Advertisement

10 Years After Invasion, A Look At Iraq War Legacy

Resume

More than 50 people have been killed in a wave of bombings across Baghdad and nearby towns, according to Iraqi officials.

The attacks coincide with the 10th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, which started before dawn on March 20, 2003.

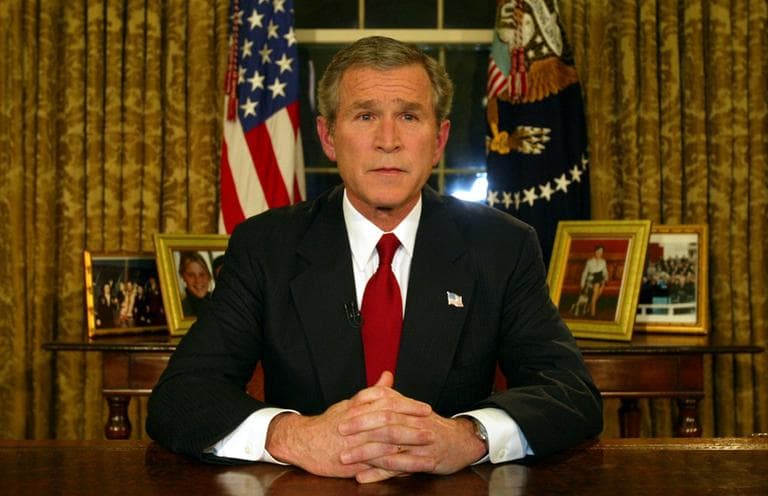

On March 19, 2003, President George W. Bush spoke from the Oval Office and said, "On my orders, coalition forces have begun striking selected targets of military importance to undermine Saddam Hussein's ability to wage war."

Hussein's regime was quickly toppled and he was eventually caught and executed. The U.S. finally pulled its combat troops out of the country in December 2011.

So what's the legacy of the Iraq War?

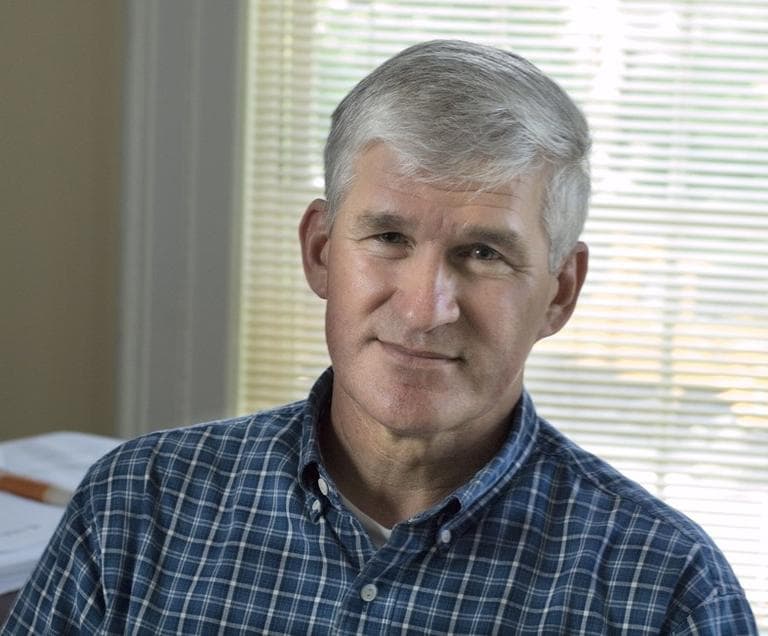

Andrew Bacevich is a professor of history and international relations at Boston University and also a retired Army colonel and veteran of the Vietnam War.

He opposed the war in Iraq before it started, and before his son, Army First Lieutenant Andrew Bacevich, Jr., was killed in there in 2007.

An updated edition of Bacevich's book, "The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced By War," is being published this month (see excerpt below).

Recent pieces by Andrew Bacevich:

- Washington Post: Ten years after the invasion, did we win the Iraq war?

- Harper's: A Letter to Paul Wolfowitz

Previous interviews with Andrew Bacevich:

- Analyst: David Petraeus Is No General Patton (Nov 2012)

- Honoring Iraq War Vets (Feb 2012)

- The End Of America’s Great Expectations (Dec 2011)

Do you remember where you were when the U.S. invaded Iraq? What were your feelings about it then? Tell us in the comments or join the conversation on Facebook.

____Book Excerpt: 'The New American Militarism'

By: Andrew J. Bacevich____

Afterword: Militarism Entrenched

The first edition of this book appeared when Americans were experiencing a moment of profound disorientation. In the wake of 9/11, widespread confidence in U. S. military power had invested the George W. Bush administration’s “global war on terrorism” with a modicum of plausibility. In pursuit of a righteous cause, nothing would or could stop American warriors in their quest to vanquish evil. So Americans believed and expected, with early returns ever so briefly vindicating such expectations. Yet by 2005, when The New American Militarism became available, victory as such appeared increasingly unlikely. Meanwhile, the costs (not to mention the moral complications) entailed by campaigns undertaken in Afghanistan and Iraq were turning out to be vastly larger than anticipated.

President Bush’s inability to make good on the promises implicit in his war on terror yielded large-scale political consequences. In 2006, capitalizing on widespread dissatisfaction with administration war policies, Democrats regained control of Congress. Two years later, a charismatic candidate with a thin résumé captured the presidency itself. Barack Obama couldn’t match the credentials of more seasoned aspirants to the White House. But he unlike they had voiced principled opposition to the Iraq War since its inception—and that made the difference.

Obama’s campaign had been all about “Hope”—hope for change and for a new beginning. Nowhere were those hopes greater than with regard to U. S. military policy. Whether fairly or not, George W. Bush left office tagged as a war-monger, and an incompetent one at that. Obama’s supporters expected him to reverse course, weaning the United States away from its penchant for military adventurism. Such hopes were not confined to Americans alone: based entirely on his expressed aspirations rather than any actual achievements, the Nobel Committee awarded Obama its 2009 Peace Prize.

In the event, the choice turned out to be a deeply ironic one. Indeed, more than anything else, the massive gap between what the Nobel Committee (and many millions of others) expected of Obama and what actually ensued with regard to U. S. military policy justifies a second edition of this book. American militarism persists.

To unveil his administration’s new national security strategy in early January 2012, President Obama made the short trip across the Potomac from the seat of power of the executive branch to the seat of power of America’s armed forces. Presidents visit the Pentagon infrequently. In matters relating to national security, they typically conduct business at the White House, receiving high-ranking military officers and senior defense officials rather than calling on them. Yet Obama’s advisors had selected this out-of-the-ordinary venue to make a point. That point was identical in intent (if less theatrical in execution) to the one that had inspired a previous set of advisors to land their president on an aircraft carrier in order to proclaim a war won: to highlight the president’s role as commander-in-chief and to endow his words with added weight and authority.

In his prepared remarks, Obama depicted the occasion as a momentous one, announcing that “we’re turning the page on a decade of war.” “Turning the page” meant it was time to reassess the size, stationing, and configuration of U. S. forces. For top members of his administration, doing so had required “asking tough questions, challenging our own assumptions and making hard choices.” The president briefly sketched out what making hard choices entailed. The Pentagon was going to rid itself of “outdated Cold War-era systems so that we can invest in the capabilities that we need for the future.” A “leaner” military establishment would be one result. Yet the president took pains to guarantee that U. S. forces would remain capable of handling “the full range of contingencies and threats.” He promised improvements across the board: in “intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, counterterrorism, countering weapons of mass destruction and [operating] in environments where adversaries try to deny us access.”

Unquestioned and unchallengeable military superiority was going to remain a hallmark of American statecraft. “The United States of America is the greatest force for freedom and security that the world has ever known,” Obama asserted. “And in no small measure, that’s because we’ve built the best-trained, best-led, best-equipped military in history—and as Commander-in-Chief, I’m going to keep it that way.”1

Of course, critics wasted no time in disputing the president’s characterization of his proposed strategy. In their view, Obama was stripping the nation’s defenses and forfeiting its position of global leadership. “This is a lead-from-behind strategy for a left-behind America,” charged Representative “Buck” McKeon, Republican of California and chairman of the House Armed Services Committee. He dismissed Obama’s plan as “retreat from the world in the guise of a new strategy.”2 According to Max Boot, American journalism’s preeminent proponent of militarism, the president was launching the United States on a “suicidal trajectory.”3 Hawkish writers manning the ramparts at the Weekly Standard concurred. In his brief Pentagon announcement, Obama had issued “an order to retreat.” The administration’s new strategy was “a bright green light to our enemies and a flashing red one to our friends and allies.” By consciously and intentionally denuding America’s defenses, Obama had made “a choice for weakness, a choice that will invite war, [and] a choice for American decline.”4

In fact, both Obama’s claims of big change and the fevered rhetoric of his critics fell equally wide of the mark. The president’s reference to “turning the page” was, in fact, a model of artful precision. For the actual purpose of the administration’s new strategy (and of the president’s Pentagon appearance) was not to close the books on war, but in turning the page, to open a new chapter. The decade-long conflict (or more accurately, conflicts, since there were more than one) to which Obama referred would not end in the foreseeable future. Indeed, at the moment the president spoke, the new chapter had already commenced.

Among the few to appreciate the charade was the Washington Post’s Walter Pincus. The Obama approach to national security preserved far more than it changed, and much of what it was preserving was deeply problematic. “Has President Obama adopted George W. Bush’s ‘policeman of the world’ approach to the fight against terrorism?” the veteran reporter asked.5 With qualifications duly noted, Pincus answered that question in the affirmative. Stylistically, Obama’s approach might differ from Bush’s.

But substantively, the two shared the same DNA. To a far greater extent than either his defenders or his critics were wont to admit, Obama was taking the country further down the path toward permanent war that his predecessor had blazed.

Indeed, in his Pentagon presentation, Obama made a point of endorsing the existing fundamentals of U. S. military posture and policy. He offered an unambiguously upbeat assessment of what the previous decade of war had wrought. A few regrettable missteps aside, it had proven to be a smashing success.

[A]round the globe we’ve strengthened alliances, forged new partnerships, and served as a force for universal rights and human dignity.… [W]e’ve succeeded in defending our nation, taking the fight to our enemies, reducing the number of Americans in harm’s way, and we’ve restored America’s global leadership. That makes us safer and it makes us stronger.

It followed from this record of success that any new strategy should entail the tweaking of existing practices rather than their wholesale abandonment. So with regard to resources, the president called for judicious trimming, not retrenchment, promising that “the defense budget will still be larger than it was toward the end of the Bush administration.” With regard to forces, he emphasized not downsizing but enhanced capabilities. Touting a military that would be “agile, flexible and ready” and require a “smaller footprint,” the president revived language that Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld had once employed to describe his vision for transforming U. S. forces. With regard to its global posture, adjustments might be in the offing, but the United States military was not coming home. It was simply reorienting its attention on prospective new threats, notably the putative Chinese challenge in the Pacific. Above all, the president vowed that there would be no backsliding.

[W]e have to remember the lessons of history. We can’t afford to repeat the mistakes that have been made in the past—after World War II, after Vietnam—when our military was left ill-prepared for the future. As Commander in Chief, I will not let that happen again. Not on my watch.

What had already occurred on Obama’s watch was notable. Fulfilling a promise he had made as a candidate, the president ended direct U. S. military involvement in the Iraq War, effectively writing off more than eight years of costly military exertions to determine Iraq’s fate. Yet the upheaval touched off by Operation Iraqi Freedom continued and, in the wake of the U. S. military withdrawal, showed signs of worsening. Although the American phase of the Iraq War may have ended, the war itself had not. Even so, the Obama administration—and the majority of the American people—did their level best to ignore the evidence suggesting that Iraq itself remained unfinished business.

Then there was Afghanistan. Shortly after taking office, President Obama had committed an additional 17,000 U. S. troops to the war that he had charged his predecessor with neglecting. Yet this proved only the beginning. Near the end of his first year in office, just a week prior to accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, Obama ordered a further escalation in Afghanistan, one that mirrored Bush’s 2007 “surge” in Iraq. For a brief interval, Obama even flirted with the nation-building-with-guns approach (formally known as “counterinsurgency”) that Bush had pursued in Iraq. As Bush had done in Iraq, the president sought through the use of violence to determine Afghanistan’s fate, with similarly inconclusive results.

Notably, Obama’s escalation in Afghanistan also included a spatial dimension. He widened that war considerably, incorporating the frontier regions of neighboring Pakistan into the zone of military action. Almost exactly forty years earlier, without Congressional approval and while keeping the American public in the dark, President Richard Nixon had initiated the bombing of Laos, which thereby became an adjunct theater of the much larger Vietnam War. In comparable fashion, without Congressional authorization and with only the most cursory public notification, Obama initiated a campaign of attacks directed against suspected Taliban and al Qaeda operatives seeking sanctuary in Pakistan, which thereby became an adjunct theater of the much larger Afghanistan War. Whereas Nixon employed a blunt instrument—B52s dropping massive bomb loads—Obama relied on missile-firing drones and commando raids.

Failing to prevent North Vietnamese infiltration into South Vietnam, Nixon’s secret bombing of Laos succeeded mostly in creating chaos. Failing to prevent cross-border movement in and out of Afghanistan, Obama’s quasi-secret attacks into Pakistan served mostly to stoke anti-American outrage and undermine Pakistani stability. Yet whereas Washington in the 1970s attached minimal strategic importance to Laos, nuclear-armed Pakistan reputedly ranks today in the top-tier of countries in which the United States has a vital interest. Obama’s single-mindedness—his confidence in the efficacy of force to address proximate problems while disregarding secondary consequences—rivaled Richard Nixon’s.

In Pakistan and elsewhere, drone attacks employed pursuant to a campaign of targeted assassination became the signature of Obama’s new way of war. In February 2011, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates categorically ruled out any further experiments with the Bush administration’s invade-occupy-and-transform paradigm, declaring that “any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia or into the Middle East or Africa should ‘have his head examined.’”6 Most members of the public had long since reached a similar conclusion. In effect, Gates validated such sentiments and invested them with the force of policy. Apart from a few diehards—writing in the Weekly Standard, William Kristol accused Gates of “undercutting the troops’ mission [in Afghanistan] as though he’s resigned to their failure”—this Gates Doctrine evoked little dissent.7

Yet a reluctance to commit large-scale land armies did not signify a reluctance to use force. On that score, Obama and his team left little room for doubt. Meanwhile, the American people, despite having lost their stomach for big wars, proved more than willing to indulge the administration’s appetite for smaller ones, albeit more out of indifference or inattention than genuine enthusiasm.8

Obama’s penchant for targeted assassination found application not only in Pakistan but also in places like Yemen and Somalia. In Libya, with allied support, the United State employed airpower on a more sustained basis to help rebels overthrow the regime of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. With minimal fanfare, the administration also set out to establish “a constellation of secret drone bases” in and around the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa—new platforms from which to conduct attacks against Islamic radicals wherever they might be found.9

As under Bush so under Obama: the United States claimed the exclusive prerogative of striking wherever it needed whenever it chose to do so. And under Obama it continued to act accordingly. This is what turning the page on a decade of war signified.

Notably absent, at least in the halls of government, has been any serious analysis of what a decade of war has actually wrought, and at what price. In terms of outlays, the facts are indisputable. After 9/11, the U. S. military budget—already far and away the world’s largest—grew by leaps and bounds. Growth continued without interruption when Obama succeeded Bush. By 2011, Pentagon spending in constant dollars surpassed what it had reached at any time during the Cold War. Even excluding the costs of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, U. S. military spending grew by nearly 50 percent in the decade following 9/11. Regarding war costs, a comprehensive study conducted at Brown University estimated the bill at between $3.2 and

4 trillion—and counting.10 As for the human toll, as of 2011, the Brown University researchers estimated that conflicts launched in the wake of 9/11 had displaced some 7,800,000 persons and killed another 236,000, among them over 6,000 American troops.11

What has this vast outlay of treasure and this harvest of death and human suffering purchased? Simply put, not victory.

George W. Bush’s premature claim of mission accomplishment in Iraq in May 2003—much derided after the fact—had accurately reflected prevailing American expectations of how wars were supposed to end: neatly and decisively. Once engaging the enemy, superior U.S. forces would quickly prevail, with the conflict concluding on terms consistent with whatever purposes the commander-in-chief had enunciated at war’s outset. Outcomes, in short, were expected to express Washington’s will, thereby affirming the supremacy of American power.

The actual experience of war after 9/11 demolished all such expectations. Elaborating on the Obama national security strategy shortly after the president’s Pentagon appearance, JCS chairman General Martin Dempsey could describe the United States military as a force “that can win any conflict, anywhere.” Yet making that claim required Dempsey to sidestep this disturbing fact: The United States military had emphatically not won the conflicts in which he himself had recently participated.12

The truth, however unwelcome, is that since 1945 U.S. forces have not achieved a conclusive success in any contest on a scale larger than policing actions such as the 1983 intervention in Granada or the 1989 invasion of Panama. In terms of tactical proficiency and technological sophistication, the military establishment over which Dempsey presided remains without peer: No one else even comes close. To judge by operations such as the one that killed Osama bin Laden in May 2011, America’s elite warriors are arguably the best the world has ever seen. Yet even if U. S. forces possess the ability to win just about any fight, their capacity to win a serious war is subject to considerable question. When it comes to translating military might into desired political outcomes—the nominal rationale for war—they have floundered.

As expectations of triumphant short wars give way to the reality of indecisive long wars, the troops sent to wage those wars demonstrate an admirable, if not entirely untarnished ability to cope, adapt, and endure.13 Rotation back and forth between home stations and combat theatres has become routine. For their part, senior leaders struggle to explain this new reality of wars that drag on interminably. Shoring up their own claims of professional mastery requires that they devise an explanation that avoids any admission of their having failed to anticipate or grasp the character of modern war.

In the vanguard of this effort was General George Casey. As senior U. S. commander in Baghdad, Casey struggled unsuccessfully for two years to conclude that war. Upon his return from Iraq in 2007, he ascended to the position of U S. Army chief of staff and shortly thereafter began promoting the idea that the United States had become enmeshed in what he called an “era of persistent conflict.” Ever since the outbreak of the Korean War, which had caught it unprepared, the army had sought to hold itself in constant readiness for what it expected to be occasional wars. The implicit assumption was that armed hostilities represented an abnormal condition. Casey’s persistent conflict formulation now junked that assumption. War was no longer a sometime thing. It had become, Casey told the House Armed Services Committee in April 2008, “the new normal.” Furthermore, it was now incumbent upon the army to “remake itself with that in mind.”14

In the Pentagon, an implicit new assumption prevailed: for the United States, war had become inescapable. The result was to invert the Melian Dialogue. The great historian Thucydides believed that with power came the possibility of choice while those lacking power were obliged to bend to circumstance. “The strong do what they can,” he famously wrote, “and the weak suffer what they must.”15 The U. S. military of the 21st century is ostensibly the world’s strongest; yet senior officers such as General Casey believe that that it has become the nation’s fate to suffer permanent war. The United States apparently has no choice in the matter.

An inability even to conceive of a plausible alternative to war suggests a profound failure of strategic imagination. Yet this aptly describes the condition besetting Washington in the decade after 9/11. By accepting war as a permanent condition, senior officials in the Pentagon and elsewhere in the national security bureaucracy forfeited whatever modest creative capacity they may once have possessed. As a policy priority, conflict management took precedence over conflict avoidance or termination. In the decade after the 9/11 attacks, peace had “become something of a dirty word in Washington foreign-policy circles.” So wrote Greg Jaffe, the Washington Post’s military correspondent, adding with considerable justification that “This is the American era of endless war.”16 Jaffe thereby aptly summarized what vast expenditures of blood and treasure had purchased: victory had become a chimera; the acceptance of endless war was now America’s destiny.

This new normal has somewhat disconcerting implications for the relationship between American soldiers and the nation they serve. If it were possible, acceptance of war as an open-ended enterprise elevated further the popular standing of those saddled with the burden of waging war. In the eyes of the American people, “the troops” could do no wrong. To the last man and woman, they were heroes, to whom the nation owes an immense debt of gratitude. Making good on that debt—meeting the needs of veterans and of forces in the field—constitutes a sacred obligation. Even in a Washington where Republicans and Democrats agree on little else, this proposition commands something approximating unanimous support.

In some quarters, however, the suspicion developed that American civil-military relations were not as rosy as they appeared. How authentic were the expressions of gratitude that Americans showered on those who wore the uniform? “Thank you for your service.” The functional equivalent of the store clerk’s “Have a nice day” after completing a sale, this stock phrase creates the illusion of a relationship where none actually exists. Imposing no obligation, such expressions of appreciation for soldiers serve chiefly to gratify the speaker, lionizing the troops as an exercise in self-congratulations. Soldiers were not slow to figure this out.

The Great Recession that staggered the American economy beginning in 2008 created heightened awareness between the well-to-do and the rest of the country. On the one hand were the members of the “1 percent”—the very rich who just kept getting richer. On the other hand were the “99 percent”—the vast majority of people struggling to get by. For a brief interval, this gap seemed to define some essential and troubling truth to American politics and society. Less noted, but arguably even more acute, is another gap. This is the division between the 1 percent who serve and sacrifice in an era of open-ended war and remainder of citizens who carry on as if there were no war. James Wright, former Marine and former president of Dartmouth College, put the matter succinctly. “We pay lip service to our ‘sons and daughters’ at war,” he observed, “even if the children of some 99 percent of us are safely at home.”17 The “sons and daughters” sent in harm’s way weren’t ours in any literal sense. To pretend otherwise was unseemly.

Discomfort with this civil-military gap began gradually to make its appearance. In a Time magazine cover story in November 2011, correspondent Mark Thompson captured the growing unease. “The U.S. military and American society are drifting apart,” he wrote.

[T]roops in all the military services sense it, smell it—and talk about it. So do their superiors. We have a professional military of volunteers that has been stoically at war for more than a decade. But as the wars have droned on, the troops waging them are increasingly an Army apart.18

To camouflage this divide, Americans have invented rituals and made gestures, with corporate American quick to seize what it saw as a marketing opportunity. In short order, “Proudly Serving Those Who Serve” joined Anheuser Busch’s array of advertising slogans. “Here’s to the heroes,” the ad copy cheerfully burbled. “Great times are on deck.” For every home run hit during the 2011 major league baseball season, the nation’s leading brewer promised to donate $100 “to an organization that helps the families of fallen soldiers.” Here was patriotism served in a frosty mug: “Please raise your Budweiser and join us in honoring those who keep our nation safe and free every Thirst Inning.”19 Bud’s competitors lagged only slightly behind. “Give a veteran a piece of the High Life,” was the Miller Coors Brewing Company’s riposte. “For every High Life cap or tab you drop off at participating retailers or mail in, Miller High Life will donate 10¢ toward High Life Experiences for returning vets.” Money raised was going to defray the costs of soldier attending sports events and concerts, where beer was sure to be available for purchase. “Live the High Life. Give the High Life.”20

The sympathies of Mark Thompson and other journalists lay with the overworked and much-exploited troops. But some sensed in this civil-military gap more insidious implications. Todd Purdum was among them. “Increasingly,” he wrote in Vanity Fair, “there exist two societies in America.” The first Purdum depicted as “a military class, strongly religious, politically conservative, drawn disproportionately from the South and from smaller towns and areas of limited economic opportunity, including the inner cities.” The other he described as “an untouched civilian class consisting of everyone else, who wouldn’t know a regiment from a firmament or an M16 from a 7-Eleven.” The division of America into two camps had already produced pernicious results. “The civilian class can deploy the warriors at will, knowing that most Americans will remain unaffected. In turn, the military class can demand what it wishes, knowing that the civilians have no standing to resist.”

Here was an alternative explanation for General Casey’s era of persistent conflict. With the creation of its much-celebrated All-Volunteer Force and with its abandonment of the citizen-soldier tradition, Purdum continued, the United States had acquired “something that the country didn’t have in the past—a large and permanent warrior caste.”21 The state could employ that caste as it wished.

Perhaps a permanent warrior caste is just what a nation facing persistent conflict needs. Robert Gates for one wasn’t so sure. Visiting West Point shortly after stepping down as secretary of defense, he shared his reservations with the assembled cadets. The gap between the military and society was unhealthy, in his view. Among other things, it was fostering in the ranks a sense of moral superiority, members of the armed forces persuading themselves that they “adhered to a set of standards and values that is better than the civilian sector.” Gates worried about the emergence of “a cadre of military leaders that politically, culturally, and geographically have less and less in common with the majority of the people they have sworn to defend.” Down that road, even if in the far distance, lay the temptation of praetorianism.22

The obvious antidote to the dangers posed by a warrior caste set off from society is to reconstitute the tradition of the citizen-soldier. This, however, neither Gates nor any other figure of prominence in either American political life or the American military profession has ventured to suggest.

The “standing army” created in the wake of Vietnam at least in part to end the divisions created by Vietnam has now become sacrosanct, cherished by the state as an instrument for projecting power and by the country at large as a convenient device for dodging responsibility. Whether either party to this arrangement actually stands to benefit in the long run remains unclear. This much alone is certain: the attitudes and arrangements giving rise to the new American militarism remain intact and inviolable.

Excerpted from the book NEW AMERICAN MILITARISM: HOW AMERICANS ARE SEDUCED BY WAR, updated edition, by Andrew J. Bacevich. Copyright © 2005, 2013 by Andrew J. Bacevich. Reprinted with permission of Oxford University Press.

Guest:

- Andrew J. Bacevich, author of "The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War."

This segment aired on March 19, 2013.