Advertisement

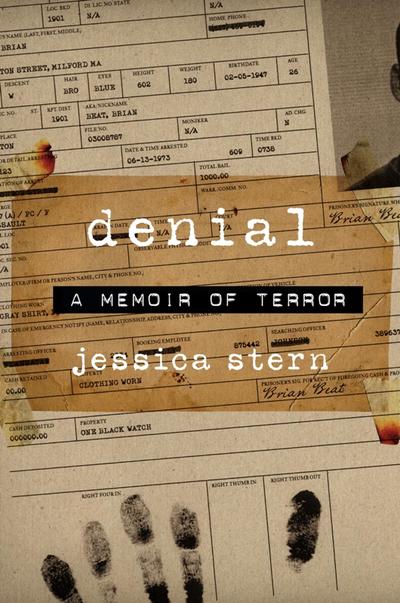

Book Excerpt: 'Denial: A Memoir Of Terror'

Jessica Stern is an internationally renowned expert on terrorism, but in her latest book, she explores the time that she and her sister were raped in Concord, Massachusetts when they were in their teens. She writes about the denial of the local police, her father and herself after the crime. Decades later Jessica investigated the crime and found out that her rapist had been responsible for more than forty other rapes and attempted rapes in the Boston area. We speak to Jessica about her book "Denial: A Memoir of Terror," excerpted below. We also hear from Amy Vorenberg, who was also raped by Jessica's attacker.

Jessica Stern is an internationally renowned expert on terrorism, but in her latest book, she explores the time that she and her sister were raped in Concord, Massachusetts when they were in their teens. She writes about the denial of the local police, her father and herself after the crime. Decades later Jessica investigated the crime and found out that her rapist had been responsible for more than forty other rapes and attempted rapes in the Boston area. We speak to Jessica about her book "Denial: A Memoir of Terror," excerpted below. We also hear from Amy Vorenberg, who was also raped by Jessica's attacker.

Note: The following excerpt contains graphic content and may not be appropriate for everyone

Chapter 1

I know that I was raped. But here is the odd thing. If my sister had not been not raped, too, if she didn’t remember— if I didn’t have this police report right in front of me on my desk—I might doubt that the rape occurred. The memory feels a bit like a dream. It has hazy edges. Are there aspects of what I think I recall that I might have made up?

In the fall of 2006, I got a call from the police. Lt. Paul Macone, deputy chief of the police department in Concord, Massachu¬setts, called to tell me he wanted to reopen our rape case. “I need to know if you have any objection. And I will need your help,” he said. The rape occurred in 1973.

Lt. Macone and I grew up in the same town, Concord, Massa¬chusetts, considered by many to be the birthplace of our nation. It is the site of the “shot heard round the world,” Ralph Waldo Em¬erson’s phrase for the first shot in the first battle of the American Revolution, which took place on the Old North Bridge on April 19, 1775. The town is frequently flooded with tourists, who come to see the pretty, historic village and the homes of Bronson and Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, who lived and worked there. It is still a small town, with small-town crimes. The Concord Journal still reports accidents involving sheep and cows.

Although we didn’t know each other, Lt. Macone and I overlapped in high school. We never met back then; he was a “motor head,” as he puts it, obsessed with cars, and I ran with an artier crowd. But I knew the name—everyone in town did—because of Macone’s Sporting Goods. Everyone bought sports equipment there. It was a fixture in our town. It’s where I bought my bike, the bike I was riding home from ballet class on the day I was raped.

I had recently requested the complete file. I wanted to understand what happened to me on the day that my sister and I were raped. I had an idea that by reading the file, by seeing the crime reports in black and white on a page, I could restore a kind of order in my mind. If I could just connect fact with feeling, the fuzziness in my head would be reduced, or so I hoped.

The file had to be redacted. Lt. Macone had to read the entire file in order to black out the names of suspects and other victims.

He told me, “I read that file from cover to cover. And I realized that the rapist might still be out there. There were other rapes. The same gun, the same MO—what if the rapist were still on the street? Other children could be at risk. I was worried about what might happen if the rapist were still at large.”

Lt. Macone brought the case to his boss, the chief of police. “I’ve been a cop so long, we can’t help trying to solve crimes. Twenty-nine years on the force. And I thought this crime was highly solvable. You’d have to be brain-dead not to see that. There was the unusual MO. The fact that you and your sister both saw the perp’s face before he put on his mask. There was a description of the gun, of the perp’s clothing. The fact that he spent so much time in your house, early in the evening, when all the neighbors were home. To say that it piqued my curiosity is an understatement.

“It was clear to us what had to be done,” Lt. Macone said. “We had to try to solve the crime. But we knew we would need your help. I needed to ask questions that could be quite personal. I didn’t know if it could put you over the edge. . . . I didn’t want to be a party to revictimizing someone. You seemed like you wanted to know . . . you seemed sincere. . . . But I needed your help to go forward. Not every rape victim wants to revisit the crime,” he said.

But I was willing.

In the police station in Concord, files are kept in a locked room on the second floor. To get there, someone has to release the lock on the elevator, and someone has to let you into the locked room. Every time I’m near that room, I feel cold. There is a single file cabinet containing sexual assaults. One of those old-fashioned gunmetal gray cabinets. I hate those. The same kind my physician grandfather kept his X-rays in. The Concord PD keeps the records of certain crimes for a specified number of years, and the records of other crimes forever. The “forever” crimes include violent sexual assaults.

In the forever-crimes file cabinet, a couple inches back, was another fat file, another cold case. There had been a rape, two years before ours, right around the corner from where our rape occurred. “I was astounded,” Lt. Macone told me. “There were two victims, just like your case. The same kind of gun. The perp sounded remarkably similar. Unless I was missing something, this was clearly the same guy.

“We get a lot of record requests,” he said. “But this one was very unusual,” he said. “This was the most serious crime I’ve seen in my twenty-nine years on the force.”

“What was so unusual about the crime?” I asked. I had always heard that rape was a relatively common occurrence, so I was surprised.

“Everything,” he said. “There are very few stranger rapes in Concord. We get indecent A and B’s [assault and batteries], but very few crimes involving firearms. And very few cases involving home invasions, especially with kids involved. Every horrible factor you could have was there,” he said.

It was almost impossible for him to imagine, he said, that a crime like this could occur in his hometown. It is almost impossible for me to imagine that Lt. Macone and I grew up together. Lt. Macone grew up in a safe town, a town where the few crimes that occurred would certainly be solved. I didn’t.

Lt. Macone saw that the detectives who worked on the case in 1973 did not take the crime seriously, in part because they did not believe my sister and me. They had trouble believing that the rapist was a stranger to us. Rapes like the one we described simply did not occur in our town, or so they believed. Denial and disbelief were the easier course. The detectives left notes such as the following: “I told Mr. Stern that I feel the girls were holding something back from us,” and “I was sure that this person may have been there longer in the house [than the girls reported to us].” On the back of one of the statements taken from me several days after the rape, I found a detective’s handwritten note recording my reaction. “She says she sees she has a ‘skill’—becoming very stern and hard.” This was a clue, I would later discover, that I had already been traumatized. But how?

In notes from February 13, 1974, four months after the crime, I see: “Personal visit. Spoke to Mr. Stern. He states nothing new to add. He feels that both girls seem to have forgotten it.” The police took my father’s statement as permission to cease investigating the crime, and the rapist was not found.

I see in the files given to me by the Concord police a laboratory report from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. A doctor examined us, I remember, in the hospital. It was dark by the time we got there, and the hospital was empty. I remember bright lights shining on my body and in my eyes, like a crime scene in a dream. In the dream, someone had accidentally transferred my soul to someone else’s body for the evening. My sister Sara was in the hospital, too. But she must have been down the hall because I couldn’t hear her voice. I felt alone. It was a time of night when we should have been in bed at our father’s house, the beds my father had made for us. I wanted to say, “There has been an error here. This is me, Jessica. I am not a grown-up! I should not be alone here. I am not a criminal!” But I was stuck in the dream. I couldn’t escape. I heard that buzzing sound of fluorescent lights. The sensation of cold when the speculum pierced, once again, the flesh that felt torn.

Would I ever heal? No, I would not. I would become someone else.

The laboratory reports indicate that sperm were detected in my underpants, my leotard, and my jeans. I do not recall whether they found sperm on my body, but they must have. How much of what I think I recall is correct? How much of it is a result of memory distorted by the Valium and sleeping pills the doctors administered to us afterward, or the chemicals my body produced, the chemicals that even now are distorting my features as I read the file, making me hard and tough?

How much of what we think of as an admirable response to trauma—the “stiff upper lip”—is actually disassociation, the mind’s attempt to protect us from experiences that are too painful to digest? I can recall the facts, at least some of them. But I don’t feel very much. At least, the feelings I have are not kind. They are not sympathetic toward my fifteen-year-old self. It happened. It happens to a lot of women. I survived. Most women do. I am “strong,” but in those moments of strength, I don’t feel.

I will admit that I am very afraid of one thing. Not just afraid. Ashamed. I am afraid that I am incapable of love.

This is not the first time I have read my police file. In 1994, when one of my neighbors thought she might have been sexually abused, it occurred to me that our rapist might have raped her, too. I asked the police for my then-twenty-year-old file, and they sent me part of it, including a barely audible audiotape. Even now, I haven’t found the courage to listen to it. There was nothing in the file to help my neighbor, and nothing in the file that helped me, at least not then.

The first time I saw the file, it was incomplete. But now I have the whole thing. Everything is here—the things we had to tell the police, the things the police wrote down that they thought about us at the time. Only the names of suspects are blacked out.

I have trouble reading it. The copy is bad, but that is really just an excuse. I have trouble focusing my mind, as if my brain were underwater. I have an urge to put it away. I force myself to read. Moments later I want to stop again. Again, I force myself to read.

A wave of loneliness washes over me as I read. I felt so alone as a child. Our mother had died when I was three years old and my sister was two. We lived with our grandparents while my mother was dying, and stayed with them, after that, for a year. We moved out when my father remarried, a little over a year after our mother’s death. He married Lisa, the older sister of my best friend in nursery school. The marriage had been more or less arranged by my best friend’s mother and my grandmother. It was as if our father had married Mary Poppins. Lisa was young and bright and impossibly beautiful. I can still recall the comfort of resting my cheek against the smooth brown skin of her forearm. But it was not a good marriage. It lasted only six years. When I was twelve, our father married for the third time.

Our father was in Norway with his new wife at the time we were raped. I remember this distinctly. That is why a babysitter was staying with us. She was supposed to be ferrying us around. The evening of the rape we had gone to Lisa’s house, as we did, once a week, after ballet. But Lisa went out to dinner that night, taking our half sisters with her. My sister and I stayed behind. We had homework. We asked the babysitter to pick us up. She was busy, she told us. I remember this. And I remember what I see here in the notes taken down by the police at the time: the babysitter didn’t believe us when we called again a couple hours later, immediately after the rape, telling her that now she really needed to come get us. It was too hard to believe, in 1973, that girls could be raped in Concord, Massachusetts.

Our father was visiting the Trondheim Institute of Technology. I know because he told me this. And I remember. He was establishing what he considered to be a very important relationship for his laboratory. They would cooperate on radar technologies. But here is something I learn upon reading the file for the first time, something that, amazingly, I did not recall. When our family physician called our father to tell him his two girls had been raped at gunpoint, he did not curtail his trip. He did not come home to us right away. How is it that I keep forgetting this fact?

My father is a remarkable man. He is immensely strong. You can see his strength in the line of his jaw, his erect posture. If you met him, you would probably come to love and admire him. Nearly everyone does. You would sense an old-fashioned kind of integrity in him, an integrity based, in part, on the power of will.

I am proud of my father. He is like a precious jewel that has been handed down in my family. But he has sharp edges. Sharp edges, yes—but there is another side of him. He is wonderful with children. He lets them push themselves. He knows my son is agile and strong, so he let him climb on the roof of his garage from the time he was six years old. He would not let other, less strong children do that, my father tells me, and I believe him. I will admit that I feel slightly frightened when I see my son climbing on this roof, but I still my fear. I do not want to overprotect my son.

I suppose my father must have felt me to be tough, like my son. I know my father loves me very much, but sometimes the jewel-hard side is the one he displays, perhaps to protect the more tender side. I believe that my father is unbearably tender inside, but my belief is based more on faith than evidence.

My father invented many things, mostly related to surface-wave devices. He invented a flat-panel display. He and two other physicists invented X-ray lithography, a technology that makes it possible to lay X-ray-absorbing metals, such as gold or tungsten, onto a chip made of diamond or silicon. X-rays are what killed my mother. If only X-ray-absorbing metals had been placed on my mother’s body when my grandfather irradiated her. But in those days the dangers of X-rays weren’t fully understood, and my mother died.

There are items in the file that I find impossible to believe. For example, I told the police that someone—perhaps the rapist— called me at my father’s house a few days after the rape, calling himself “Kevin Armadillo,” identifying himself as “the one who fucked you last night.” How could the rapist know to find me at my father’s house? He did not rape us there, but at our first stepmother’s home. How would he have known that we lived with our father, and were only visiting our first stepmother? I am mortified. I don’t recall any such thing. Was I in a state of hysteria, making things up in order to get attention?

I also reported to the police that someone had left a handwritten poem in my bedroom, soon after the rape. I see in the file that the police questioned my father. He, too, had a hard time believing me. How would a person get a poem into the house without being noticed? How would he know when it would be safe to stop by our house, walk up to my bedroom? How could he know when no one would be home? Neither my father nor the police believed this strange story then, and I don’t believe it now. I see what I told the police and feel ashamed. Why would I lie to the police?

But in the back of the file, I find the poem. Here it is:

Out

In

Out your window (or mine)

Flies an aged child

Who often lives from only a few seconds

But other times may become great and mighty

Strive with this flier

Its course is true to its laws and design

And note carefully: once it passes you,

It is gone; yet it has cooled and refreshed

This gentle wise flier is merely a zephyr

—a cool refreshing breeze

—a passing encounter

Touch and reflect off of and upon what

you touch

Leave behind the past

Steer carefully only for the immediate future

Be here now.

Trauma of the past must be understood as

Not being here now or it becomes trauma

of the present.

How could I have forgotten this poem? I do not know what to make of it.

I do remember the fact that I was raped. I can force myself to recall certain details. The fact that we thought he was joking when he told us he had a gun. We thought he was joking until he threatened to kill us. The fact, missing, for some reason, from the written record, that he asked us to show him where the knives were kept.

The police asked my sister and me to write down what had occurred. We did this, the report states, between 11:30 pm and 1:45 am. Those words are before me now. I read the words I know I wrote, in a penmanship I barely recognize. My notes from 1973 are written in italics below.

—sitting doing homework

—man walked in

The penmanship looks alien. I don’t recognize the persona captured in these words, the writing slanting backward, the letters round, fat. Was I ever this feminine?

I try to imagine “man walked in.” I feel a kind of chemical strength. Not fear, not sadness, but a chemical agitation.

—showed us gun, don’t scream

Reading these words, I feel a jarring in me, something quite hard and harsh forming in my veins, as if my blood were forming shards. This is a familiar feeling. I become a soldier if I am truly threatened. If the plane goes down, you want me at the controls.

Here is what I think now, reading what I wrote down for the police at age fifteen, right after I was raped. I was a good girl. Always a good girl, even when I was bad. I did my homework.

If I can only be good enough, someone will eventually notice that I am trying so hard, exhausting myself with my effort to be good. This is true even today.

I knew what good means. Good means never revealing fear. Good means not complaining about things that can’t be changed, like the presence of a strange gunman in the house instructing me not to scream. Of course I won’t scream, I didn’t scream then, I won’t scream now, certainly not out of fear or the thought of my own pain. I was not one of those hysterical girls who flinches or screams in the face of “man walked in” or “showed us gun.” I knew that if I were bad, if I revealed my terror, he would kill me. I already knew how to absorb fear into my body—my own and others’—to project a state of utter calm and courage.

—said look down

Of course I looked down, not at his face. I understood the simple bargain: no looking, no flinching, no sudden movements, stay alive. Looking where he said to look.

What terror would I have seen in his face? I would have drowned in a sea of fear.

—he’d only be 5 min or 10, wouldn’t hurt us

—was anyone home? When would they be home? Be quiet.

Would kill us if we uttered a word

Well, that is easy, only five or ten. If anyone else were home, they might not have known how to handle this man. But I did. Be quiet, he said. If you say anything, he said, I will kill you.

I was quiet.

—made us go upstairs looking down, quiet dog

My sister remembers this expedition, the three of us walking single file, up the narrow flight of stairs, his gun to our backs. “I thought we were being marched to our execution,” she recalls. “I was trying to telegraph to you to be quiet. My biggest fear was that you wouldn’t comply and that you would get killed.” Why was my sister afraid that I would be the one killed?

In any case, I did comply. I floated into docility.

—close shades

The shades hiding our shame.

—take off pants. Asked if we’d still be clothed

The pants covering our shameful spots. The vulnerable spots now exposed. Would we still be clothed? We were wearing leotards. But I know the answer to that question now: I would never be clothed again.

—take off leotards.

We had ridden our bikes home from ballet class, jeans over our leotards. We were unspoiled and tough, unlike other girls, the kind whose parents might have driven them across town, the kind who might have screamed.

But now skin is revealed, legs exposed to cold air. Still, I did not scream.

—facedown on bed

I recall thinking that if I did what he said, we would stay alive. Don’t scream, don’t protest. I cannot recall the sensation of facedown on bed. Did the blanket scratch the cheeks and mouth, the mouth that would be good, that would not scream? Did the blankets comfort, did they suffocate?

—made us brush each other’s hair

—made us try on little sister’s dresses

—too small

—made us put on stepmother’s dresses

—made us take off dresses

—told us to lie facedown

—made us sit up

How did those dresses feel on the skin that no longer seemed like mine, the “I” that I no longer know? Did I know that soon after putting on a dress, I would have to take it off?

I do recall “man walked in”: I can see a kind of apparition in my mind’s eye. I do recall the threat to kill us if we spoke. But now I am lost. My mind cannot focus. An apparition of cold flits across my heart but is gone so soon I wonder if I imagined it. I am annoyed with this little girl whom I’m struggling to hold in my mind’s eye, who wants me to understand how she suffered. You will be fine, I want to tell her. I feel anger at her, even more than “man walked in.” I do not want to hear about her fear or her pain. It wasn’t that bad.

—stroke and lick penis

—said he put gun down

—said he could reach for it at any time

Now I begin to feel something new. A foggy nausea takes hold, leaving no room for thoughts or action. Why didn’t I bite hard? Would it have been worth it to hurt this man, even if he killed me? Did I have the strength in my jaw to bite? I think not. I was in a sea of nothingness.

—sit with legs spread

Who spread those legs? How vulnerable I feel, thinking of this girl, her legs spread wide, exposed to this “man walked in,” exposed to an evil cold.

—asked us what we called vaginas.

—we said crotches.

—he put his finger up me

—had we heard of cunt?

Yes.

—entered me while I was sitting.

—told me it didn’t hurt

—he was sterile and clean. Two times.

—I said it hurt

—he said it didn’t.

I do remember the hurt, as if someone had inserted a gun made of granite that scraped my flesh raw, at first scratching, then tearing, then scraping the flesh off bone, leaving the bone sterilized by pain.

I am hollow and sterilized now. Not long after the rape, I lost my ability to urinate. I had to be catheterized, and later hospitalized. I began to walk with crotch held back to prevent intruders, muscles so tight I have to will myself to urinate, sometimes even now.

Now he turned his attention to my little sister.

—tried to rape my sister Sara

—I told him not to, please.

How did I find the strength to talk? I was spellbound by the potential for death contained in that gun, entranced into a statuelike calm. An animal intelligence had taken over where an “I” once held at least the illusion of dominion, where thoughts and action were once connected. The “I” was lured away into a space of infinite white, a space of no feeling other than calm, far from the human world, entranced into leaving its normal home—my body—by this man’s insistence that he would kill me if I spoke. The animal mind that took over when the “I” had gone ordered the body that remained behind to be passive, silent, and calm, knowing, in its animal way, that compliance was required to keep the body alive.

But now there was something more important than sustaining the life of that body, something that knocked that shameless and shameful animal-mind back to its rightful place, a place I know nothing of, that I want to know nothing of, in this life. My little sister’s pain pulled me out of my trance, and an “I” returned, determined to protect her; but I don’t believe that the “I” that came back was the same “I” that my body had housed before. The new self that emerged was like a baby, having never been exposed to the world. The world felt new to me, baby that I was, more penetrated by sound. The sounds that had once thrilled me with feeling now grated on my ear. I had been playing Bach’s third French Suite, Debussy’s “Engulfed Cathedral,” and Beethoven’s Pathétique before the hour the rapist spent playing with our lives, perhaps, so we thought, planning to kill us when he was finished with us. Where I once heard—in my mind’s ear—a cathedral rising from a Turner-like mist, I now heard scrapes and moans rising from the piano keys under my fingers when I played. I have trouble forcing my eye back to the page where I wrote the actions performed on me and by me during that very long hour.

—tried to rape my sister Sara

—I told him not to—please

—stood up. Told me to stand. Picked me up. Entered me telling me to wrap my legs around him.

Was he just a broken boy, needing someone to wrap her legs around him? This thought nauseates me again. A broken boy, stabbing and piercing a broken girl, leaving her shattered, as he was shattered. Why did I perceive him as broken even then, before I knew anything about him, before I knew anything about violence?

—faces down on bed

—told us it would make us angry

I remember what happened next: the click of his gun. I thought he was cocking it, preparing to kill. I was calm again, entranced into complying with his murderous plans.

Here is what shames me to the core: I thought he was going to kill me, but I did not fight him. I was hypnotized into passivity. I had no strength to run, and anyway I did not like the idea of being shot from behind. It seemed easier just to wait until the murder was done with.

There was no sex in that room. No love. But there was a seduction. The seduction of death.

Would he kill just one of us, making the other angry? Would he kill both of us, imagining that we would be angry at him in heaven, after our deaths? Why didn’t I get up? Why remain “facedown on bed”? Why did I not rise up, Medusa-like, eyes flashing, the snakes in my hair ready to strike him dead? Why did I not overpower the puny little man, smack that gun out of his paltry, worm-white fingers? I was strong then, probably stronger than he, certainly very strong now.

And then he explained to us that the gun was not real, it was a cap gun.

—it was a cap gun.

I wrote dutifully, always dutiful. After complying with the rapist I complied with the police. Was this the most embarrassing part—that I had been entranced by the thought of a gun? That my fear, unfelt even as it was, had hypnotized me into complying with a person, if he was indeed a person and not an apparition, wielding a child’s toy, not an instrument of death?

—he said don’t call police. I promised I wouldn’t.

—it would make us in more trouble.

—he left. We heard car.

I remember this part, too. I told Sara he was right; we shouldn’t call the police. Somehow, even then, I felt him as a victim. I told her that they would put him in prison, that prison would not reform him: it would make him worse.

After he left, I saw in my mind’s eye the image of a broken man, more broken still by the violence he would encounter behind bars, emerging as a true monster, a rapist who would actually kill his victims rather than leave them only half dead. It may be, I know now, that this intuition was correct. Was this a kind of Stockholm syndrome? Does it happen that fast, in the space of an hour?

Sara was more afraid than I, but also more alive. She retained a human-like strength in her arms and hands and mind that I now lacked. She insisted. She picked up the phone. No dial tone. He had cut the wires. He had cut the wires in the basement, a big puzzle. How would a rapist have time to cut the phone wires or know where to find them in the dark, dank basement? How long had he been in the house? How long had he been plotting this crime?

“He kept saying he wouldn’t hurt us. He kept saying to listen, to be quiet.”

I was quiet. I listened.

I’m still listening now. I hear a rush, in my mind’s inner ear, of insistence. A kind of aural premonition, but a kind of premonition that goes both backward and forward, the soundless protest of all the raped, shamed, and silenced women from the beginning to the end of time. “He hurt you, he altered you forever,” the chorus soundlessly insists, grating on my inner ear— the ear that wishes not to be reminded of feeling. I respond to that chorus: Hurt is not the right word for what that man—if he was a man and not an apparition—did to me. I feel a void. Something got cut out of me in that hour—my capacity for pain and fear were removed. The operation to remove those organs is indeed painful, as you might guess. But the surgeon cauterizes the cut, and feeling is dulled, even at the points where the surgeon’s knife entered the once-tender flesh. There is no more tender flesh. It’s quite liberating to have feeling removed, the fear and pain of life now dulled.

Nabokov once said, “Life is pain.” Buddhists, too, believe that to live is to crave and to crave is to feel pain. To live in this world involves pain. Had I not been catapulted, in that one hour, halfway to death, and therefore closer to enlightenment? In death we no longer feel human cravings, no longer feel human pain. I was now halfway there.

Later, of course, I would come to reject this understanding of what happened to me that day. Yes, I was partly released from the pain of being alive. But my spirit had traveled, not toward the infinite divinity of enlightenment, but toward the infinite nothingness of indifference. A soft blanket of numbness descended like snow from the heavens, obscuring and protecting me from terror. Instead of fear, I felt numb. Instead of sadness, I experienced a complete absence of hope. I would come to feel, in a very small way, the indifference of the Muselmänner, the Auschwitz slang for the prisoners who had lost all hope, who no longer fought to stay alive. A divine spark, the craving for life, had been extin¬guished in those prisoners, who were destined for death. Their hopelessness turned out to be a death sentence. The other prisoners knew, by the blankness in the eyes of the Muselmänner, that these prisoners—whom Primo Levi referred to as “the drowned”— would soon die. The still-living prisoners avoided “the drowned” like the plague, as if indifference were contagious.

They were right, of course. Indifference is a dangerous disease.

“He kept saying to listen, to be quiet.”

I have listened and I have been quiet all my life.

But now I will speak.

At the very bottom of the page, in a penmanship slanting ever more backward, I finally focused on what the police really wanted to know, the appearance of the apparition that had visited itself upon me.

—he smelled

—brown wool over face

—shorts, white socks

And then more detail.

—bobby socks, sneakers

—he was skinny

—light brown hair on legs

—strong cologne

—concord accent

It must have been hard to report the evidence of my senses—it came last, as if it were too painful to record anything other than the facts that transpired.

In the margin at the end of my statement, the police officer wrote what must have been my words to him at the time: “Forcing myself, determined to get it out.”

My sister’s statement reported the same facts, but her style is quite different from mine. She wrote in whole sentences, rather than lists. She began with how the rapist looked—his height, his socks, his sneakers. She remembered some things that I seem to have forgotten. That he made us lie down on the rug in the living room. That he had the woolen mask in his hand when he arrived. That we did not believe him at first when he said that he had a gun. She observed that he acted, throughout, as if he were teaching us.

After the rape, I fell into a perilous numbness, but fortunately, my sister took charge. Sara was petrified, but also determined to get help. She had the thought of walking out of the house into the cool night and going to use a pay phone on the street. So we did. That phone, too, was broken. We seemed to have entered a new, separate world where there was no way to communicate with the people we once knew.

Once again, Sara came up with a plan. We went to Friendly’s. There, finally, we found a phone that worked. We called the babysitter who was in charge of us while our father was away in Norway.

Yes, we had been visiting our first stepmother, Lisa, our father’s ex-wife. We visited Lisa, and our half sisters, every Monday night after ballet. But on that particular Monday night, October 1, 1973, she went out to dinner with our half sisters, leaving us behind to do our homework in an unlocked house in a safe neighborhood in a safe town, a town filled with good girls, though we were especially good. I was a good girl—I always did my homework, even when I was bad.

Copyright © 2010 by Jessica Stern. All rights reserved.