Advertisement

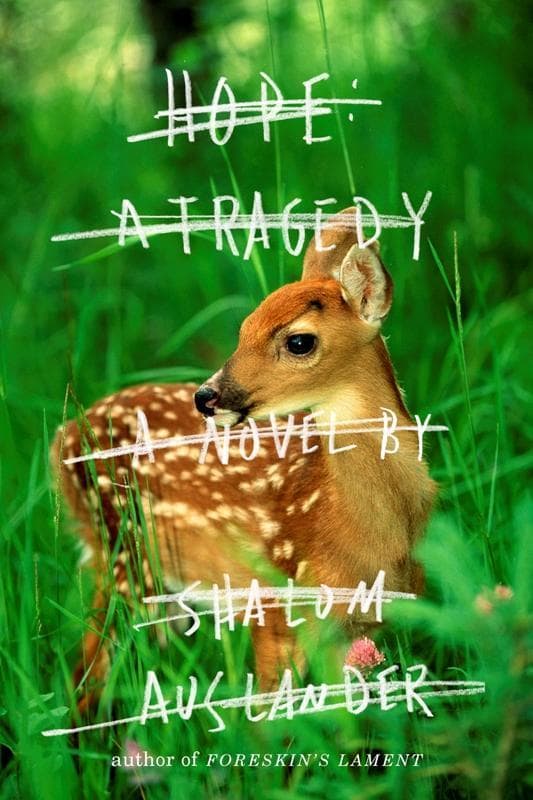

Shalom Auslander Weaves Anne Frank And The Holocaust Into Dark New Novel

Resume

Shalom Auslander won acclaim for his short stories and his 2007 memoir "Foreskin's Lament," which took a scathing, but funny look at his Orthodox Jewish upbringing.

In "Hope: A Tragedy," the main character Solomon Kugel has moved with his family to a house in rural upstate New York to get away from it all.

Their peace and quiet are disrupted first when his mother moves in. She was born and raised in privilege in New York and she has delusions of being a Holocaust survivor.

Their lives are then completely thrown up in the air when Solomon discovers an old woman living in the attic who turns out to be Anne Frank.

She's not only alive, but profane, demanding, and working on a follow up to her world-famous diary.

Auslander says that while his memoir looked at "how to live in a world with a crazy, brutal God," his new book is about "how to live on a planet with crazy, brutal, human beings."

Book Excerpt: Hope A Tragedy

By Shalom Auslander

Chapter 1

It’s funny: it isn’t the fire that kills you, it’s the smoke.

It’s funny: it isn’t the fire that kills you, it’s the smoke.There you are, pounding on the windows, climbing higher and higher through your burning home, trying to get away, to get out, hoping that if you can just avoid the flames, perhaps you’ll survive the fire, but all the time you’re suffocating slowly, your lungs filling with smoke. There you are, waiting for the horrors to come from some there, from some other, from without, and all the while you’re dying, bit by airless bit, from within.

You buy a handgun—for protection, you say—and drop dead that night from a heart attack.

You put locks on your doors. You put bars on your windows. You put gates around your house. The doctor phones: It’s cancer, he says.

Swimming frantically up to the surface to escape from a menacing shark, you get the bends and drown.

You resolve, one sunny New Year’s Day, to get back into shape. This is the year, you insist. A new beginning. A new start. A stronger you, a tougher you. At the health club the following morning, just as you’re beginning your third set of bench presses, your muscles cramp and the barbell collapses onto your neck, crushing your windpipe. You can’t cry out. Your face turns blue. Your arms go limp. There, on a poster on the wall beside you, are the last words you see before your eyes close and darkness envelopes you for eternity:

Feel the Burn.

It’s funny.

Chapter 2

Solomon Kugel was lying in bed, thinking about suffocating to death in a house fire, because he was an optimist. This was according to his trusted guide and adviser, Professor Jove. So desperate was Kugel for things to turn out for the best, proclaimed Professor Jove, that he couldn’t stop worrying about the worst. Hope, said Professor Jove, was Solomon Kugel’s greatest failing.

Kugel was trying to change. It wouldn’t be easy. He hoped that he could.

Kugel stared silently at the ceiling above his bed and listened.

He heard something.

He was certain of it.

Up there.

In the attic.

What is that? he wondered.

A scratching?

A rapping?

A tap-tap-tapping.

The other reason Solomon Kugel was lying in bed, thinking about suffocating to death in a house fire, was that someone was burning down farmhouses, just like the one he and his wife had recently purchased. The arson began soon after the Kugels moved in; three farmhouses had been torched in the six weeks since. The Stockton chief of police vowed he would catch whoever was responsible. Kugel was hopeful that he would, but hadn’t slept since the first farmhouse lit up and burned down.

There it was again.

That sound.

Maybe it was mice.

It was probably mice.

There are a hundred farms around here, jackass. Why would he target you? It’s farm country.

You’re frightening yourself.

You’re torturing yourself.

It’s narcissistic.

It’s delusions of grandeur.

It’s optimism.

It’s mice.

Didn’t sound like mice, though.

Kugel thought frequently about death and even more frequently about dying. Was this, too, he wondered, because he was an optimist? Precisely, Professor Jove had declared. Kugel loved life, observed Professor Jove, and so he expected far too much of it; hell-bent on life, he was terrified that someone would cause, by violence or accident, his untimely death. Kugel, in his own defense, pointed out that he didn’t think anyone was actually trying to kill him, he simply thought it well within the realm of possibility that somebody, unbeknownst to him and for reasons yet to be revealed, might be; there is a line, he argued, thin as it may be, between paranoia and pragmatism.

Kugel’s mother, for her part, worried less about death than she did about life. Her own life, sadly, had gone too well, too smoothly; above average in comfort and security, below average in suffering and pain; better than anyone had a right to expect and callously lasting far longer than anyone could rightly demand. Alive, and happy, she cried.

Kugel thought specifically about the experience of dying. He thought about the pain, about the fear. Most of all, he thought about what he would say at the final moment; his ultima verba; his last words. They should be wise, he decided, which is not to say morose or obtuse; simply that they should mean something, amount to something. They should reveal, illuminate. He didn’t want to be caught by surprise, speechless, gasping, not knowing at the very last moment what to say.

No, wait, I oof.

I haven’t really given it much splat.

If I could just ka-blammo.

We are all mankind a story, collectively and individually, and Kugel didn’t want his individual story to end in an ellipsis. A period, sure, if you’re lucky. An exclamation mark, okay. A question mark, probably; that seemed the punctuation all stories, collectively and individually, should end with after all.

Not an ellipsis, though.

Anything but an ellipsis.

Don’t end it like this, said Pancho Villa, at a loss for words after being shot nine times in the chest and head. Tell them, he said before dying, I said something.

Kugel kept a small notebook and pen with him at all times for just these thoughts; now and then, when a fitting last sentiment or final set of words occurred to him, he would quickly write them down. Over the years he had filled many such notebooks but had yet to arrive at the precise right notion. The difference between the right word and the wrong word, said Mark Twain, is the difference between lightning and the lightning bug.

Twain’s last words, to his daughter, were: If we meet . . .

Then he died.

So timing’s important, too.

Kugel hoped, when the time came, that whatever he said would someday be re-said; would be heard and retold, for however many generations remained before The End. He hoped it would be something his beloved son, Jonah, could remember; something the boy could look to in times of trouble long after his father had passed, and find within those few carefully chosen words some light, some guidance, some wisdom (assuming, of course, that Jonah didn’t predecease him, or that they didn’t die together, father and son, in some tragic accident; were that to be the case, Kugel knew exactly what he would say to Jonah as the plane, for example, was plunging toward earth: he would say, I’m sorry. I’m sorry, but at least it’s over. Or something to that effect: Well, son, that was the rough part. The living’s over. After this, kid, it’s all gravy . . . ).

This, ultimately, is what Kugel hoped: that his last words would somehow make all this amount to something, all this . . . this life, this effort, this toil and time and terror. This unintentioned, unrelenting existence. That it wasn’t just a stage, that we weren’t merely players. Kugel could never believe in God, but he could never not believe in him, either; there should be a God, felt Kugel, even if there probably wasn’t.

According to Luke, author of the Gospel of the same name, Jesus, dying on the cross, said this: Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.

Eh.

A little obvious. A little self-congratulatory. A little smug. Where else was your spirit going to go but to God? The moment before you meet your Maker is probably not the best time to be acting like you’re doing Him some big favor by commending Him your soul.

Kugel was approaching forty, and though he hadn’t yet decided for certain what he wanted his last words to be, he had long known for certain what he didn’t want them to be: he didn’t want them to be begging. More than anything, he didn’t want to beg. No pleases. Or nos. Or waits. Or please, nos; or no, waits; or wait, pleases. Or no, no, nos. Or please, please, pleases. Or wait, wait, waits.

Please don’t hurt me, Louis XV’s mistress begged her executioner as he led her to the guillotine.

He hurt her.

Let’s cool it, brothers, said Malcolm X to his assassins.

They shot him sixteen times.

Perhaps they had cooled it, thought Kugel. Perhaps they’d been planning on shooting him twenty times. It behooves the victim, in these matters, to be specific.

Kugel’s dread of begging was due to neither a sense of pride nor a surfeit of courage; he simply hoped that he wouldn’t be in a situation where begging might help. You can’t beg old age. You can’t beg cancer. He could live with those deaths. You can’t beg a car not to hit you, a piano not to fall on your head. You can only beg people. Any situation where begging might be of some assistance had to be one in which your life was in the hands of another human being, a woefully precarious place for your life to be in. Kugel was determined not to die at the hands of another, if only to disprove his mother, who insisted that her last words, and her son’s last words, and her son’s son’s last words, whatever they might be, would be said in a gas chamber.

Or in an oven.

Or at the bottom of a mass grave.

Or at the top of a mass grave.

There it was again. That tapping sound.

Placement in the mass grave mattered, Kugel supposed, only if you were still alive; if they shot you somehow in the leg or arm, and your wounds weren’t fatal. In that case, it would be a far, far better thing to be at the bottom of the mass grave, where the weight of the corpses piled above would crush you to death and end your life quickly, mercifully, rather than dying slowly and painfully at the top of the corpse pile, perhaps even being alive when they buried you.

Tap. Tap-tap-tap.

He was sure of it.

In the attic.

Unless they shot into the corpse pile a second time. Then, of course, top of the corpse pile might be better.

This is what Samuel Beckett’s father said right before he died: What a morning.

A bit of irony, thought Kugel. A smile. The laugh that laughs at that which is unhappy.

Or dropping dead.

He might use that:

What a day.

Looks like rain, suckers.

Kugel wondered what his own father’s last words were, or if he had last words, or if he was dead or if he was alive.

Mistakes were made?

Kugel had a theory. Kugel was certain that whatever last words a person chose to utter in his final moments, everyone shared the same final thought, and this was it: the bewildered, dumbfounded statement of his own disappointing cause of death.

Shark?

Train? Really? I get hit by a train?

Malaria? Fuck off. Malaria?

Regardless of what was spoken, this and only this was a human’s last thought, the last pure cognition that passed through a human being’s mind, every human being’s mind, before that mind ceased to function evermore. Not Shema yisroel adonai elohainu adonai echad. Not Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned. Only the ludicrous, laughable cause of its own unfathomable demise.

Cancer?

Tuberculosis?

Benito Mussolini’s last words, as he faced his executioner were these:

Shoot me in the chest!

His last thought, though, Kugel was certain, was this:

Shot in the chest?

There it was again—that sound.

A scurrying of sorts. A sliding.

Kugel sat up.

It was something.

There was something up there.

No death, after all, does any life any justice. Our endings are always a letdown, an insult, a surprise, dumber than we thought and less than we’d hoped for.

Crucifixion? thought Jesus. Get out.

Hemlock? thought Socrates.

Wrapped in a Torah scroll and burned alive? thought Rabbi Akiva. You have got to be shitting me.

That sound again.

What did an arsonist sound like, anyway?

Kugel listened.

Beside him, he could hear his Brianna, his Bree, his hero, his love, deep in her wonderful Prozacian slumber. He could hear Jonah, across the hall, bedsprings creaking as he shifted in his own deep sleep. Tylenolian.

It’s a tough place to get some sleep.

Earth, that is.

Of course they didn’t always shoot a second time into the mass graves.

That’s life for you: a colossal inescapable corpse pile—and no second shooting.

Kugel crept quietly from the bed and knelt on the floor beside the heating vent at the side of his nightstand. The wooden floor was hard against his knees, but he put his hands on either side of the vent, bent over, and pressed his ear against the cold metal register.

Through the vent, he could hear the tenant moving about in his bedroom downstairs (he’d moved in two weeks before, and Kugel still couldn’t recall his name; it was Isaac, or Ishmael, or Esau—something biblical); he could hear the buzz of applause and laughter coming from the tenant’s TV, which the tenant left on all night long. Below that he could hear Mother, in her bedroom beside the tenant’s, moaning in agony and pain. Mother was alive if she sounded like she was dying; if she sounded like she was peacefully sleeping, then she was probably dead.

And he could definitely hear tapping.

Upstairs.

In the attic.

A ticking?

A tapping.

As if some mouse were gently crapping, crapping on his attic floor.

Like little mouse feet.

Like typing, almost.

Marsupial Proust, he joked. Jules Vermin. Franz Krapper.

It was probably just mice.

Quietly, so as not to wake Bree, Kugel stood, pulled on his robe, took the tall metal flashlight from beside his bed, tiptoed as best he could across the old, creaky floorboards, and stepped out into the coolness of the dark hallway.

Would an arsonist start a fire in the attic?

Don’t they start them outside? Around the foundation?

It’s not an arsonist.

You’re being ridiculous.

He grabbed the rope that hung from the attic door, and pulled it slowly toward him, hoping not to find an arsonist, hoping to find a mouse, hoping, at the very least, to find some mouse droppings; if he found mouse droppings he would know it had been a mouse making the noise, and then perhaps he could at last get some sleep.

Such is life, he thought as he unfolded the wooden attic stairs: you get to a point, one day, where you are hoping to find crap; where the best possible outcome of all possible outcomes would be the discovery, praise Jesus, of a pile of shit.

Kugel climbed the creaky stairs as quietly as he could.

Maybe it was a mouse.

He reached the top of the stairs. The attic felt hot, hotter than the rest of the house. The tapping suddenly ceased.

Hello? whispered Kugel.

Probably just a mouse.

Hello?

And, hearing no reply, Kugel crawled into the dank, damnable darkness above.

Excerpted from HOPE: A TRAGEDY by Shalom Auslander by arrangement with Riverhead Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc., Copyright © 2011 by Shalom Auslander.

This segment aired on January 19, 2012.