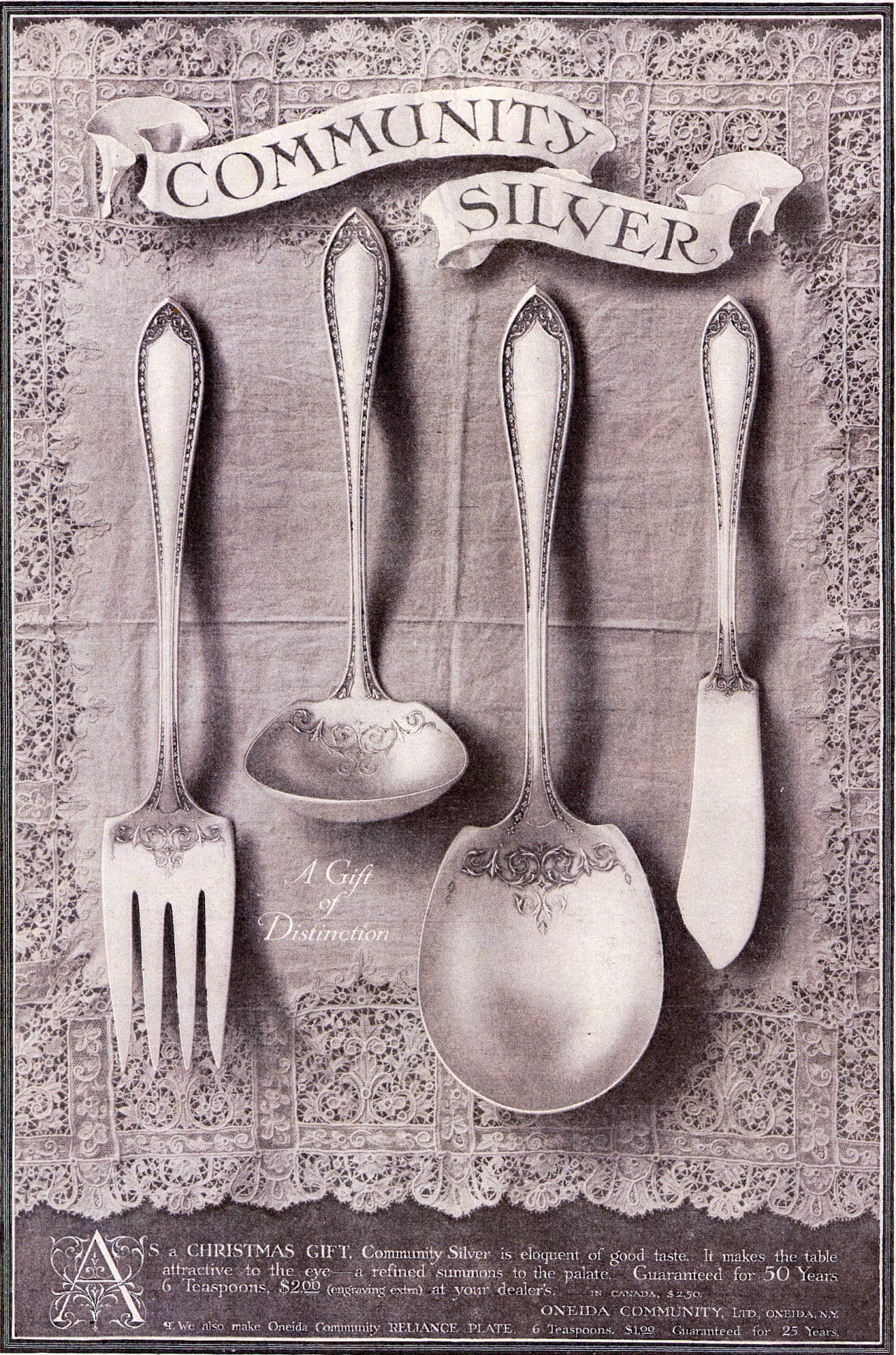

Advertisement

The Rich, Sexy History Of Oneida — Commune And Silverware Maker

Resume

America in the mid-1800s was rife with experiments in communal living. One of the most controversial approaches was in Oneida, NY, where the community's founder, John Humphrey Noyes, proclaimed the practice of free love and breeding for a super race. When that idea disintegrated, Oneida embraced the production of silverware.

Here & Now's Robin Young talks with Ellen Wayland-Smith, a descendant of Noyes, and the author of "Oneida: From Free Love Utopia To Well-Set Table."

Book Excerpt: "Oneida: From Free Love Utopia To The Well-Set Table—An American Story"

By Ellen Wayland-Smith

Tirzah miller liked to have sex. a typical anecdote from the diary of this niece of John Humphrey Noyes and member of his exclu- sive inner circle recounts an impromptu romantic encounter with her on- again, off-again lover James Herrick. One day, while wearing his favorite white dress (“he calls me his little bride in it”), Tirzah and Herrick were caught during a rainstorm in the community business office. “There was a wonderful glow and ache between us,” Tirzah later rhapsodized in her jour- nal. “We seemed all aflame. We hurried to the house, and then he wanted me to come to his room. Ecstasy.”1

Tirzah was by many accounts the most sexually sought-after woman in the community. That she was a “powerful social magnet,” as one commu- nity elder commented of her, there can be no doubt. Tirzah’s diary is lit- tered with bewitched men, broken hearts, and sulking lovers caught in the snares of sticky love. The most glowing testimony to Tirzah’s sexual magne- tism comes from John Humphrey Noyes himself, who saw Tirzah as both a sexual and a political ally within the community. With his unswerving instinct for coining the most vividly awkward sexual metaphors, Noyes once commented to Tirzah that women’s differing degrees of prowess in bed resembled the difference in music produced by “a grand piano and a ten-penny whistle.” Tirzah’s own efforts in the arena of making “social music” he categorized as “sublime.” Coming from a man who saw sexual ecstasy as a path to achieving union with the godhead, this was high praise indeed.2

The fact of Tirzah Miller’s libido being in permanent overdrive was a lucky thing for John

Humphrey Noyes. For, beginning in 1869, he had chosen Tirzah to be the cornerstone of an ambitious new plan he was hatching for the community: a eugenics experiment, whereby the high- est spiritual members would cross-breed to produce a new race of super- Perfectionists. After twenty years of struggling to achieve perfection through the labor-intensive processes of Mutual Criticism and self-discipline, per- fection would now be “fixed in the blood,” blueprinted at the cellular level.3

Noyes’s bold experiment, the first (if not the only) practical eugenics trial in America, was different, it should be said, from the garden-variety eugenics societies that would spring up in the early decades of the twenti- eth century in England and the United States. For groups like the British Eugenics Society and, in the United States, Charles Davenport’s Ameri- can Breeders Association, the goal was always the rather pedestrian one of preserving Anglo stock from contamination by the lower classes and races. Under the misleadingly mild motto that “Eugenics Is the Self-Direction of Human Evolution,” the International Eugenics Conferences held in New York in 1921 and 1932 favored immigration restriction and forced sterilization to weed out genetic undesirables. The English biologist Julian Huxley, for whom Noyes was a great inspiration, held slightly more en- lightened views, and in a 1936 lecture he championed eugenics as a way to prepare humanity for the advent of a pacifist-socialist world state in which the capitalist vices of selfishness and greed would be bred out of human DNA. But for sheer chutzpah, it must be said, Noyes outdid any of his successors in eugenics: he believed humans might be bred for nothing less than immortality. But, as with all creatures that fly too close to the sun, those who participated in Noyes’s experiment were destined to singe their wings.

Excerpted from ONEIDA by Ellen Wayland-Smith, published by Picador. Copyright © 2016 by Ellen Wayland-Smith. All rights reserved.

Guest

This segment aired on May 20, 2016.