Advertisement

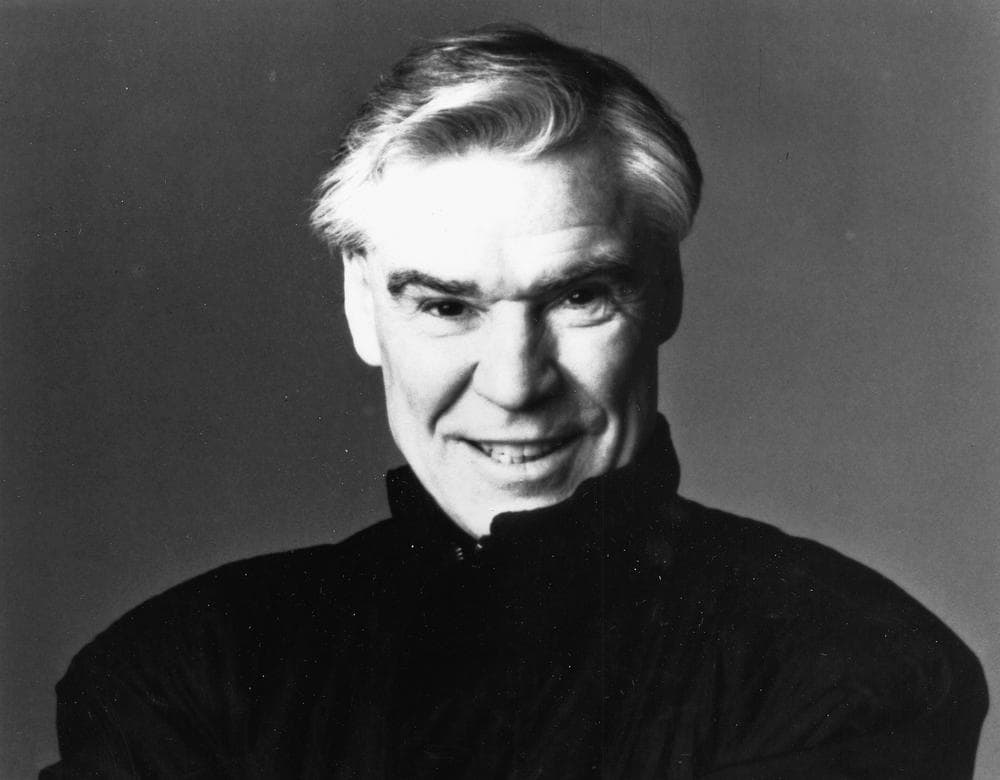

Dancer Jacques d’Amboise Describes 'How The Arts Can Change Lives'

Resume

The engaging and energetic 77-year-old Jacques d’Amboise, one of the great American ballet dancers of the 20th century, has published a memoir.

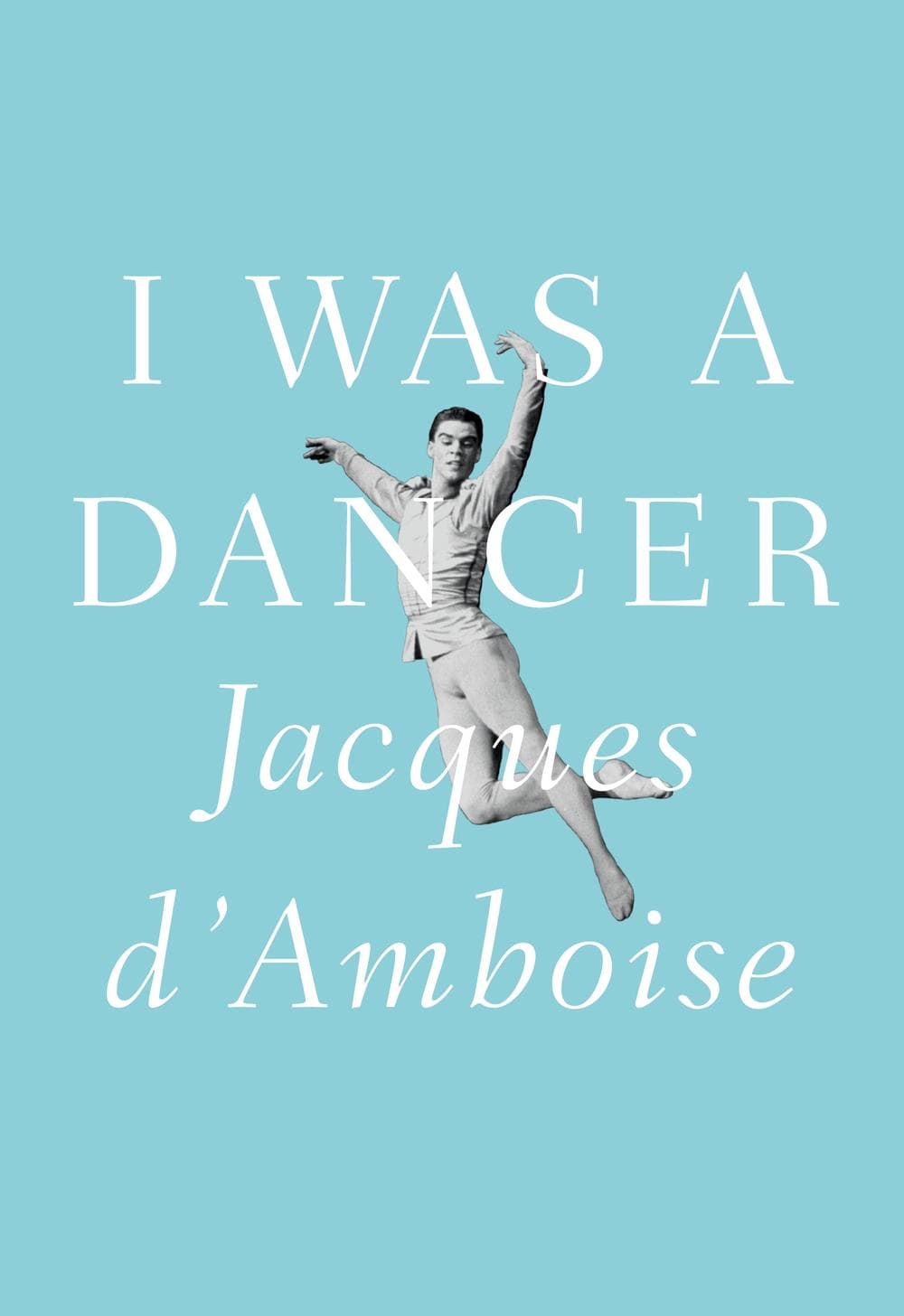

"Who am I?" he asks in "I Was A Dancer." "I'm a man; an American, a father, a teacher, but most of all, I am a person who knows how the arts can change lives, because they transformed mine. I was a dancer."

In his book, d'Amboise tells of growing up in New York's tough Washington Heights neighborhood in the '40s, and of coming of age in the New York City Ballet under two creative, and sometimes conflicted, titans: George Balanchine, the great Russian-born choreographer, and Lincoln Kirstein, the patron of the arts who is credited with establishing ballet in the United States. We speak with Jacques d’Amboise about his life.

- YouTube: Jacques d'Amboise dances Afternoon of a Faun

- YouTube: Watch d’Amboise dance in the musical “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers" (D'Amboise is in green shirt)

- YouTube: Jacques d'Amboise and Melissa Hayden dance the Nutcracker

- Leave a comment

Book Excerpt: "I Was A Dancer"

By Jacques d'Amboise

Balanchine’s Burial

Balanchine’s Burial

Tuesday, May 3, 1983. Balanchine’s funeral commenced at nine a.m. The church, located on Ninety-third Street between Madison and Park avenues, has a mouthful of a name: Cathedral of Our Lady of the Sign, Synod of Bishops, Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. At Russian Orthodox rites, there are no pews or padded kneeling pillows, so STANDING ROOM ONLY means more than a packed house. By eight a.m., the church was already full, but my family and I squeezed ourselves in, got a candle each, lit them, and by nine o’clock were immovable. A few people fainted standing, unable to fall. Packed together and unaccustomed to standing in place, we undulated in a slow dance, shifting our weight from foot to foot— hot, tense, bereaved, seeking comfort. As I looked up, I’d swear the figures in the icons layered up the walls were rocking too. Hundreds gathered outside the church, blocking the doors.

In the sanctuary, the environment of loss was thick and darker than a shadow’s shadow. On my left, almost crushed by the mass of people, was Tusia, the mouse- like Russian seamstress, four feet tall, weighing about fifty pounds. She had been a devoted serf her whole life to the great costume designer Madame Karinska. As a pagan sorceress or goddess has a familiar to do her bidding (the black cat to a witch, Jiminy Cricket to Pinocchio), so Karinska had her Tusia.

Occasionally, my gaze would meet other pairs of tearful eyes, pause a moment, then sadly move on. Familiar friends nearby received a hug and then a silent separation: Allegra Kent, Merrill Ashley, Kay Mazzo, Tanaquil LeClercq. Across the way stood Alexandra Danilova, the legendary ballerina assoluta (in the ballet world, there is no crown higher). Danilova was known for her gorgeous legs and, at seventy-something years old, she was still teaching. At that time, I was taking her class regularly and admired how beautifully those still-elegant legs demonstrated a battement tendu.

She headed a cluster of balletomanes—a White Russian mafia—seamstresses from Karinska’s costume shop, teachers and administrative staff from the School of American Ballet, and other Russian friends and cronies, all paying homage to the man who epitomized and carried forward pre- Soviet culture through the art of ballet.

Balanchine had preserved vestiges of another time and culture, and to Danilova and all the Russians, he represented St. Petersburg and the Maryinsky Theater before it became Leningrad and the Kirov. As many present-day Cubans loathe Castro, so the White Russians loathed anything Soviet. Balanchine choked with anger when, at the UN in October 1960, Nikita Khrushchev spoke vehemently about how the Communists would someday crush capitalism. Khrushchev took off his shoe and slammed it into the desk before him repeatedly, and said, “We will bury you!” Though you rarely saw Balanchine lose his cool, he was still choking the next day, complaining, “They’re not translating it truthfully! Khrushchev is cursing and using foul language, spewing vulgarities of the most common Russian of the street! Peasant pig talk!”

Over a multitude of heads, I spotted Frances Schreuder, the underwriter of Balanchine’s ballet Davidsbu¨ndlertänze, her back to the wall, her face expressionless. Her son had been convicted of murdering his grandfather, and she was accused of conspiring and instigating the murder. Her trial was scheduled for the fall and she was the only person standing in that church who had space around her.

Eddie Bigelow was at my shoulder. Stuffed into a tall, bony frame with a surly exterior was the heart of a caring, loving man. I reflected—Eddie was there, in thrall to Balanchine and Lincoln, from the earliest days of Ballet Society in 1946. Eddie performed in anything and everything, and was a lifelong servant to dance and dancers. Eddie— filling in for injured corps de ballet dancers; acting the character roles, the monster roles; holding a banner at the back of the stage in Firebird; fixing costumes; running errands; dyeing shoes; carrying injured dancers to the hospital— Eddie could always be counted on. If you needed a moving man, Eddie carried your furniture up and down stairs. A chef? He would cook giant pots of spaghetti, supply the vodka, Chianti, or scotch, and argue with you incoherently for hours, rambling off lots of words that sounded like they meant something, but we never could zero in on what his subject was. We loved to play cards together . . . canasta, poker, bridge. God bless him. In service his whole life! Behindthe scenes Eddie and the self-effacing Betty Cage gave their love, labors, and most of their lives to the ballet company. They should have their Oscars, along with Balanchine and Lincoln.

Suzanne Farrell, white- faced and sheathed in black, stood near the coffin, holding lilies in her arms, like Albrecht in Giselle.

The young, imposing Father Adrian, standing over six feet tall, officiated from the altar. He had been Balanchine’s priest. Russian liturgy echoed off the walls, intoned by Father Adrian and answered by the many Russians in the church. The power of ritual, communally shared, is meant to establish an architecture of order and become a road to healing, yet throughout the ceremony all I registered was the murmuring and the subdued sobs of those around me, as if my brain heard only the bass line of an orchestra. The presence of deep sorrow generates loss, fearfulness, and even anger. The only comfortable person present and at peace was the deceased.

In my unease, my mind wandered and focused on Bigelow, imagining him in the role he created in the ballet La Valse: cloaked in black velvet, white pancake makeup on his face, black circles under his eyes, a shadow of Death; a timeless presence overlooking Balanchine in his coffin.

The high point in the British 1949 movie of Pushkin’s Queen of Spades takes place at the funeral for the old Countess Ranevskaya. The army engineer, Hermann, who brought about her death, leans over the open coffin to kiss her forehead, and her eyes pop open!

Then, I heard it. A little sniff. Didn’t anyone else hear it? It came from Balanchine. One nostril, a slight twitch. Didn’t anyone else see it? I saw it! And then another, and then his mouth twitched. A woman near the coffin began gasping, backing up. Balanchine sitting up! Screams! Bodies paralyzed, frozen with disbelief. Others scrambling to get away. Balanchine was looking around. I pushed my way through the backing multitudes to embrace him. And he announced, “I was sleeping . . .”

The service was reaching its end, and lights faded on the stage. Many of us stayed, lined up to approach Balanchine on his bier. At my turn, I stepped up, touched his hand, petted it, really, tears dripped off my cheek. I leaned over to kiss his forehead. Luckily, I did not drip on his face. What did I expect? Balanchine’s forehead to be cold on my lips! It was warm.

Leaving the church, Shaun told me that Danilova didn’t cry at Balanchine’s funeral because, she claimed, “Makeup and tears don’t mix.”

Carrie, Chris, and I joined Tanny and her buddy, the boyish-looking Randy Bourscheidt, New York City’s deputy commissioner for cultural affairs. We packed ourselves into a limousine, supplied by Nancy Lassalle for Tanny’s use, and followed the cortege, a line of black beetles traveling in limbo-land along the right lane of the Grand Central Parkway. We were being drawn toward Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor, New York, where Balanchine’s plot lay open, calling.

There was no small talk in our vehicle, until . . .

“I don’t believe it!” Randy declared. He was looking out the window. In the left lane, hurtling by, was Frances Schreuder, alone in the back of her limousine and desperately determined. She passed our entourage, the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz melded with Carabosse from Sleeping Beauty.

The cemetery, beautiful with its newborn foliage emerging from winter sleep, was a landscape to rest in. The weather was far from restful, a tumultuous, windswept, gray, watercolored day, but appropriate for the occasion. Lost in grief, we gathered on a knoll a short distance from the roadway. Our small group, less than half a hundred, stood around the coffin— each of us touched in different ways by the monument that Balanchine had been.

A large part of our identities was molded by our association with him. As musical themes introduced in the early movements of a symphony come together in the last movement, so did grief, palpable during the ceremony at the cathedral, unite all of us at the gravesite. Few were without tears. I felt divided— a part of me was separate—watching myself and everyone else in a slow- motion dream. I was playing my part in a silent movie, surrounded by a trio of Balanchine’s ex-wives: Tanny, next to me in her wheelchair; Alexandra Danilova; and Maria Tallchief, a few feet away. The set, a vision of tree branches running their fingers through the wind. Grieving nearby were Karin von Aroldingen; her handsome, salt-and-pepper- haired husband, Morty; and their yellow-haired, teenage daughter, Margot.

Balanchine never had a family of his own in the traditional sense, except the one Karin, Morty, and Margot gave him. They opened up their home to him, and he was Margot’s godfather. He had a comfortable, homey life with them, the kind where you sit around in your underwear reading the morning paper, or watching TV late at night with your feet up on the coffee table and eating junk food. Years earlier, Karin and Morty had acquired a condo for their family in a development in Southampton, and they had persuaded Balanchine to invest in a small one for himself. He loved it there and would cook scrumptious feasts in his sandals and bathrobe. With Karin, Morty, and Margot, he had a life of the ordinary, a world away from Lincoln Center, the State Theater, and his New York City Ballet. The Sag Harbor cemetery is a few miles away from his condo.

We formed a circle, clustered around the grave. Some of us stood alone, others huddled close, perhaps trying to find solace in one

another, but, just as in all death, the solitary is supreme. A quartet of lumpy gravediggers waited on the outskirts, leaning on their shovels, routine for them, since they probably bury half a dozen people a day. Outside our circle, on a solo knoll some twenty- five to thirty yards away, stood Frances Schreuder. Conducting the ceremony, Father Adrian led the prayers, the wind blowing his long, curled hair and belly-warming beard into fluttering black- brown ribbons. After the prayers, one by one we went up to the hole and dropped flowers into it. I pushed Tanny there in her wheelchair, her hands like eagle’s claws gripping the chair’s arms; it seemed all her life forces centered in those clutching fingers. I split the flowers I had, and we threw them on the casket.

The very bones in Tanny’s face seemed to tighten. “Get me out of here,” she said. She was on the verge of screaming, so I quickly wheeled her toward the limousines.

“We’re supposed to go to Gold and Fizdale’s,”* I mumbled, “for the reception.”

“I’m going back to New York,” she screeched. “I’ve got to get out!”

It took a while, returning along the dirt road to where the cars were parked. At Tanny’s limo, she took command, and in clipped, short sentences, ordered a litany of directions: “Don’t forget to lock the wheelchair before you try to lift me out. Now, pick me up carefully. Don’t bang my head against the edge of the door.”

I’d been her partner for years. I used to tell her what to do. I would fling her in the air, catch her, spin her, and always be in total control. At that moment, I was terrified and could barely move.

“Okay, next, make sure my back is placed tight against the seat. Push that switch to fold the chair up, you can put it in the front seat next to the driver. Then you can go, get out!”

Have you ever noticed how quickly mourners leave the cemetery after a burial? Everyone wants to get back to life, as quickly as possible. When I wended my way back to the grave, only the four gravediggers were in sight. As I got closer, I could see someone else, a girl on her knees. It was sweet, round- faced Margot, sprawled out at the edge of the open grave, sobbing, with her arms reaching down toward Balanchine’s casket. The gravediggers stood nearby, uncomfortable, unable to shovel in the dirt.

“Get back, little missy,” one of the shovelers said. “It’s all over.” I put my arms around Margot and lifted her out of the way. Where were Karin and Morty? Tanny had taken the limousine and left. I was at a loss. I didn’t know how to get to the reception. I didn’t know where Carrie and Chris had gone. Frances Schreuder had vanished, and there I was stuck with a dead body and a sobbing teenager.

There was a car coming up the dirt road! Thank God! Karin and Morty were returning with Carrie and Chris to pick us up. PHEW!

When people are under emotional stress, they’re likely to indulge their pleasure centers—go shopping, buy themselves unnecessary gifts, drink, and gorge themselves on food. Or the reverse, they go alone into a dark corner and try to sleep, turn off the world. Everyone was confronting a future without Balanchine. The cemetery crowd gathered at Gold and Fizdale’s to party, and food was being gobbled and wine flowed. I headed straight for the biggest table and proceeded to slurp away, trying to sample every delicacy at the ample smorgasbord. Amidst all these people, grieving the loss of the giant of dance, I reflected that aside from his favorite muse at the moment—and, perhaps, Stravinsky—Balanchine never cared much for anybody.

Someone tugged my sleeve. I looked down, and there was Tusia at my elbow. Woeful Tusia. (The tugging reminded me of her once fiddling with my arm at Madame Karinska’s studio, where I had been summoned for a costume fitting on my day off. It was a sunny, brilliant day, and I stood patiently, half- clad in a pin- studded muslin mock-up of a ballet tunic. Under Madame Karinska’s eye, Tusia basted the gusset, and mumbled, with great foreboding, “Oh, Jacques, you must be careful today. The sun is out.”) Gloom was her nature— she had dark circles under her eyes, even when they weren’t there. Today, at Gold and Fizdale’s, fussing with my sleeve, she mumbled, “Balanchine is gone, Jacques, and soon Madame will be gone. What do we do now? What do we do?” Through a mouthful of shrimp remoulade, I managed, “What do you mean, what do we do? We do what we always do. We eat and

drink and keep going.”

Tanny had bolted with the limousine, so, champagne glass in hand, I made the rounds, trying to solicit a ride home. “L’chaim!” I proclaimed with every glass. A Hebrew toast, from a people who have suffered great loss and tragedy— responding with a cry “TO LIFE!” Go on, survive, continue! We had him once a little while, and dance did sport with song, but now no more.

I was reminded of a line from Aeschylus’ The Persians: “Death is long and without music.”

In August 2003, Karin von Aroldingen and I visited Balanchine’s grave. Standing on the grass over him, I took Karin in my arms, and we danced a waltz. There was an audience. Across a dirt path, less than ten yards away, stood a single headstone bearing the names of Gold and Fizdale; they were buried beneath, one on top of the other. Around a corner of the path was Alexandra Danilova’s grave.

Right around the death of Balanchine, I flippantly mentioned to a friend, Hope Cooke, “After fifty, it’s harder to stay in the air.”

But National Dance Institute kept my fingerprints on the ceiling, and has allowed me to spend a life playing my games— not so different from the stoop in Washington Heights (“You’re going to be pirates!” I’d order my pals from the gang. “I’ll be the captain! Here are your swords.”) Though at the start, I wanted only to introduce children (boys especially) to the magic of dance and the arts, NDI became my way of interpreting Balanchine and Lincoln’s legacy— bringing together the highest caliber of artists from the worlds of music, dance, and the visual arts, in collaborations on the highest level— only applying and evolving this legacy in service to children, and vice versa (children in service to the arts).

Copyright © 2011 by Jacques d'Amboise

This segment aired on March 2, 2011.