, the district knows most students are using their computers, but not what students are doing.

Education professor Fernando Reimers this absence of data will make it hard to evaluate the shift to remote education.

“Denying that research is like putting blinders — it's deciding, 'I don't want to know.' And I don't see how you can navigate yourself through these crisis without a compass."

Data or not, the impact of the coronavirus epidemic on education in struggling districts won’t be fully understood until it’s over.

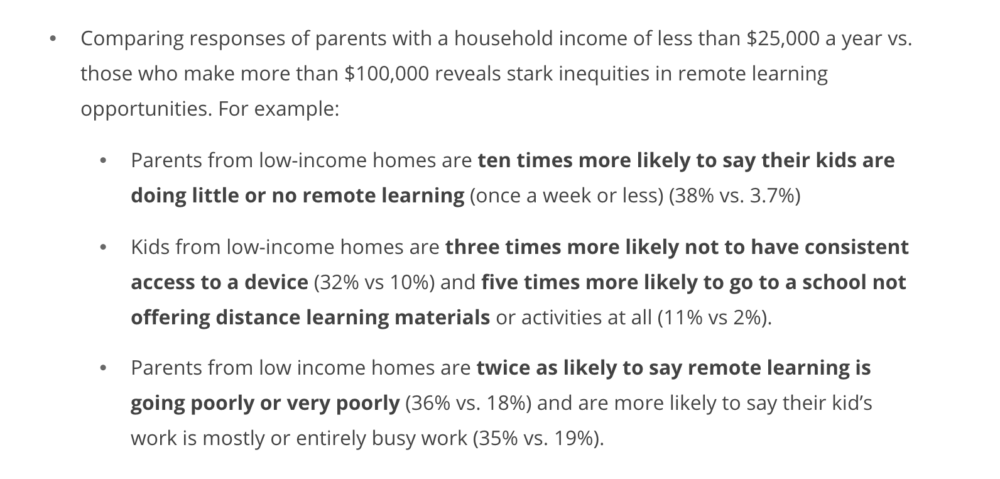

But a recent analysis by the advocacy group ParentsTogether Action finds "huge disparities in the success of remote learning depending on family income,” concluding that wealthier students are logging in twice as often as other students. And 40% of the poorest students are accessing remote learning as little as once a week or less — the same is true for less than 4% of wealthier students.

For families making more than $100,000 a year, the survey finds, 83% of kids are engaged every day.

Back in Lawrence, Margareth Jesus gets her kids ready to visit family in Beverly.

But the kids father is still in poor health, and Margaret fears he could have a relapse and that could mean having to send her kids to the Dominican Republic.

Officials in Lawrence say the pandemic has already caused many families to leave the city and the country — and with the coming school year still uncertain, it's unclear whether, and if, all of the students will return.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story listed the wrong name for Lucero. We regret the error.

This article was originally published on June 15, 2020.

This segment aired on June 15, 2020.