Advertisement

The Enduring Appeal Of 'Hallelujah'

Resume

Since Leonard Cohen recorded his now-famous song "Hallelujah," hundreds of other artists have recorded it. Performances of the song have been watched millions of times on YouTube. I found a version, a pretty good version I have to say, by a kids' choir in Iceland.

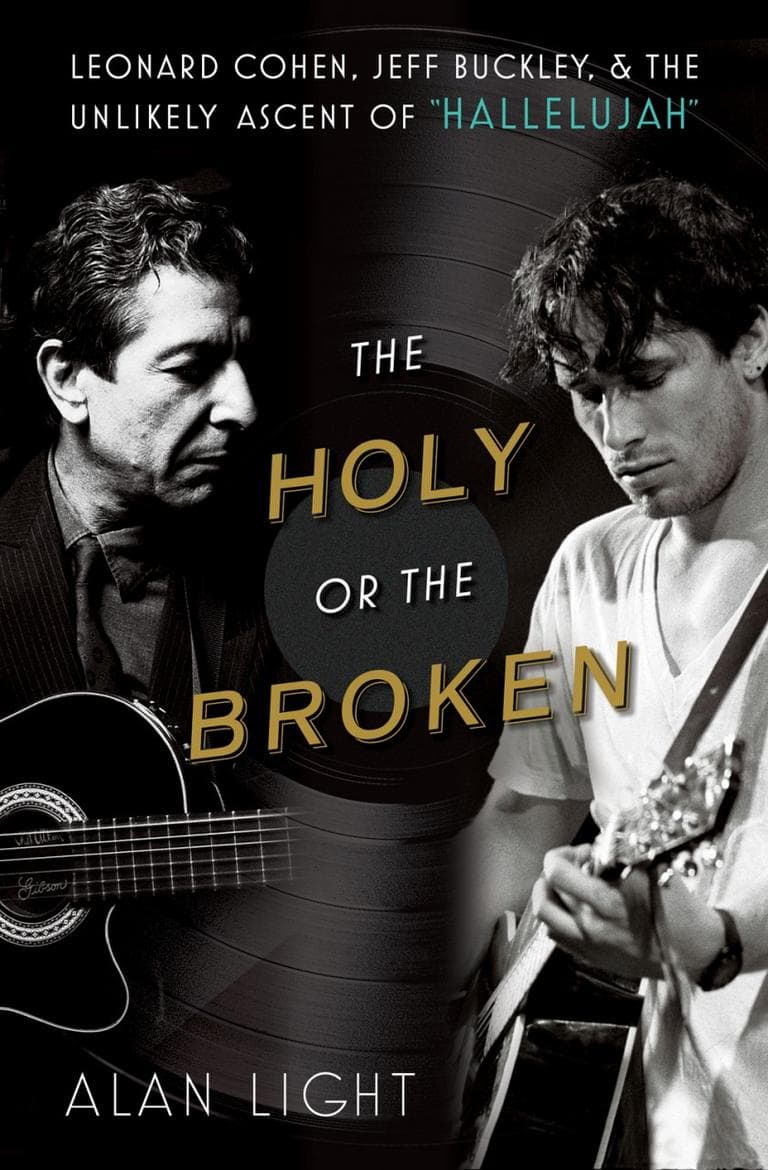

The story of how this once obscure Cohen song, originally rejected by his record label, became one of the most familiar songs in the world spins out in Alan Light's book "The Holy Or The Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & The Unlikely Ascent Of Hallelujah." (See book excerpt below)

Light told Here & Now's Robin Young that when Cohen first recorded "Hallelujah" in 1984, the timing wasn't right. It was 1984, a huge year for pop music, with Prince's "Purple Rain," Madonna's "Like A Virgin," Bruce Springsteen's "Born In The USA" and MTV dominating the world, and this music by a 50-year-old man didn't resonate.

But even when Cohen did eventually release "Hallelujah," it still didn't get any attention.

"None of the reviews of the record picked up on 'Hallelujah' at all," Light said. "So it's not like this thing was a gem that the label was too blind to see. Nobody could see it."

John Cale saw it, even though he had never heard of it until he saw Cohen perform the song. Cale recorded his version in 1991 for a Cohen tribute album, and that's the version millions of kids heard when they went to see the movie "Shrek."

But the artist who really put Hallelujah on the map was the late Jeff Buckley. He started playing it in his shows and recorded it in 1994.

Buckley died in 1997. He drowned while swimming in the Mississippi River in Memphis. He was 30. But his version of "Hallelujah" lived on.

[sidebar title="Hallelujah Covers" width="200" align="right"]Click to listen:

Bono

k.d. lang

Bon Jovi

Rufus Wainwright

Michael McDonald

Children's Choir in Iceland

What's your favorite version of Hallelujah? Let us know on our Facebook page.

[/sidebar]

It was part of the soundtrack after the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001. And as Light said, "it became the sad song," used during emotional scenes in TV shows such as "The West Wing."

But then the song took another turn in its history, when contestants started singing it on "American Idol," "X Factor" and "The Voice." This week, in response to the massacre in Newtown, "The Voice" opened the show with "Hallelujah." (Watch the YouTube video)

We didn't have time to include everything in our on-air interview with Alan Light. He told us something kind of funny when we talked about the "bad" versions of "Hallelujah." Among them is Bono's, recorded in 1995.

Light said he had already turned in his manuscript when he got the word that Bono was going to call him to talk about the song.

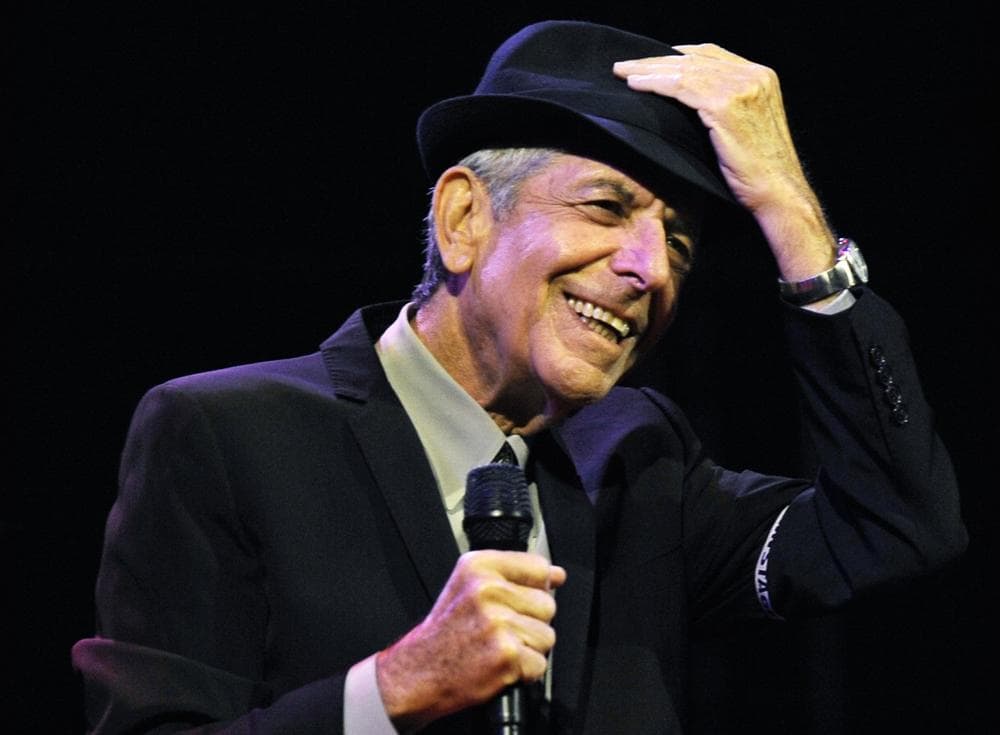

So bad versions and good, “Hallelujah” has taken on a life of its own, far beyond the song that Leonard Cohen recorded in 1994. But it’s also part of his new life. His career has been rejuvenated and he’s touring a lot. In fact he’s playing in Brooklyn tonight at the new Barclays Center.

I think you can count on him playing “Hallelujah.”

____Book Excerpt: 'The Holy or the Broken'

By: Alan Light____

Introduction The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum sits on the Columbia Point peninsula of Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. It is housed in a striking I. M. Pei building, situated in dramatic isolation on a reshaped former landfill.

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum sits on the Columbia Point peninsula of Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. It is housed in a striking I. M. Pei building, situated in dramatic isolation on a reshaped former landfill.

This brisk February Sunday in 2012, President Kennedy’s daughter, Caroline, is opening a ceremony by invoking one of her father’s speeches. “Society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him,” she quotes him as saying in a 1963 address at Amherst College, honoring Robert Frost. “The highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist, is to remain true to himself.”

The occasion is the inaugural presentation of a new award for “Song Lyrics of Literary Excellence,” given by PEN (Poets/Playwrights, Essayists/Editors, Novelists) New England. The award committee, chaired by journalist/novelist/ television executive Bill Flanagan, includes Bono, Rosanne Cash, Elvis Costello, Paul Muldoon (poet and poetry editor at the New Yorker), Smokey Robinson, Salman Rushdie, and Paul Simon. The first recipients of the award are Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen.

The honorees are both dressed in their latter-day uniforms: Berry in a sailor’s cap and windbreaker, Cohen in a dark suit with a gray shirt, topped by a fedora. In truth, the spotlight mostly stays squarely on eighty-five-year-old Berry. Paul Simon presents Berry’s award—which the event program says “reflect[s] our passion for the intelligence, beauty and power of words” and celebrates these songwriters for “their creativity, originality and contribution to literature”—with a heartfelt, slightly rambling speech, reciting some of the rock and roll pioneer’s most evocative lyrics, which Berry admitted at the time he couldn’t hear.

Costello performs an impassioned, slowed-down version of Berry’s “No Particular Place to Go,” and Flanagan reads a congratulatory e-mail from Bob Dylan, who calls Berry “the Shakespeare of rock and roll” (adding, “Say hello to Mr. Leonard, Kafka of the blues”). Instead of making a speech, Berry straps on Costello’s guitar and delivers a haphazard verse of “Johnny B. Goode.” The whole thing winds up with Costello and surprise guest Keith Richards—perhaps Chuck Berry’s greatest acolyte—swaggering through a glorious rendition of “The Promised Land,” with the beaming Rolling Stone reeling off three lengthy, hard-driving guitar solos as his idol pumps his fist in the front row.

In contrast to all that firepower, the presentation to Cohen is quiet and modest. Shawn Colvin sings a delicate, slightly nervous version of “Come Healing,” as Cohen leans forward in his seat and watches closely. At the end of the song, she knocks over her guitar when placing it back in its stand; Cohen graciously bends over and steadies the instrument before leaning in to give Colvin a kiss of gratitude.

Cohen’s own speech is brief and characteristically humble. With Dorchester Bay and the Boston skyline gleaming through the windows behind the podium, the elegant seventy-seven-year-old talks for less than two minutes— exclusively about Chuck Berry. His bass voice scarcely above a murmur, he says that “Roll Over Beethoven” is “the only exclamation in our literature that rivals Walt Whitman declaring his ‘barbaric yawp.’ ” He concludes with the thought that “all of us are just footnotes to the work of Chuck Berry.”

Salman Rushdie’s presentation to Cohen is a bit more expansive. “When we were kids, he taught us something about how it might be to be grown up,” the novelist says. He quotes a few lines from Cohen’s songs, and sums up his admiration by saying, “If I could write like that, I would.”

Several times, Rushdie speaks of the song for which Cohen is now best known, calling it simply “the great ‘Hallelujah.’ ” He describes the song as “something anthemic and hymnlike, but if you listen closely you hear the wit and jaundiced comedy.” He gets a laugh from the audience when, with a grin, he notes Cohen’s rhyme of “hallelujah” with “what’s it to ya,” alongside the lyric’s “other rhymes equally non-sacred.” Rushdie compares this “playfulness” with the work of poets W. H. Auden and James Fenton, and describes the song’s “melancholy and exaltation, desire and loss.”

When the hour-long ceremony is over, and the thousand or so audience members have filed out of the auditorium, perhaps Leonard Cohen allows himself a moment to smile and consider the irony. This song, which tormented him for years, only to wind up included on the lone album of his career that his record company refused to release, is now held up as “exemplify[ing] the highest standards of literary achievement.” What’s more, this turn of events is far from the most unlikely thing that has happened to “Hallelujah” along its almost three-decade-long journey.

“Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld / So I can sigh eternally,” Kurt Cobain once sang in tribute to the only songwriter, many believe, who belongs in a class with Bob Dylan. But “Hallelujah,” which first appeared on Cohen’s 1984 album Various Positions, has already had one of the most remarkable afterlives in pop music history. The song has become one of the most loved, most performed, and most misunderstood compositions of its time. Salman Rushdie’s description of the contrasts in the lyric holds true: Joyous and despondent, a celebration and a lament, a juxtaposition of dark Old Testament imagery with an irresistibly uplifting chorus, “Hallelujah” is an open-ended meditation on love and faith—and certainly not a song that would easily be pegged as an international anthem.

“Hallelujah,” however, has been performed and recorded by hundreds of artists—from U2 to Justin Timberlake, from Bon Jovi to Celine Dion, from Willie Nelson to numerous contestants on American Idol. It has been sung by opera stars and punk bands. Decades after its creation, it became a Top Ten hit throughout Europe and Scandinavia. In 2008, different versions simultaneously held the Number One and Number Two positions on the UK singles chart, with Cohen’s original climbing into the Top 40 at the same time.

“Hallelujah” has been named to lists of the greatest Canadian songs of all time and the greatest Jewish songs of all time (though in writing about the song for America: The National Catholic Weekly website, one minister mused that the singer’s melancholic worldview might indicate that he “has some Irish blood”). It plays every Saturday night on the Israeli Defense Forces’ radio network. It made the list of Rolling Stone’s 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, and, in a poll of songwriters by the British music magazine Q, was named one of the Top Ten Greatest Tracks of all time, alongside the likes of “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Born to Run,” and “Strawberry Fields Forever.”

According to Bono, who has performed “Hallelujah” on his own and with U2, “it might be the most perfect song in the world.”

It’s impossible to determine how many people have listened to a single given song. One way to gauge popularity these days is to look at views on YouTube, which has become the world’s leading on-demand music service. Totaling up the number of times “Hallelujah” has been watched on the site, it’s clear that we’re looking at a figure in the hundreds of millions: Performances by three different acts (Jeff Buckley, an all-star quartet of Norwegian singers, and Rufus Wainwright) have each been viewed roughly fifty million times. Cohen’s own renditions of the song have another thirty million views, and four more singers top out with over ten million apiece. The YouTube onslaught is participatory, as well—instrumental versions, for karaoke, have another ten million views.

“Hallelujah” served as a balm to a grieving nation when Jeff Buckley’s much-revered version was used for VH1’s official post-9/11 tribute video; as a statement of national pride at the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Olympic Games in Vancouver; and as the centerpiece of the benefit telethon that followed the earthquake in Haiti.

These occasions are not always a comfortable fit for such a complex and ambiguous set of lyrics. The verses—four in Cohen’s original, five in Buckley’s 1994 rendition that is often considered definitive—touch on the biblical stories of King David and Samson, though they are far from pious, offering such charged language as “I remember when I moved in you, / and the holy dove was moving too” and “all I ever learned from love / is how to shoot at someone who outdrew you.” Yet it also returns and lands, each time, on the reassurance and celebration of the title, which serves as a repeated, single-word chorus. The focus given to the hymnlike incantation of “hallelujah,” in contrast to the romantic and spiritual challenges evoked by the verses, raises an eternal pop music dilemma: Are people really paying attention to all the words, and does it matter?

Australian composer Andrew Ford expressed his reservations about the “ubiquity” of the song. He singled out its use at the memorial service for victims of the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009, when 173 people died and more than four hundred were injured as a result of fires in the state of Victoria. “Who knows why?” he wrote of the choice. “Perhaps because its one-word chorus sits in the context of a song that includes the line ‘Maybe there’s a God above’ it offered reassurance amidst doubt. Still, to have that response you would have to ignore most of the other words, and particularly those about spying a naked woman bathing on the roof, being tied ‘to a kitchen chair,’ and the verse about orgasm.”

Yet to Canadian country/pop chanteuse k. d. lang, one of the most celebrated interpreters of “Hallelujah,” the song has entered another realm, in which the public plays a more active role in its meaning. When she was asked to perform the song at the Vancouver Olympics, she recalls her own family’s response.

“My mom is eighty-eight years old,” said lang. “She lives in a seniors’ apartment and all her friends were like, ‘Oh, I love that song!’ I said, ‘Mom, do they know what the lyrics are about?’ And she goes, ‘I don’t think they listen to the lyrics; I think they just listen to the refrain.’ I think it’s very indicative of spirituality in general, that something as simple as saying ‘hallelujah’ over and over again, really beautifully, can redeem all the verses.

“Ultimately,” she concluded, “it’s a piece of music and it belongs to culture. It doesn’t belong to Leonard, it doesn’t belong to me, it doesn’t belong to anybody.”

The earliest manifestation of “Hallelujah,” however, could not have been more humble: When Cohen submitted the Various Positions album, on which “Hallelujah” appears, to Columbia Records in 1984, they refused to put it out. When the record was eventually released, the song was still generally ignored. To complicate things even further, Cohen immediately began changing and reworking the song in concert, confusing those few fans who were aware of it.

For a full ten years after its release, it gained extremely limited exposure through a few scattered cover versions. Jeff Buckley’s interpretation on his 1994 album, Grace, ultimately served as the pivot point for the song’s popularity, but even that recording took a number of years before it truly started to capture the public’s imagination.

Yet by the time “Hallelujah” had become a staple for such sentimental moments as the 2011 Emmy Awards “In Memoriam” segment (performed by the Canadian Tenors), for some it was a “Hallelujah” too far. New York magazine’s website live-blogged, “‘Hallelujah’ is on the artistic ban list. Sorry, Emmys.” A story on Salon.com decried the “criminal overuse of ‘Hallelujah.’ ” Indeed, the song has been included in so many movies and television shows over the years— The West Wing, ER, The O.C., House, on and on—that in 2009 Cohen himself suggested a moratorium on further soundtrack placements. “I think it’s a good song,” he said, “but too many people sing it.”

By 2012, he was a bit more circumspect about the situation. “Once or twice I’ve felt maybe I should lend my voice to silencing it,” he said to England’s Guardian newspaper, “but on second thought no, I’m very happy that it’s being sung.”

Somewhere along the way, “Hallelujah” reached the kind of rarefied status that only a handful of contemporary songs—“Imagine,” “A Change Is Gonna Come”—have achieved. Its presence in the world reaches far beyond the song itself, and serves as shorthand for some greater idea or emotion.

Paul Simon wrote another one of these modern hymns. “I would not have predicted that ‘Bridge over Troubled Water’ would be a song that would be kind of permanently there,” said Simon, sitting in the lobby of the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York, on a break from rehearsal for his 2011 tour supporting the So Beautiful or So What album. “People used to play it at their weddings, and now they play it at their funerals, state funerals—I heard it played when Ronald Reagan died. So that song has found a purpose and it will stay there, serving that purpose, until it’s no longer needed.”

Over the years, Simon noticed that Cohen’s composition gradually began to play a similar role, in its popularity and its uses. “‘Hallelujah’ started to be the ‘Bridge over Troubled Water’ alternative,” he said. “His song has that feel, but it’s also got somebody being tied down and having their hair cut off. But it moves people in the same way that ‘Bridge over Troubled Water’ does, and I’ve heard it sung by a lot of different people, really beautifully. It’s part of the mystery, that there are songs that are like that, and if you’re lucky enough to be the writer of the song—well, in a certain sense, if there’s such a thing as immortality, then there’s a little bit of immortality attached to that.”

Many latter-day “Hallelujah” fans, though, actually have no idea it’s a Leonard Cohen song; they assume that it was written by Jeff Buckley. Others think that it’s an ancient liturgical song, and are shocked when informed that it was written in the 1980s. Because it has reached so many more listeners through interpretation rather than through the author’s own performances, now it mostly just seems like it’s always been here.

Whether listeners know its origin or not, however, the mysterious imagery of “Hallelujah”—like many of Cohen’s writings, a blend of the sacred and the sensual—has rendered the song something of a musical Rorschach test. Singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile, who does not hesitate to refer to “Hallelujah” as “the greatest song ever written,” said that it provided her with the key for reconciling her Christian faith and her homosexuality. Carlile went through a period during which she slept with a boom box next to her bed at night; she would leave Jeff Buckley’s “Hallelujah” on repeat and let it play for eight or nine hours at a time.

“To me, it really outlined how people tend to misconstrue religion versus faith,” she said. “I felt that this song was, in a really pure, realistic way, describing what ‘hallelujah’ actually is. ‘It’s not a cry that you hear at night / It’s not somebody that’s seen the light’—‘hallelujah’ is not something that you shout out on Sunday in a happy voice; it’s something that happens in a way that’s cold and broken and lonely. And that’s how I was feeling at the time.”

For Alexandra Burke, winner of the 2008 X Factor in the UK, “to anyone who’s a Christian, that word “hallelujah”— full stop, that’s what you’re going to hear.” To the acclaimed, offbeat singer-songwriter Regina Spektor, “he’s using traditional Jewish stories and history, and having gone to yeshiva and studied those stories, all the biblical things are an extra place for my mind to go.”

“I got the sexuality in the song right away,” said Jon Bon Jovi. “The chorus is like the climax, the rest is like foreplay.” For Rabbi Ruth Gan Kagan, who has included “Hallelujah” in the Yom Kippur service at the Nava Tehila congregation in Jerusalem, “it’s a hymn of the heretic, a piyut [liturgical poem] of a modern, doubtful person.”

For some, it’s this ability of “Hallelujah” to contain multitudes, to embrace contradictions, that gives it such power. “I can’t think of another song that can be done so many different ways,” said Justin Timberlake, who performed it at the “Hope for Haiti Now” benefit telethon. “It’s a testament to the songwriting. The interesting thing that Leonard Cohen is able to do—which equates to some of my favorite actors—is that he never makes you choose what to feel. He just gives you, like, a three-pronged road, and you can take whichever path you like. That’s the beauty of all of his work.”

Maybe punk-cabaret artist Amanda Palmer, formerly of the Dresden Dolls, put it best. “Those verses are like the I Ching of songwriting,” she said, “and the chorus, that word hallelujah, is the ‘Get Out of Jail Free’ card.”

When Colin Frangicetto, a guitarist in the band Circa Survive, married his wife, Sam, in 2011, the bride walked down the aisle to a recording of “Hallelujah” performed as an instrumental by a string quartet. “We wanted a nontraditional wedding,” he said, “but there are always family members who are more religious or traditional or whatever, and I felt like this was in a way throwing them a bone, which is ironic. Even when you take away the words, there’s still a magical thing happening in the music. It’s simple, but with an extreme sophistication—and I think that’s the secret to most great songs, complexity hidden inside simplicity.

“It felt so fitting when committing our lives to each other,” Frangicetto continued. “Leonard Cohen said the song represented absolute surrender in a situation you can-not fix or dominate, that sometimes it means saying, ‘I don’t fucking know what’s going on, but it can still be beautiful.’ ”

Along with the rediscovery—more accurately, the discovery—of “Hallelujah” came a reconsideration of Leonard Cohen’s standing in pop music history. After being swindled by a manager and teetering on the edge of bankruptcy, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008 (at the ceremony, Lou Reed said that Cohen belonged to the “highest and most influential echelon of songwriters”) and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2010. He has received the Prince of Asturias Award, the highest literary honor granted by Spain, and the Glenn Gould Prize in his native Canada.

A lengthy world tour, during which he turned seventy-five, saw him sell out stadiums across Europe, headline the massive Glastonbury and Coachella festivals, and play to millions of fans, of all ages. After not performing on stage for fifteen years, between May 2008 and December 2010 Cohen trooped through 246 marathon shows, to rapturous crowds and rave reviews.

In January 2012, Cohen released Old Ideas, his first new studio album in eight years. The record debuted in the Number One position in nine countries, and in the Top Five in eighteen more. In the U.S., where none of his previous albums had ever reached the Top 50 of the charts, Old Ideas debuted at Number Three. Tickets for the tour that he announced for the second half of 2012 sold rapidly across Europe and the States. Propelled in part by the ascendance of “Hallelujah,” Cohen, long considered a cult artist, was finally welcomed into the pantheon of rock stars in his eighth decade.

Like Cohen’s ultimate popular acceptance, the impact of the song was only realized over time. In fact, the trajectory of “Hallelujah” seems unprecedented; it is perhaps the only song that has become a worldwide standard over the course of a gradual climb spanning several decades. Only after former Velvet Underground member John Cale recorded a rearranged version of the song in 1991, which was in turn covered by the tragic young rocker Buckley a few years later, did “Hallelujah” truly begin its improbable, epic voyage.

Furthermore, in becoming Buckley’s signature performance, it eventually helped the gifted but doomed artist earn a legacy commensurate with his talent: While the Grace album, the single studio record he released in his abbreviated life, only peaked at a disappointing Number 149 when it was released in 1994, it was certified gold in 2002 and—as a Buckley cult grew and expanded over the years— has gone on to sell several million copies around the world.

The notion of a “standard”—a song that is freed from its original performance or context and seeps into the general consciousness, where it is interpreted frequently and diversely—defined American pop music for decades. Songs from Broadway shows or Hollywood movies were the basis of most singers’ repertoires, from giants like Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra to local saloon singers. But this structure was pretty much crushed in the 1960s by the advent of the Beatles and Bob Dylan. Of the numerous upheavals these artists set in motion, perhaps the greatest revolution was the idea that singers should also be songwriters, and that their work expresses something specific and personal to them.

(It’s fascinating to see the aging members of rock’s Greatest Generation, the very ones who made up new rules and redefined the job of the pop singer, being drawn to the music that preceded them, and trying on the role of interpretive singers, whether it’s Paul McCartney and Rod Stewart tackling pop songs from the ’40s or Bruce Springsteen and Neil Young recording traditional folk material.)

R&B and country, genres that still largely maintain the traditional separation between singers and songwriters, have continued to produce occasional standards, at least within their own communities; songs such as “I Believe I Can Fly,” “I Hope You Dance,” or “I Will Always Love You” become part of the social fabric, turning up at piano bars, proms, first wedding dances, talent shows. But since such transitional landmarks as “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Yesterday,” post– rock-and-roll pop music has seen few songs transcend their original recordings. Even “Imagine,” though frequently performed in public settings, will always be so closely tethered to John Lennon’s original recording that it doesn’t have the same freedom and adaptability of older compositions. Furthermore, every one of these examples began spreading through the culture immediately—it was instantly clear that these were special songs that spoke to wide-ranging audiences.

Yet “Hallelujah” is different. Against all odds, it is now unquestionably a modern standard, perhaps the only song that has truly earned that designation in the past few decades. It appears in heavy metal shows and homemade videos by grade-schoolers, cartoons and action movies, Dancing with the Stars and religious services. It has reached a place where, for better or for worse, it is universal—even, as Paul Simon noted, immortal.

Rufus Wainwright, whose recording of the song is one of the most popular of them all, compared “Hallelujah” to compositions with an even longer history than those of the Great American Songbook, like classics by George Gershwin or Cole Porter. “With something like Stephen Foster’s song ‘Hard Times,’ it kind of shoots out and becomes this timeless ballad that is very appropriate at all times. And I think ‘Hallelujah’ has that ability to be released from its shackles, and every songwriter aims for that.

“It might seem odd to most people,” Wainwright continued, “but for me, being a classical music fanatic, it’s kind of the way things went. Schubert’s ‘The Trout’ or Ravel’s ‘Boléro’—they didn’t have records back then, and people had to disseminate sheet music and sing it or play it themselves. In a strange way, ‘Hallelujah’ followed a very traditional path that songs used to take. It’s encouraging that certain songs can still have their own lives and that they don’t have to be necessarily attached to a persona, because there was a time when the songwriter wasn’t necessarily the front man. I think that’s the way things should be—I’m a songwriter, so I’m on the song’s side.”

Wainwright also pointed out that, of course, the title and chorus of the song connect it to traditions and emotions going back to some of our earliest written history. “ ‘Hallelujah’ has been a pretty popular thing for a long time,” he said, “whether it’s the ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ or Ray Charles’s ‘Hallelujah, I Love Her So.’ It has deep, deep roots in the human psyche. So I think it can relate a lot to different situations, whether it’s about war, about peace or love or hate or whatever; it’s this unifying expression of human existence, in a weird way—hallelujah—it’s just life, in a sense.”

“In a lot of ways, musicians covering ‘Hallelujah’ feel the way doing the ‘To be or not to be’ speech would feel for an actor,” said Regina Spektor. “You become part of a tradition. The words are so expressive, the melody is so transcendent, you get to be in this incredible soliloquy and have this incredible moment. It’s not like, ‘Oh, Laurence Olivier did that, so no one else can.’ ”

How did this unconventional song attain such popularity, in such an incremental fashion, over such an extended period of time? Why did it go from being a forgotten album cut by a respected but generally unknown singer-songwriter to a track on Susan Boyle’s 2010 Christmas record?

Appropriately enough, I started to think about “Hallelujah,” which seems to me to be, at its heart, a challenge to personal and spiritual commitment, on Yom Kippur. Congregation Beit Simchat Torah (CBST) hosts perhaps the largest High Holiday gathering in New York City: The gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender synagogue is one of the last congregations in Manhattan that holds open services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, not requiring attendees to purchase an annual membership, or even advance tickets, to attend. As a result, lots of stray Jews, music and arts professionals, journalists, and the like find their way there, and the 2010 Kol Nidre service, held in the enormous Jacob Javits Convention Center on the west side of Manhattan, drew some four thousand people.

Kol Nidre is the introductory service on the holiest day of the Jewish year, the Day of Atonement. CBST Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum—one of Newsweek’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis in America” and always a remarkable speaker, who particularly rises to the challenge of the major holidays and events—gave her sermon, focusing on an interview that Woody Allen had given that week to the New York Times in which he said that he wished he could be a spiritual person, because it would make his life easier. After challenging the filmmaker on this premise, the rabbi ceded the stage to the CBST choir, led by Cantor Magda Fishman, which delivered a stunning version of “Hallelujah.”

The unique composition of the congregation made it a little less weird to hear “She tied you to a kitchen chair / she broke your throne, she cut your hair” in this sacred context. But the notion of this song serving as the emotional peak of the service, crackling through thousands of listeners— who were clearly familiar with the song, many weeping as it crescendoed—made it eminently clear that “Hallelujah” had reached a singular altitude, and was a phenomenon worthy of some extended consideration.

When I approached Leonard Cohen about this project, he gave me his blessing to proceed through his manager, but declined requests to talk about “Hallelujah.” And really, who can blame him? Aside from the fact that he seldom does interviews, even on the rare occasions when he has an album to promote, why would he want to disturb the mythology around this song? Having watched his composition un-expectedly attain such iconic status, largely without his own involvement, Cohen is wise to allow the song to retain as much mystery as possible.

In a 2008 BBC Radio 2 documentary about “Hallelujah” titled The Fourth, The Fifth, the Minor Fall, Guy Garvey of the British band Elbow recalled watching Cohen perform the song at the Glastonbury Festival. From his spot on the side of the stage, Garvey said that just before starting the introduction, Cohen turned to his band and said, “Let her go!” And that’s just what’s he’s done with this astonishing song—he let it go, to find its own way, through one of the most unexpected and triumphant sagas in the history of popular music.

Excerpted from the book THE HOLY OR THE BROKEN by Alan Light. Copyright © 2012 by Alan Light. Reprinted with permission of Atria Books.

Guest:

This segment aired on December 20, 2012.