Advertisement

Louisville Remembers A Tumultuous Time 60 Years Ago

ResumeThis year, Louisville, Kentucky, has been marking the anniversary of a touchstone event in the civil rights era. It started 60 years ago when white activists, led by Carl and Anne Braden purchased a home on behalf of a young black family. As Rick Howlett of Here & Now contributing station WFPL reports, that act touched off weeks of racial violence.

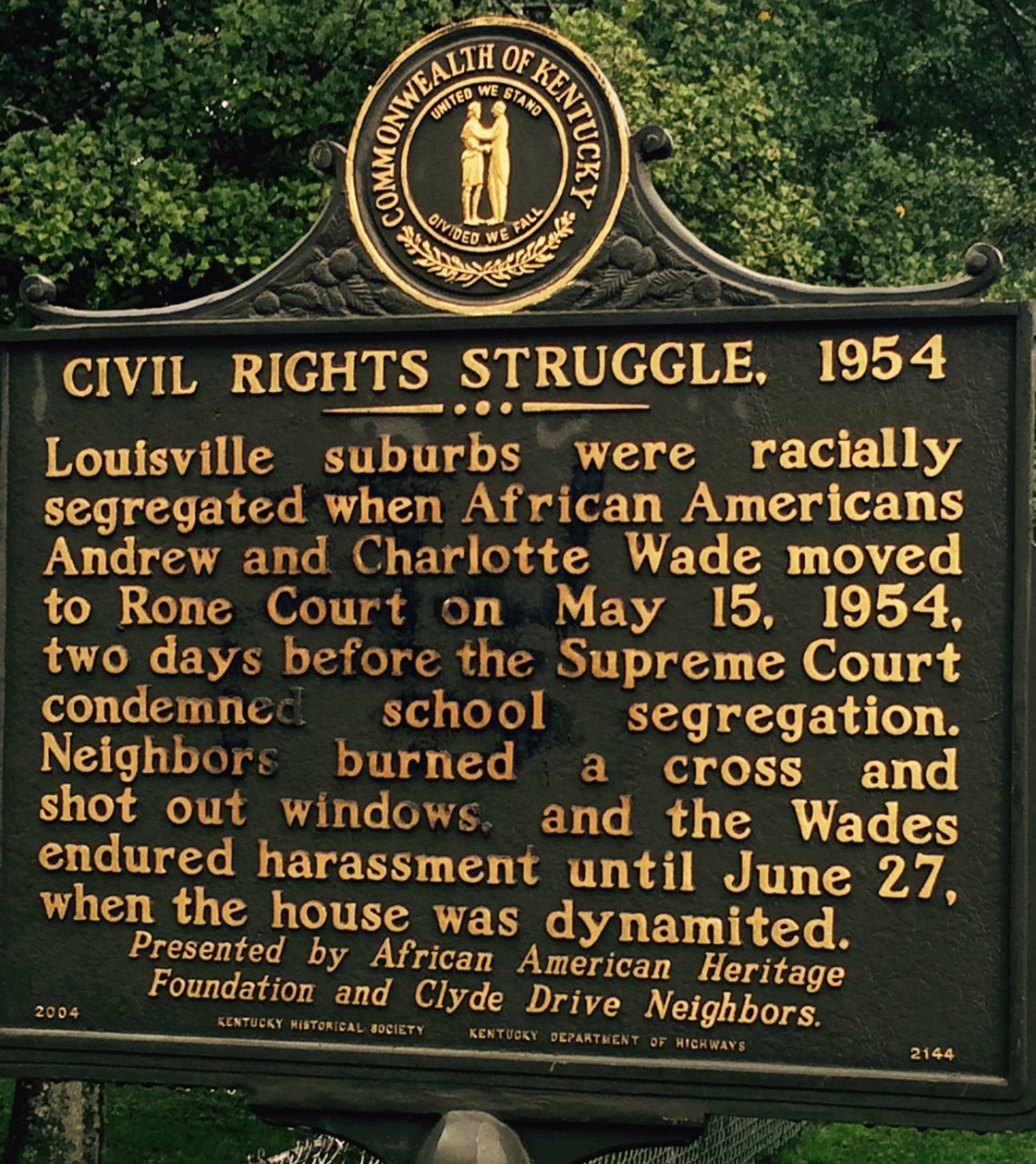

This neighborhood in the Louisville community of Shively seems a most unlikely place for cross-burnings, gunfire and a dynamite attack, but that’s exactly what happened along this street over the course of several weeks in 1954.

The hostility began when an African-American family, Andrew Wade, his pregnant wife Charlotte and their 2-year-old daughter Rosemary moved into their new home at 4010 Rone Court.

Andrew Wade was an electrician who wanted to move his family to the suburbs but was turned down by a succession of white realtors who refused to cross the illegal but still highly observed line of segregation.

In an interview from the 1980s, featured in the documentary "Anne Braden: Southern Patriot," Wade recalls a piece of advice he received from one realtor:

"He said Wade, let’s be realistic. If you see a house you like the house, regardless of where it is, get a white person if necessary if it’s in a white neighborhood, to buy the house for you and transfer it to you. It’s that simple."

So, that’s what he did. Wade enlisted the help of acquaintances Carl and Anne Braden, left-wing activists who had been vocal in their opposition to Louisville’s housing segregation laws.

The transaction was completed but trouble began as soon as the Wades moved in, as Anne Braden recalls in the documentary:

"That night, they heard gunshots, and somebody was firing at the house, and Andrew says he told his wife to get down and so forth, but it didn’t hit anybody. And they looked out and there was a cross burning in the field next to them."

There would more trouble in the days to come: a stone bearing a racial epithet hurled into a window, the local dairy refused to deliver milk, the Wades’ newspaper subscription was canceled because the carrier wouldn’t deliver it.

"It is one of the most integrated, multiracial, multicultural neighborhoods in Louisville today."

Cate Fosl

Police were stationed nearby for protection, but the Wades and their white allies didn’t trust them, so they formed a committee whose members would take turns staying in the house.

One of the guards was Lewis Lubka, now 88 and the last surviving activist.

"I was in the back kitchen with a gun. And when we were shot at, we shot back. I was working days and helping guard the house at nights," Lubka said.

Several weeks went by and tensions seemed to ease a bit. But just after midnight on June 27, 1954, Lubka said "we was coming in and a bomb went off under the house."

The home was blown up with dynamite. The explosives were placed under the room of 2-year-old Rosemary Wade. No one was in the house at the time.

Cate Fosl is a biographer of Anne Braden and heads the Braden Institute for Social Justice Research at the University of Louisville. She says it was no secret who was responsible for this and other attacks.

"No indictments were returned against any of the neighbors, even though they had admitted to burning a cross and being hostile to the idea. But all of the indictments were against the whites who supported the Wades in this quest for a house," Fosl said.

Anne and Carl Braden and the five other whites were charged with sedition, accused of hatching a communist plot to buy the home, blow it up, touch off a race war and overthrow the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

Today, it sounds outrageous. But in an interview from the collections of the Kentucky Historical Society, Anne Braden provided some context — this happened at the confluence of McCarthyism and Brown vs. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that outlawed school segregation:

"And I always felt that the Wades and us became lightning rods. They couldn’t get at the Supreme Court but they could get at us."

Carl Braden was convicted and spent eight months in prison. The following year, a ruling came down from the U.S. Supreme Court in a Pennsylvania case that said, in essence, sedition is a federal crime, not a state offense. Carl Braden’s state conviction was later reversed and the charges against the other defendants were dropped.

Branded as communist troublemakers, all the defendants had trouble finding work in the following years. Carl Braden died in 1975. Anne Braden continued her work opposing housing and school segregation.

The Wade family attempted to repair their home, but amid continuing hostility, sold the house at a loss and moved back to the inner city, where Charlotte Wade still lives. She no longer speaks publicly about the case. Andrew Wade died in 2005.

Anne Braden, who died in 2006, told the Kentucky Historical Society that she had no regrets about helping the Wades buy their dream home.

"It would have been unthinkable to us to say no, because this is something we believe in. Either you live by what you believe in or you don’t, that’s all," she said.

Braden biographer Cate Fosl says the Bradens and the Wades would be proud of how the once-troubled Shively neighborhood has changed.

"It is one of the most integrated, multiracial, multicultural neighborhoods in Louisville today," Fosl said.

It’s also the home of 31-year-old postal worker Steve Ebbs, his wife and two young daughters. He’s the great-nephew of Andrew and Charlotte Wade, and lives down the street from 4010 Rone Court, now called Clyde Drive.

Ebbs has been the family’s spokesman during the anniversary commemorations.

"It’s something that I really take pride in and I’ve made sure that my children understand the significance of the fact that there’s a monument here and it is our blood relatives that went through what they did to receive something like this. So I make sure that I definitely give it the respect that it’s due."

Reporter

- Rick Howlett, editor, reporter and host for WFPL, Louisville Public Media. He tweets @rickhowlett.

This segment aired on December 1, 2014.