Advertisement

Top Neurosurgeon Claims 'Proof Of Heaven'

Resume

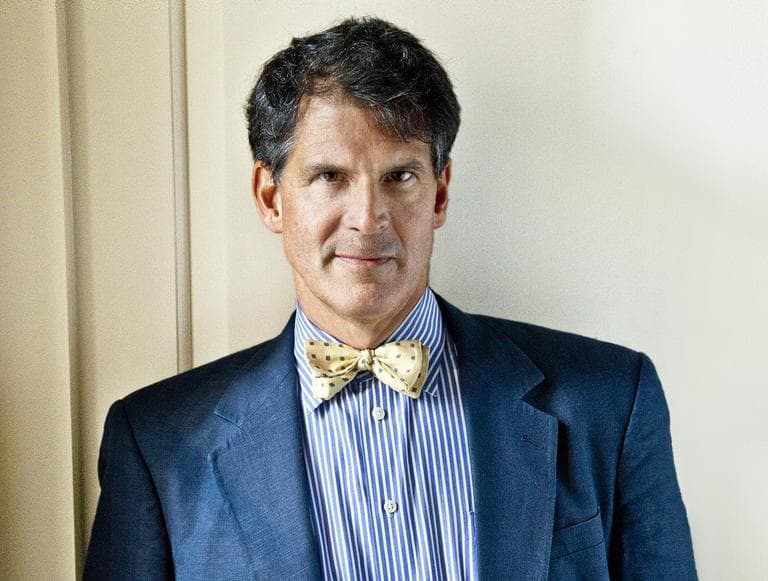

Dr. Eben Alexander is prompting much discussion over his claim that near-death experiences are real, and that human consciousness exists outside of the body.

In his best-selling memoir, "Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon's Journey into the Afterlife," he wrote about a near-death experience he had a few years back after contracting a rare form of bacterial meningitis that left him in a week-long coma.

Even though medically his brain wasn't capable of generating thoughts, he claimed that while in his coma he met a guardian angel and traveled through many realms of existence to meet a divine being he calls Om.

Prominent atheist and author Sam Harris has disputed Dr. Alexander's reasoning, saying the experience does not prove there is an afterlife.

Harris wrote in his blog, "Alexander’s account is so bad—his reasoning so lazy and tendentious—that it would be beneath notice if not for the fact that it currently disgraces the cover of a major newsmagazine."

- New York Times: Readers Join Doctor’s Journey to the Afterworld’s Gates

- Newsweek: The Science of Heaven

- Newsweek: Heaven Is Real: A Doctor’s Experience With the Afterlife

Do you believe in an afterlife? Let us know on our Facebook page.

____Book Excerpt: 'Proof of Heaven'

By: Eben Alexander, M.D.____

A man should look for what is, and not for what he thinks should be.

— Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

When I was a kid, I would often dream of flying.

Most of the time I’d be standing out in my yard at night, looking up at the stars, when out of the blue I’d start floating upward. The first few inches happened automatically. But soon I’d notice that the higher I got, the more my progress depended on me – on what I did. If I got too excited, too swept away by the experience, I would plummet back to the ground… hard. But if I played it cool, took it all in stride, then off I would go, faster and faster, up into the starry sky.

Maybe those dreams were part of the reason why, as I got older, I fell in love with airplanes and rockets – with anything that might get me back up there in the world above this one. When our family flew, my face was pressed flat to the window from takeoff to landing. In the summer of 1968 when I was fourteen, I spent all the money I’d earned mowing lawns on a set of sailplane lessons with a guy named Gus Street at Strawberry Hill, a little grass strip “airport” just west of Winston-Salem, the town where I grew up. I still remember the feeling of my heart pounding as I pulled the big cherry red knob that unhooked the rope connecting me to the tow-plane and banked my sailplane toward the field. It was the first time I had ever felt truly alone and free. Most of my friends got that feeling in cars, but for my money being a thousand feet up in a sailplane beat that thrill a thousand times over.

In college in the 1970’s I joined the University of North Carolina Sport Parachuting (or Skydiving) Team. It felt like a secret brotherhood – a group of people who knew about something special and magical. My first jump was terrifying, and the second even more so. But by my twelfth jump, when I stepped out the door and had to fall for more than a thousand feet before opening my parachute (my first “10 second delay”), I knew I was home. I made 365 parachute jumps in college and logged over three and a half hours in freefall, mainly in formations with up to 25 fellow jumpers. Although I stopped jumping in 1976, I continued to enjoy vivid dreams about skydiving, which were always pleasant.

The best jumps were often late in the afternoon, when the sun was starting to sink beneath the horizon. It’s hard to describe the feeling I would get on those jumps: a feeling of getting close to something that I could never quite name but that I knew I had to have more of. It wasn’t solitude exactly, because the way we dived there actually wasn’t all that much of that. We’d jump five, six, sometimes ten or twelve people at a time, building freefall formations. The bigger and the more challenging, the better.

One beautiful autumn Saturday in 1975, the rest of the UNC jumpers and I teamed up with some of our friends at a paracenter in eastern North Carolina for some really great formations. On our penultimate jump of the day, out of a D18 Beechcraft at 10,500 feet, we made a ten-man snowflake. We managed to get ourselves into complete formation before we hit the 7,000 foot mark and thus were able to enjoy a full eighteen seconds of flying the formation down a clear chasm between two towering cumulus clouds before breaking apart at 3,500 feet and tracking away from each other to open our chutes.

By the time we hit the ground the sun was down. But by hustling into another plane and taking off again quickly, we managed to get back up into the last of the sun’s rays and do a second sunset jump. For this one, two junior members were going to get their first shot at flying into formation – that is, joining it from the outside rather than being the base or pin man (which is easier because your job is essentially to fall straight down while everyone else maneuvers toward you). It was exciting for the two junior members, but also for us more seasoned ones because we were building the team, adding more experienced jumpers who would be able to join us for even bigger formations.

I was to be the last man out of the Cessna-195 in a six-man star attempt above the runways of the small airport outside the bustling town of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina. The guy right in front of me, from the Roanoke Rapids team, was named Chuck. Chuck was also fairly experienced at “Relative Work” – that is, building freefall formations. We were still in sunshine at 7,500 feet, but two and a half miles below us the streetlights were blinking on. Twilight jumps were always sublime and this was clearly going to be a beautiful one.

Even though I’d be exiting the plane a mere second or so behind Chuck, I’d have to move fast to catch up with everyone. I’d rocket straight down headfirst for the first seven seconds or so. This would make me drop almost 100 MPH faster than my friends so that I could be right there with them after they had built the initial formation.

Normal procedure for RW jumps was for all jumpers to break apart at 3,500 feet and track away from the formation for maximum separation. Each would then “wave –off” with his arms (signaling imminent deployment of his parachute), turn to look above to make sure no others were above him, then pull the ripcord.

“Three, two, one...Go!”

The first four jumpers exited, then Chuck and I followed close behind. Upside down in a full head dive and approaching terminal velocity, I smiled as I saw the sun setting for the second time that day. After streaking down to the others, my plan was to slam on the air brakes by throwing out my arms (we had fabric wings from wrists to hips that gave tremendous resistance when fully inflated at high speed) and aiming my sleeves and pants legs straight at the oncoming air.

But I never had the chance.

Plummeting toward the formation, I saw that one of the new guys had come in too fast. Maybe falling rapidly between nearby clouds had him a little spooked – it reminded him that he was moving about 200 feet per second towards that giant planet below, partially shrouded in the gathering darkness. Rather than slowly joining the edge of the formation, he’d barreled in and knocked everybody loose. Now all five other jumpers were tumbling out of control.

They were also much too close together. A skydiver leaves a super-turbulent stream of low-pressure air behind him. If a jumper gets into that trail, he instantly speeds up and can crash into the person below him. That, in turn, can make both jumpers speed up and crash into anyone who might be below them. In short, it’s a recipe for disaster.

I angled my body and tracked away from the group in order to keep from adding to the tumbling mess. I maneuvered until I was falling right over “the spot,” a magical point on the ground above which we were to open our parachutes for the leisurely two minute descent down to the target on the drop zone.

I looked over and was relieved to see that the disoriented jumpers were now also tracking away from each other, dispersing the deadly clump.

Chuck was there among them. To my surprise, he was coming straight in my direction. He stopped directly beneath me. With all of the group’s tumbling, we were passing through 2,000 feet more quickly than Chuck had anticipated. Maybe he thought he was lucky and didn’t have to follow the rules – exactly. He must not see me. The thought barely had time to go through my head before Chuck’s colorful pilot chute blossomed out of his backpack. His pilot chute caught the 120-mph breeze coming around him and shot straight towards me, pulling his main parachute in its sleeve right behind it.

From the instant I saw Chuck’s pilot chute emerge, I had a fraction of a second to react. For it would take less than a second to tumble through his deploying main parachute, and – quite likely – right into Chuck himself. At that speed, if I hit his arm or his leg I would take it right off, dealing myself a fatal blow in the process. If I hit him directly, both our bodies would essentially explode.

People say things slow down in situations like this, and they’re right. My mind watched the action in the microseconds that followed as if it were watching a movie in slow motion.

The instant I saw the pilot chute, my arms flew to my sides and I straightened my body into a head dive, bending ever so slightly at the hips. The verticality gave me increased speed, and the bend allowed my body to add first a little, then a blast of horizontal motion as my body became an efficient wing, sending me zipping past Chuck just in front of his colorful blossoming Paracommander parachute.

As I passed him I was moving at over 150 MPH, or 220 feet every second. Given that speed I doubt he saw the expression on my face. But if he had, he would have seen a look of sheer astonishment. Somehow I had reacted in microseconds to a situation that, had I actually had time to think about it, would have been much too complex for me to deal with.

And yet... I had dealt with it. It was as if, presented with a situation that required more than its usual ability to respond, my brain had become, for a moment, super-powered.

How had I done it? Over the course of my twenty-plus year career in academic neurosurgery – of studying the brain, observing how it works, and operating on it – I had plenty of opportunities to ponder the question. I finally chalked it up to the fact that the brain is simply a truly extraordinary device: more extraordinary than we can even guess.

I now realize that the real answer to that question is much more profound. But I had to go through a complete metamorphosis of my life and worldview to glimpse that answer. This book is about the events that changed my mind on the matter. They convinced me that, marvelous a mechanism as the brain is, it was not my brain that saved my life that day at all. What sprang into action the second Chuck’s chute started to open was another, much deeper part of me. A part that could move so fast because it was not stuck in time at all, the way the brain and body are.

This was the same part of me, in fact, that had made me so homesick for the skies as a kid. It’s not only the smartest part of us, but the deepest part as well, yet for most of my adult life I was unable to believe in it.

But I do believe now, and the pages that follow will tell you why.

Excerpted from the book PROOF OF HEAVEN by Eben Alexander, M.D. Copyright © 2012 by Eben Alexander. Reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster.

Guest:

- Dr. Eben Alexander, author of "Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon's Journey into the Afterlife." He also runs a science and spirituality nonprofit called Eternea.

This segment aired on November 27, 2012.