Advertisement

10 Years Later: Hurricane Katrina Evacuees In Houston

ResumeAfter Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, many people relocated to other cities and towns, including Houston, Texas. But rebuilding community and recovering from the upheaval from the disaster takes time. The experiences of many evacuees were documented in an oral history project convened by a University of Houston professor. Reporter Syeda Hasan of Here & Now contributing station Houston Public Media spoke with two evacuees about what it took to call Houston home.

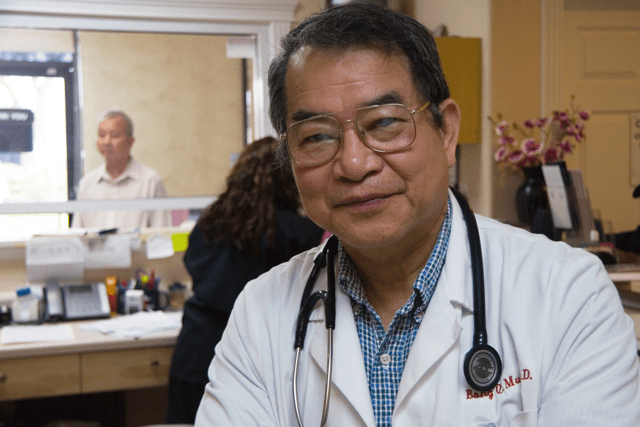

Just a few minutes after opening, the waiting room at Dr. Bong Mui’s clinic is brimming with patients. His family practice is located next to a Hong Kong Food Market in North Houston. Over the past 10 years, Dr. Mui has gained many loyal patients, but it wasn’t always this way. Mui struggled to rebuild his practice after coming to Houston as an evacuee from Hurricane Katrina.

“I lost everything. Two offices, our hospital, and my wife at the time had a day spa, and it’s completely lost,” he explains.

When the storm hit, Mui was chief of staff at a small New Orleans hospital. While the rest of the city evacuated, he and two other doctors stayed behind to care for patients. They were eventually rescued, and Mui became one of the estimated 15,000 Vietnamese evacuees to relocate to Houston. Rather than taking refuge in shelters like the Astrodome, many moved in with friends or family. The community shared a sense of solidarity having lived through the perils of the Vietnam War. So Dr. Mui says he took Katrina in stride.

“Going through so many difficult times, I just feel like, OK, we could survive and we could revive ourselves, in a way."

"Going through so many difficult times, I just feel like, OK, we could survive and we could revive ourselves, in a way."

Dr. Bong Mui

Mui says he felt at home among Houston’s large Vietnamese population. But the experience of Katrina was still weighing on him, and sharing that story was an important part of his healing process. So Mui got involved in an oral history project that captured the experiences of hundreds of Katrina evacuees.

Dr. Mui says he lived in New Orleans longer than he lived in Vietnam, and he felt just as connected to the city. He talked with other evacuees, and says many felt the same way.

“I love home, I love New Orleans, and I love home Houston too," says Lumar LeBlanc, a drummer in a brass band called the Soul Rebels. A New Orleans native who grew up in the 8th Ward, LeBlanc also took part in the interview project.

LeBlanc loved the jazz and funk music he’d hear playing in the neighborhood, and took up drumming as a career. But after Katrina, LeBlanc’s band didn’t play for months. Many of their instruments were destroyed in the storm. He remembers watching news reports as flood waters engulfed New Orleans.

"We were like, 'This can’t be happening. Is this true? Is this our city?' That’s when the tears started to flow. That’s when all of the insecurities set in. 'I wonder if my home’s ruined.'"

LeBlanc moved his family of six into a two-bedroom apartment in this bustling southwest Houston neighborhood. It was a far cry from life in New Orleans, a city that takes up about 170 square miles. Houston is more than 50 times that.

LeBlanc missed being able to get around on foot, chatting up old friends and strangers on the street. People were just more open in New Orleans, he says. But when he played his first show in Houston, he started to regain that sense of community.

“God, I just couldn’t believe how warmhearted the people were," he recalls. "The people were like, ‘man, here’s my number if you need anything.’”

LeBlanc says he’s thankful for the outpouring of support. But he also knows that there were mixed feelings as Houston was flooded with thousands of displaced people. Some residents expressed concerns that evacuees were bringing crime to their neighborhoods. LeBlanc calls those beliefs “phobias.”

By taking part in the interview, he wanted to share his story in his own words. And that was the whole idea behind the project.

"I just couldn’t believe how warmhearted the people were. The people were like, 'man, here’s my number if you need anything.'"

Lumar LuBlanc

“What I found really stunningly and movingly consistent, was that no matter how different the experiences were of those two different individuals, the interviewer listened with respect to what the interviewee had to say," says Carl Lindahl, a University of Houston professor who organized the oral history project.

He and his team paired evacuees up and had them interview each other. Some conversations lasted for hours. Lindahl says rather than feeling cynical about the disaster, many survivors seemed to empathize with each other.

“A number of people who I think normally wouldn’t have given each other the time of day spent a long time listening to each other,” Lindahl says.

Lumar LeBlanc says he felt that compassion from other evacuees and from Houston residents. The experience inspired one of his songs, called “Why Can’t We Be One People.”

Today, LeBlanc is settled into a suburban Houston home. He still plays gigs in New Orleans almost every weekend. Ten years after Katrina, LaBlanc says he feels longtime Houston residents and people who came from New Orleans are a little closer to coming together as one.

Reporter

- Syeda Hasan, reporter at Houston Pubilc Media. She tweets @SyedaHasan887.

This segment aired on June 24, 2015.