Advertisement

Getting To Know Romney

Resume

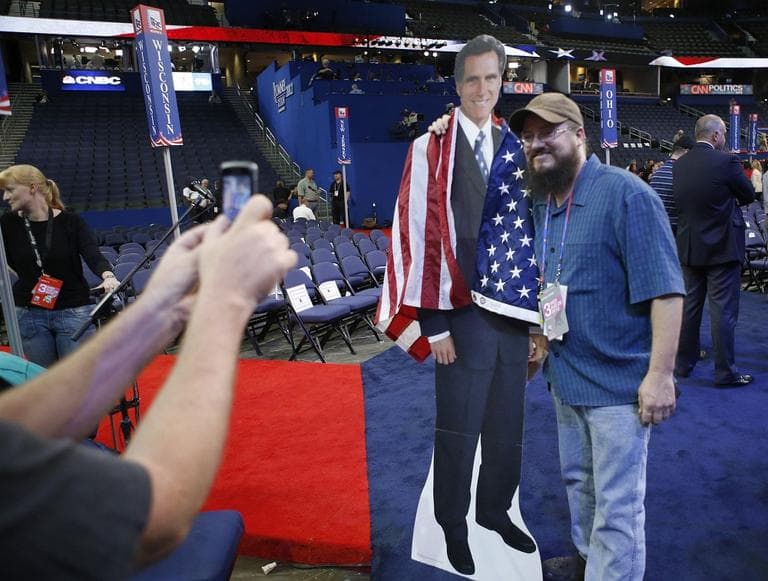

A third of Americans say they don't know Mitt Romney well enough to have an opinion about him according to the latest CBS poll. And in another poll, only 27 percent say they like him.

Thursday night is Romney's big chance to change all that. He'll address the Republican Party and the nation for the first time as a Presidential nominee. Reporters Michael Kranish and Scott Helman say to understand tonight, look back to the 1964 Republican Convention.

Moderate Republican leader George Romney asks his Party to reject extremists in 1964. The GOP instead went on to nominate Barry Goldwater, whose acceptance speech included the words, "extremism in defense of Liberty is no vice; Moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue."

How will that Convention shape Mitt Romney's speech on Thursday?

- Here & Now: Bain Capital Grapples With Increased Scrutiny

Book Excerpt: "The Real Mitt Romney"

by Michael Kranish and Scott Helman

PROLOGUE

When he finally enters the auditorium, they jump to their feet, the murmur crescendoing to a spirited ovation. Through a gauntlet of whoops, whistles, fist pumps, and camera flashes, he emerges, microphone in hand, his charcoal hair speckled with gray, wearing an easy smile as the warm reception washes over him. “Let’s go, Mitt!” someone screams. He mildly protests the adulation, imploring everyone to sit down, to please sit down. On this balmy autumn day in New Hampshire, in a campaign being fought very much on his turf, Willard Mitt Romney is confident, serenely so. He’s an old hand at this now. He’s ditched the stiff suits for cuffed khakis, scrapped the elaborate stagecraft for a minimalist presentation— just a guy holding court at a modest town hall meeting, ready for anything from voters who feel entitled to this ritual of political intimacy. He opens with a patriotic riff, promising “a campaign of American greatness.” He wants everyone to know: Mitt Romney loves America, and he believes in its people.

It is a simple, Reaganesque anthem, served up to a Republican audience hungry for a credible, electable leader who will deny President Barack Obama a second term. Romney’s whole demeanor, here at the center of this theater- in- the- round at Saint Anselm College in Manchester, New Hampshire, is meant to convey, beyond any doubt, that he is ready. If he could take over now, he would. Just give him the keys to the White House. Why wait? After all, he’s been preparing for this moment— his moment— all his life. Many politicians say that. Or have it said about them. In Mitt Romney’s case, to a remarkable degree, it happens to be true.

He is, as he likes to say in debates, in speeches, and on the stump, a turnaround specialist running to lead a nation that desperately needs one. In his narrative, President Barack Obama has steered the country into a ditch, and Mitt Romney is the only one capable of yanking it out. Mr. Fix- it, reporting for duty. He’s already fixed his approach as a candidate, self- assured and savvy where he was often slipshod and self- defeating in 2008. He is, as one local politician tells him pointblank at Saint Anselm, a far stronger contender than he was four years ago, much more at home in a campaign centered on the economy. Last time, Romney looked like an actor playing a presidential candidate. This time, he seems like the real thing.

All around him on this day, mounted high on the walls of the college’s New Hampshire Institute of Politics, are imposing photos of men who have achieved what he has long dreamed about. There’s George H. W. Bush in a red jacket, standing with supporters near the ocean in Maine. There’s Bill Clinton on the tarmac beside Air Force One. There’s Jimmy Carter with Bill and Jeanne Shaheen, one of New Hampshire’s most famous political couples. But on these walls also hang reminders of the brutal selectivity of presidential politics, of the men whose reach came up short. There’s Bill Bradley shooting a basketball in a tweed coat and red tie. There’s the young Al Gore, in blue jeans and a barn jacket, on the doorstep of a man who is evidently not thrilled at the visit. And then, down a hallway in a quiet corner, is an even more poignant reminder that politics is a fickle business.

There, at eye level, in a simple black frame against a wood panel, hangs a campaign poster from the 1968 presidential bid of his father, George Romney, a Republican moderate who bowed out of the race Richard Nixon would go on to win. The poster, in keeping with the era, has a psychedelic feel, with the words i want romney in ’68 printed in a fun- house font that wouldn’t be out of place on a Jimi Hendrix concert flyer. George is smiling broadly in the gray- and- white rendering of his handsome face, his teeth impossibly white and his hair helmetlike in its perfection. It is an image strangely in tune with the moment, an artifact of both inspiration and warning.

This book is the first complete, independent biography of Mitt Romney, a man whose journey to national political fame is at once remarkable and thoroughly unsurprising. It would have been unthinkable to his ancestors just a few generations ago, yet countless people whose lives intersected with Romney’s over the past seven decades have drawn the same conclusion: this man might just be president someday. The Real Romney, which draws on our many years tracking the man and his career for The Boston Globe, is an attempt to capture him in whole, to plumb the many chapters of his life for insight into his character, his worldview, his drive, and his contradictions.

It is the story of a man guided by his faith and firmly grounded in family. It is the story of a once marginal and feared religion, Mormonism, a brand of Christianity homemade in America that he and his forebears helped move to the mainstream. It is the story of the counterculture movement of the 1960s and the proudly square young man who found it all appalling. It is the story of the wildly lucrative world of private equity and leveraged buyouts, a world largely opaque to outsiders, in which wealth is built and concentrated in novel ways, sometimes at others’ expense. It is the story of an uneasy relationship between conviction and vaulting ambition and how political dreams can die when tactics outrun beliefs. And it is the story, of course, of a father and a son, George and Mitt Romney, and the ways in which their lives aligned and diverged.

George Romney remains, more than four decades after his own adventure in presidential politics and sixteen years after his death, a constant spiritual presence at his son’s side. When a young girl asks Mitt Romney during the New Hampshire gathering what he would tell her class to make them want to be politicians, he deadpans at first, saying “The answer is: nothing. Don’t do it. Run as far as you can.” But when he turns serious, he invokes the advice he says his father offered years ago: “He said, ‘Don’t get into politics as your profession. . . . Get into the world of the real economy. And if someday you’re able to make a contribution, do it.’ ” This is the essence of Romney’s pitch, and it has been ever since his days as a deal maker in the 1980s and 1990s. He’s made his money— a mountain of it, in fact— and believes, as his father did, that he now owes a debt to the country that made a place for him.

From THE REAL ROMNEY by Michael Kranish and Scott Helman Copyright © 2012 by Michael Kranish and Scott Helman. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Guest:

- Michael Kranish, Boston Globe reporter

- Scott Helman, Boston Globe reporter

This segment aired on August 30, 2012.