Advertisement

One-Year Pause In Exam-School Tests Sparks Hope — And Hostility

Resume

UPDATE: The Boston School Committee voted early Thursday morning to suspend the entrance test for the city's three exam schools for one year. The decision drops the admissions test for the incoming class next fall.

Boston's school committee will vote on a plan to suspend the test requirement to gain admission to the city's three prestigious exam schools Wednesday night.

Earlier this month, district officials presented the measure as a sensible response to pandemic conditions, and stressed that it would only apply to the next admissions cycle.

Still, the prospect has spurred families, alumni and staff across Greater Boston to discuss the exam schools' reputations for exclusion as well as excellence, and to debate the role they should play in a changing city.

As both an educator and exam school alumnus, José Valenzuela was glad to see Boston walk away from the ISEE, its longstanding entrance exam, back in February.

"It was not really a great indicator of whether a student can do exam-school work," said Valenzuela, now a teacher at Boston Latin Academy. "I don't think it really indicates anything."

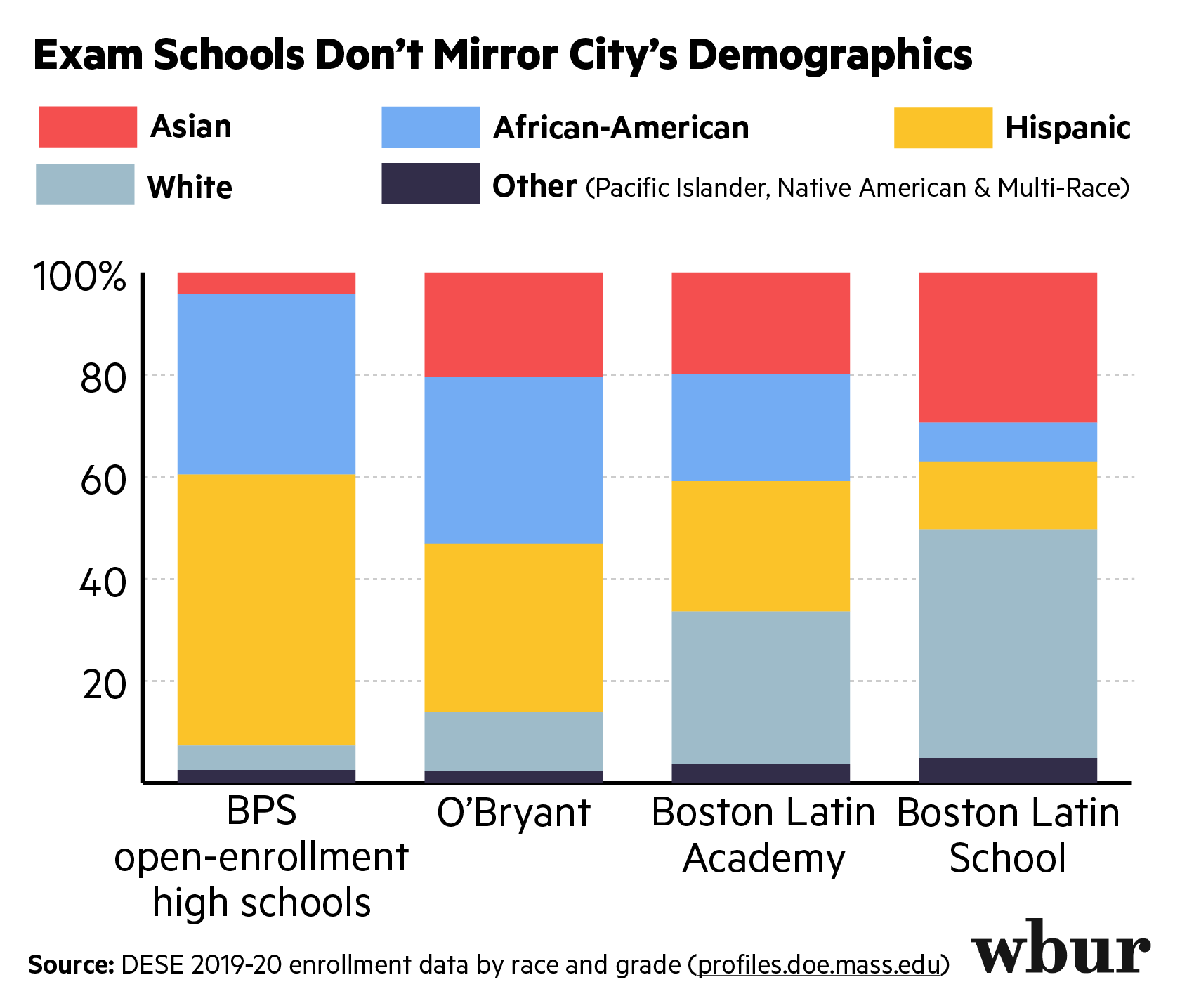

The test played a role in the demographic drift of all three exam schools — and the Boston Latin School in particular — away from the city at large.

One telling datapoint: there are about 2,500 white students enrolled at the nearly three dozen BPS schools that educate students through the 12th grade. Nearly 72% of them attend one of the three exam schools — including 43.7% at BLS alone.

Valenzuela supports the proposed suspension of the test — in part, because it promises to reverse a trend that started when he himself took it.

Born in the Dominican Republic and raised in Forest Hills, Valenzuela came to Boston Latin School in 1997. It was just as the school's historic practice of setting aside 35% of seats for underrepresented minorities was falling apart in federal court.

Black and Latino students held about one in three seats at Boston Latin when Valenzuela entered. By the time he graduated in 2003, it had dropped to nearly one in six.

"I basically saw, over the six years I was there, the precipitous decline of people of color at the school," he said. And it wasn't pleasant for those that remained.

“That was always sort of a hanging question about my attendance at the school. Like, did I really deserve it, or did I just get in because of a quota?”

Wrestling and music kept Valenzuela enrolled, if not at ease. But he said it wasn't until he was at Williams College (on a large scholarship) that he discovered that he "liked learning" again.

Valenzuela's experience evokes the 2016 "#BlackAtBLS" campaign, led by two students fed up with racial hostility at the elite school. It hits home for older alumni, too.

"So many stories," said Norma Rey-Alicea, a 1993 graduate, raised in Jamaica Plain. A guidance counselor told her she was "too poor" to go to a particular college. A white classmate called her an affirmative-action case when she got in somewhere he didn't. Another teacher often said "girls don't belong at the Latin School" (it only went co-ed in 1972).

The quota system was still in effect when Rey-Alicea — who now runs an education nonprofit — came to BLS. She credits her mother with helping secure her seat: she was engaged in her community, liked the idea of the classics and tracked down some free test prep.

Rey-Alicea too supports the proposed pause in the testing regime. But she added that diverse admissions is only a start.

"There's so much debate around getting people in," Rey-Alicea said. "When I was there, at least half of my classmates of color dropped out. It’s not just about getting in, it’s about finishing."

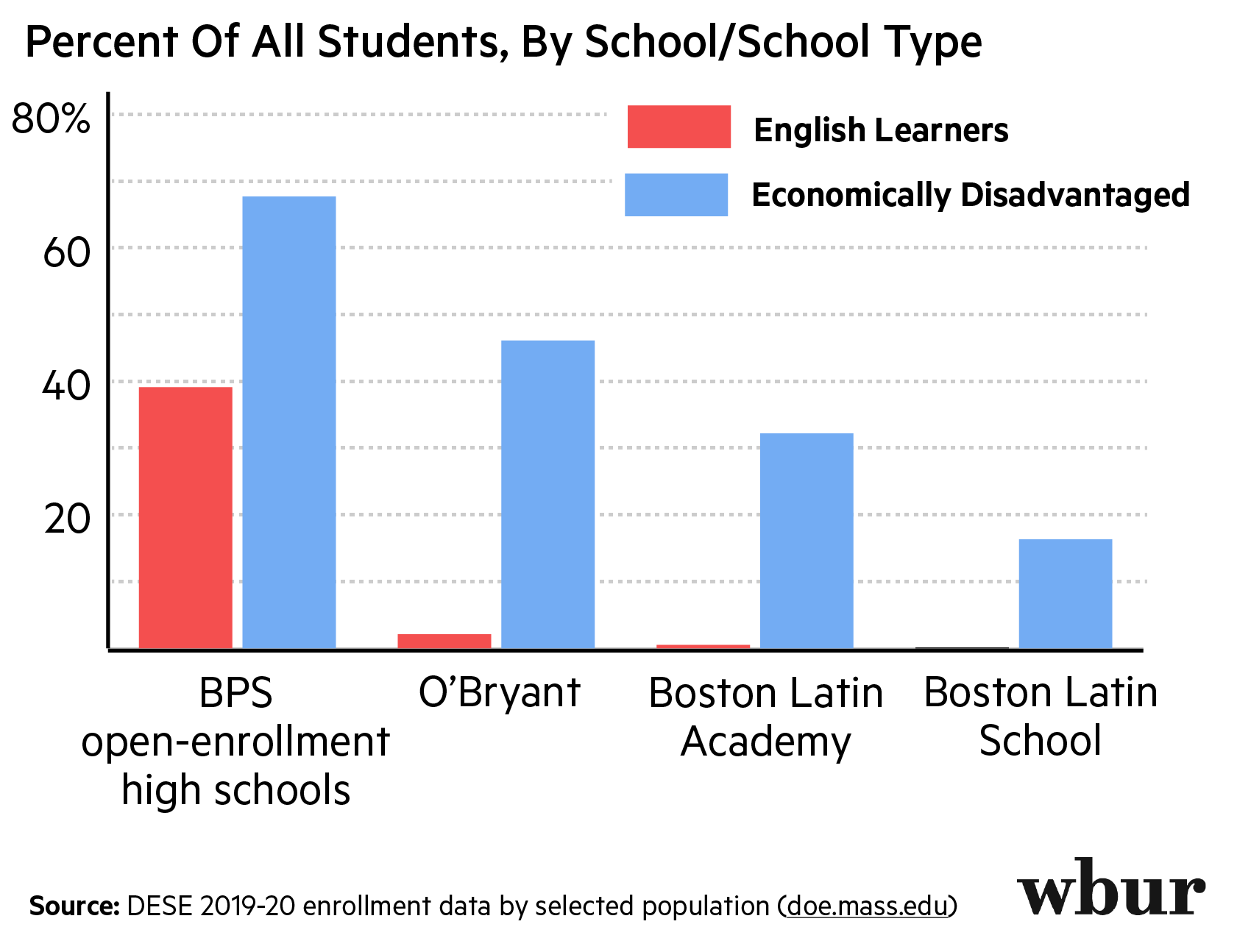

If the plan before the Boston School Committee Wednesday night passes — and works as projected — as many as hundreds more Black and Latino students could receive invitations into exam schools next year. But the task of supporting them would not be the only cost.

Like white students, Asian-American students have tended to do well in the quest for an exam-school seat since 1998, albeit by smaller margins.

The interim system would sort students and apportion seats, in part, based on their home ZIP code. Some families worry this system will overlook the students or the financial need in Chinatown, due to its small size and rapid gentrification.

City Councilor Ed Flynn, who represents Chinatown, raised some of those concerns during an information session Monday night.

Go Sasaki has heard them, too. Sasaki took a teaching job at the O'Bryant School of Math and Science this year, in part to work with the large cohort of Asian-American students there.

"A lot of our families that are immigrants — they come from countries where there is a big exam," Sasaki said. For many, there's a sense that "an exam school is the only chance for them to get a good education for their children.”

As the product of Silicon Valley school districts where schools were both open and well-regarded, Boston's exam schools still strike him as a frustrating zero-sum game.

"No matter what they do, there are always gonna be people that have more opportunity than others," Sasaki said.

If the change is approved Wednesday night, the district will embark down a difficult road. Students and families of all kinds will have to take a chance on something new and at least a little risky. Staff will hope to improve on the historical record when it comes to supporting and retaining low-income students of color in their classrooms.

And the district will have to develop a permanent admissions regime for 2022 and beyond that can withstand likely legal and political challenges on multiple fronts. (That regime will, the district has said, rely in part on a new untimed test — the NWEA MAP test — but seems likely also to use grades and demographic data to look beyond the top scorers.)

Valenzuela said he knows that work will be slow and uncertain. Then again, it's what brought him back to the cloistered world of Boston's exam schools after painful years as a student.

"I wanted kids at BLA to have experiences different than what I had," he said. "I wanted to be part of that change."

This article was originally published on October 21, 2020.

This segment aired on October 21, 2020.