Advertisement

Black Pilgrim Stirs Controversy, 30 Years On

Resume

by Kevin Sullivan

Was there a black pilgrim breaking bread with the Puritans in the 1620s?

That question caused a huge controversy in the 1980s when the Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Mass. hired a black actor to portray a pilgrim.

The Plantation reproduces the pilgrims’ 17th century village, complete with period buildings, food and role-playing interpreters, who speak as though it were 1627.

In 1981, Bob Marten was the museum’s director of programs. He said that the museum had begun receiving federal funds, and that required them to advertise as an equal opportunity employer.

An African American applied for a role playing job, and Marten hired him. He said there had been black people in Plymouth at the time of the pilgrims, so it seemed logical.

But some historians and descendants of pilgrims balked, and the museum decided if there was going to be a black pilgrim at the museum, he had to be based on a real person.

Marten said that for more than 100 years, historians had referenced a black pilgrim, named Abraham Pearse, who came to Plymouth in 1623.

The Blackamore

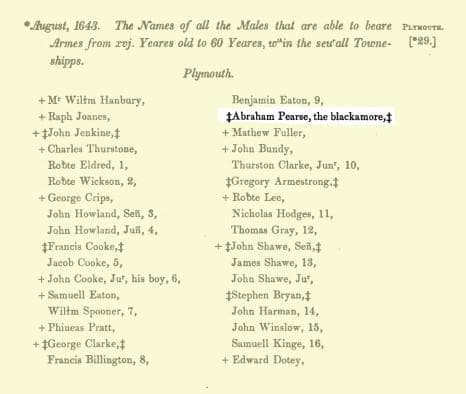

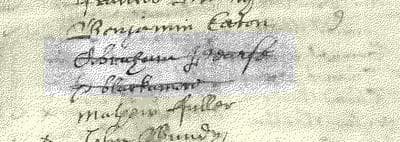

Marten did some research and found an entry in the 1861 publication, “Records of the Colony of New Plymouth in New England 1633 – 1689” that read:

"Abraham Pearse, the blackamore."

Blackamore was a term for a black person in those days.

“A number of historians with experience examining the records have looked at it over the years, and without exception that we know of, they would concur that he was a black man,” Marten said.

But Marten said some descendants of Abraham Pearse did not concur.

Marten said, “One of these descendants said to me, ‘You took all the fun out of being a pilgrim descendant. It was a thing of great pride to be related to this nobility and if these pilgrims, if some of them were black men, then that prestige, all the fun of being a descendant of a pilgrim is gone.’”

Additional Research

The museum decided additional information was needed, and they brought in other museum researchers, including Jim Baker, to investigate.

Marten had based his case on the 1861 publication. But it turns out that book was a transcription of a slew of colonial records. Baker found the original 1643 document, and found that it read differently. On one line was the name, Abraham Pearse, and under his name (not next to it), read the words: the blackamore.

Baker interpreted that to mean, there were actually two men, Abraham Pearse, and an unidentified black man.

“Pearse appears in the colonial record at least 30 times,” Baker said. “He marries someone who is obviously part of the regular community. His children continue on and have descendants. There's never any mention that he was noticeably black.”

Bob Marten disagrees. He says that the single reference to Pearse’s race is consistent with other colonial records. And he notes that other people through history, including the 19th century abolitionist, Charles Sumner, also referred to Pearse as a black pilgrim.

The DNA Trail

Fast-forward to the 21st century. We now live in the age of CSI, where sophisticated DNA tests could put this controversy to rest.

In fact, amateur genealogist and radiologist Dr. Brad Pierce of Little Rock, Ark., has reviewed DNA tests of two Abraham Pearse descendants.

“We can say with virtual certainty that the father of Abraham and his ancestors on the male Pearse line are not of African descent,” Dr. Pierce said. “The DNA suggests that it has a characteristic that suggests they are of Scandinavian descent.”

But Abraham Pearse could have African ancestry on his mother’s side.

Dr. Pierce explained that he traced the Pearse descendants to Abraham Pearse through their Y chromosome, which is passed down from father to son. In order to determine Abraham Pearse’s mother, you would have to trace his X chromosome, which fathers pass down to female offspring, and mothers pass down to both males and females. As far as we know, no one has done that research.

Another Black Pilgrim

It turns out that there was another black man, named John or Juan Pedro, who did live in Plymouth from 1623 to 1624. So why can’t the Plimoth Plantation base a black pilgrim character on him?

Jim Baker said the museum is based on a specific year, 1627, and Pedro left Plymouth in 1624.

“We're looking at a specific year with a specific list of people, which we happen to have by name there in this particular year,” Baker said. “And sliding someone in before or after, simply negates what the plantation is up to and trying to represent.”

Bob Marten ended up losing his job for speaking to the press about the whole controversy. He said he was authorized to speak, the museum said he was not.

Marten still lives in Plymouth, and hopes that one day, Abraham Pearse will be recognized as the first black pilgrim.

“I'd like to see black, historically-oriented people, who work in the field of black history [conduct] research on Abraham Pearse and the pilgrims, and become an authority on the subject,” Marten said.

As of today, there is no black pilgrim at the Plimoth Plantation, but museum officials say they hope to one day expand, and build a farm-tavern that could include characters from 1620 through 1689, which would allow for someone to portray at least John Pedro as a black pilgrim.

This segment aired on November 24, 2011.