Advertisement

How One Man Went From 'Truffle Boy' To New York Food Entrepreneur

Resume

Ian Purkayastha has loved truffles ever since he first tasted them as a teenager. At 15 years old, he was selling them to restaurants in his hometown of Fayetteville, Arkansas, while still attending high school.

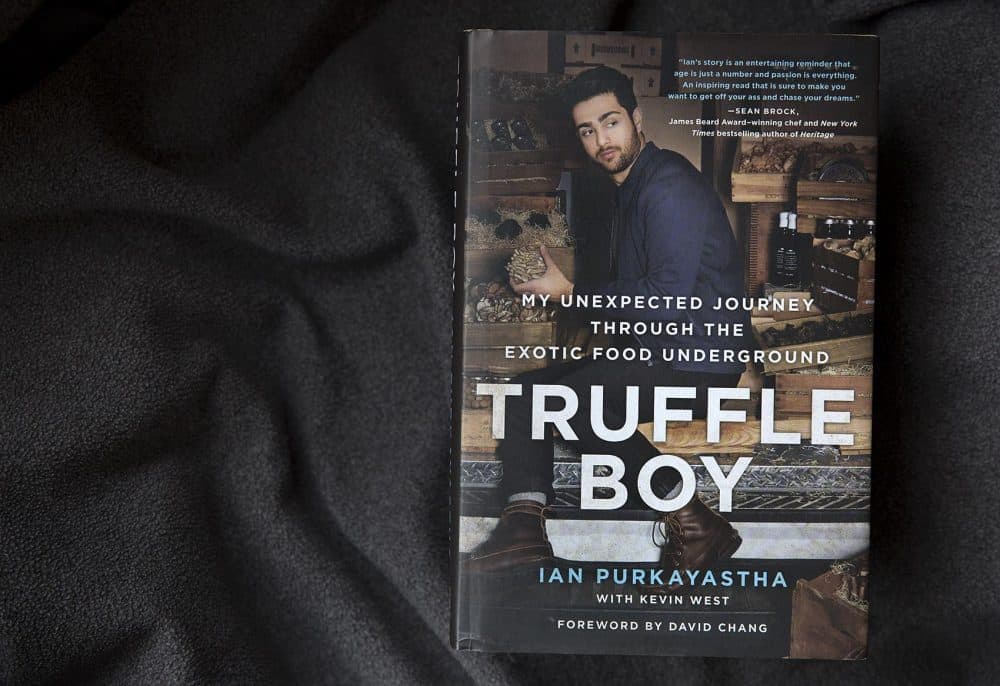

Purkayastha (@IanPurkayastha) has since parlayed that love into Regalis, a specialty foods business. He's also written a memoir, "Truffle Boy: My Unexpected Journey Through the Exotic Food Underground," and joins Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson to talk about his story.

Interview Highlights

On what sparked his interest in truffles growing up in Arkansas

“Well, my family actually relocated from Houston, Texas, to rural Arkansas when I was 15. And the move to Arkansas was really to pursue a simpler lifestyle. My uncle and his family were living in Arkansas, and I started spending a lot of time with my uncle, who was an avid outdoorsman. And he showed me how to mushroom forage. So the first few mushrooms he showed me how to forage for were morels and chanterelles and black trumpets. And I had always loved cooking and eating well, and so I kind of became obsessed with all things mushroom-related. And I knew the truffles were regarded as the ‘king of all of mushrooms.’ And so, on a visiting trip to Houston, I was fortunate enough to go to dinner with some of our old, affluent friends from Houston, and they told me that I could order anything on the menu. And I saw this black truffle ravioli dish with the foie gras sauce. And so I ordered it, and from the very moment I tasted it, it was this amazing, unusual, earthy flavor, and I just became totally obsessed. And so when I returned Arkansas, I begged my parents to give in to buy me a truffle or two. And their immediate reaction was, ‘Of course not,’ because Fayetteville was kind of our reset at all things lavish and fancy, and so I decided to pull together my savings from several Christmases, in hopes of buying my first shipment of truffles.”

"I would say if someone is wanting to try an ingredient that literally smells like nothing else you've ever had, then the truffle is the ingredient for them."

Ian Purkayastha

On how he first started buying and selling truffles

“So the minimum was actually a kilo of truffles, and so my original intention was not to sell them, but to just buy a few truffles to eat, you know, for personal consumption. And so I found this French company in France that was willing to send me a kilo of truffle, and when they arrived I realized there's actually quite a lot of truffles here, and that's when I decided, why not try to sell a portion of these to some local restaurants? So I cold-called the three best restaurants in town, and my dad drove me and I stopped at Target along the way, picking up a little kitchen scale, and I basically just pretended like I was making a delivery, and showed up to the chefs and said, ‘Oh, I have these truffles from France, and would you like to buy a few?’

“...It’s a simpler process than you might think. I just showed up and said, you know, ‘I've got these truffles, do you care to take a look?’ And I don't know if it was the novelty of this young, buck-toothed kid walking and with truffles, or the quality of the truffles themselves that completed the sale, but I had fun with it and I turned the profit. And I just kept reinvesting in larger and larger orders, and my parents would take turns driving me to local, larger cities, and I would hop out and cold call and cold call. I established this little company in Arkansas, and I turned my parents’ garage into a shipping center, and I would go to the airport after school several days a week to go pick up the truffles that had arrived, and I would make sales in between classes.”

On how he learned to discern good truffles from bad truffles

“Everything I've learned in these nine years has been self taught — that's not to say I've had a lot of help along the way in terms of meeting so many amazing people in this industry. But I have always loved cooking, and I grew up cooking with my grandfather and my mother, and entertaining and cooking for people was always such of strong importance. And so I’ve just applied that same passion for food to truffles.”

On whether the truffle industry is “shady”

“It is. It totally is shady, and I think part of the success that I've been so lucky to have with my company and my reputation is that I'm very transparent about all the ingredients that we sell. What I'm trying to do with ‘Truffle Boy’ is to also demystify these once... very, underground, lux ingredients that had these snobby reputations, and be as educated as possible, and also try to just make these ingredients a little bit more approachable for a younger generation."

On advice for people who have never had a truffle

“I would say if someone is wanting to try an ingredient that literally smells like nothing else you've ever had, then the truffle is the ingredient for them. Truffles have been, you know, lustful and highly regarded for centuries for having this intoxicating aroma and flavor. So I would definitely encourage interested, adventuresome eaters to seek out truffles.”

Book Excerpt: 'Truffle Boy'

By Ian Purkayastha

Twelve miles out from the Empire State Building, as you rattle across the overpass from the New Jersey Turnpike toward Newark Airport, you can look left and see a double-height warehouse with letters on its facade that spell out united cargo. The u fell off once, and every time I saw nited cargo, I thought about the truth of my industry, the food business. It’s benighted: dark, shadowy, shady.

That warehouse is Newark’s cargo terminal, where night flights from around the world bring goods to the Tri-state area, home to twenty million Americans with a collective economic output greater than that of all but a dozen countries. The Newark cargo terminal is a global rendezvous point for the flat-world economy, a depot for valuable commodities, a clearinghouse for perishable freight that wouldn’t withstand slower passage upon the high seas. Inside I’ve seen pallets of iPhones from China, long-stem Ecuadorian roses, Ferraris, caged live birds, whole king salmon from Alaska’s Copper River, and human corpses that arrive in giant Styrofoam coolers and are met by hearse-driving funeral directors.

I know Newark’s cargo terminal well because New York is a hungry city, and my job is to supply chefs with the exotic delicacies they use to seduce their customers. Black and white truffles, caviar, Japanese Wagyu beef, Spanish pata negra from abroad. Golden chanterelles, matsutake, and porcini foraged from the Pacific Northwest. Ramps, pawpaws, and wild ginseng harvested from the ferny hollows of the Appalachian Mountains. The kind of products I sell fly into Newark like first-class passengers, the 1 percent of the food world, and within hours they are being prepared in the fin- est restaurants in New York City—the Michelin-starred, New York Times–celebrated, Best Restaurants in the World list–topping show- places run by celebrity chefs like Daniel Boulud, David Chang, and Thomas Keller.

What I sell are known in the industry as specialty foods. They represent a niche within the already small niche of grade-A, hand-selected, thoughtfully curated local/seasonal/organic/artisanal food you find on ambitious menus. The specialty foods game is fierce because the stakes are high, and New York is where you can make it big if everything comes together just right—or lose everything if it doesn’t.

At the height of white truffle season, which runs from October to New Year’s Day, I can sell fifty pounds a week. In volume, that’s nothing compared to the fifty pounds of potatoes a restaurant might use for a single meal service. But fifty pounds of truffles amounts to $100,000 wholesale. Even jaded chefs perk up when I walk in with a basket of truffles. I’m horrible for a restaurant’s food costs, but chefs will pay anything for my product. Nothing in the kitchen, with the possible exception of cocaine or twenty-year-old Pappy Van Winkle, makes a chef hornier.

Other companies will say that they have the best truffles, or caviar, or mushrooms, or olive oil, or whatever. What you need to understand is that the specialty foods market is rife with fraud. Adulteration is rampant. Counterfeiting is commonplace. Things like substituting worthless Chinese truffles indistinguishable in appearance from true European black truffles but lacking all flavor. Caviar treated with borax, which gives the beads extra pop but can melt your liver. Foie gras dyed yellow because that’s how chefs think it should look. “Italian” olive oil that is actually produced by agribusiness giants in Turkey or Greece, shipped across the Adriatic in tanker ships, funneled into pretty glass bottles, and labeled extra-virgin as if it came from some ancient Tuscan grove. And it’s not just a luxury-food issue. Even the most basic ingredients in your pantry are likely adulterated. Preground black pepper is doped with ground olive pits. Salt is cut with talc and other fillers. Eater beware: The food industry is like the Wild West. My goal from the start has been to change that—still is.

But that’s to come. For now my point is simply that the belly of New York rumbles mightily, and the city devours every morsel that reaches its greedy maw. Nothing is too expensive or too exotic, and my job is to scout the world for the most delicious foods known to man.

It’s also worth knowing that the first time I went to Nited Cargo to pick up a shipment of truffles from Italy, I was seventeen years old. That’s when I moved to New York with a dream. Three years earlier I had found my calling at my grandparents’ cabin in the Ozark Mountains of northwest Arkansas. That April day I walked out the back door with my uncle Jared, and he taught me how to forage for morels. The next year I learned about truffles.

Truffles, if you don’t know about them, are the ultimate mush- rooms. They come out of the ground damp and lumpy, looking like clods of dirt. The French call them “diamonds of the kitchen,” because they are rare and because beneath their drab exterior they contain an inner mystery, a unique aroma that no one can fully describe. It encompasses fragrances of mushrooms and Parmesan cheese, garlic and chlorophyll, cured meats and herbs, the smells of the soil and the seasons, of intimacy and rebirth, the complex and elusive scent of human desire.

Using savings pooled from three Christmases, I bought a kilo of truffles off the French version of eBay and sold to chefs in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. Overnight, I became a teenaged truffle dealer.

When I graduated from high school, I ditched college and moved to New York to sell truffles. I had convinced my parents to at least let me try. My dad had moved to America from India and become an entrepreneur, so he understood risk, and my mom is Texas tough. They agreed to my plan, which most parents would have shut down as a lunatic pipe dream. When I left home in Arkansas with $5,000 in my pocket, all I knew about the New York restaurant scene was what I had read in Frank Bruni’s reviews for the New York Times. I did at least have a job lined up as the North American sales director for the Italian truffle importer Tartufi Rossini.

Rossini was based in a small town outside of Perugia, in the truffle-producing region of Umbria. Between my junior and senior years of high school, I had met Ubaldo Rossini, and we started working together. That winter I sold $233,000 worth of truffles to restaurants in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. My cash margin was almost zero because we discounted prices to move volume in my backwater market, but money mattered less to me than the truffles themselves. Ubaldo let me take my profit in black diamonds. I had truffles by the pound: to hold, to smell, to fold into ravioli bedded in foie gras sauce. Ubaldo, who was twenty-seven when we met, became my first friend in the industry. He was the guy I wanted to be back then. When he offered me the chance to move to New York as Rossini’s first employee, I jumped at it, and in July 2010, my mother flew with me from Arkansas to get me settled into my new home.

Except that my life in “New York” was actually based in New Jersey and would be for the next two years. I couldn’t afford Manhattan, even with Ubaldo chipping in one-third of the rent, and instead I settled for an attic apartment on Shippen Street in Weehawken, across the Hudson from Midtown. From the end of Ship- pen Street I could see where I wanted to be: somewhere in the view that stretched from Columbus Circle to Wall Street, which at dusk looked like a Woody Allen love letter to the Big Apple. The reality was that Shippen Street dead-ended above the Lincoln Tunnel, which farted out cars and fumes twenty-four hours a day. The restaurant people I eventually got to know lived in Brooklyn or the Lower East Side or in Hell’s Kitchen, the one stretch of Manhattan that hadn’t been gentrified by tattooed hipsters with financial sup- port from home. Weehawken’s only benefit was being closer to Tartufi Rossini’s office in Newark, a city rightly known as the shithole of America.

My block looked like a blue-collar neighborhood in Pennsylvania or Ohio, and the house where I lived must have been nice seventy-five years ago. It had two full stories and an attic with a dormer window, a front porch framed by columns, and a small yard two steps up from the sidewalk. Most of the houses on the block had been split up for rentals since then, and third-hand cars lined the street. An old SUV sagged on its busted suspension, and a dented sedan’s sun visor hung down like a stroke patient’s eyelid.

My house’s pale green siding had faded to gray, and lichens crusted the foundation. Green slime spread from under the porch and filled the cracks in the concrete steps. The house trim had flaked down to bare wood, and as you opened the front door, the brass knob rattled in its mechanism. Inside the vestibule, it smelled like Roberto, my landlord—cigarettes and mothballs.

My apartment was two flights up. The first floor was rented to a couple I almost never saw, and from there a small staircase led to the attic. Years of renters had scuffed the risers and worn the nonslip strips off the treads. The attic walls slanted under the roof gables, and I could only raise my hands over my head in the middle of the room. There were two bedrooms behind hollow-core doors, one facing the street and the other overlooking the backyard. The kitchen had a smelly fridge, a cheap stove, and yard-sale cooking utensils. My bathroom was so small you could touch all four walls while standing at the sink, and the rotten trim around the shower looked like it might give up any day. I slept in the front bedroom under the dormer, and from the window, I could see the neighbor’s yard across the street. Years ago he had decorated it with a cement statue of a whitetail buck that was now missing most of its paint and all of its right antler.

On Monday morning, after my mom flew back to Arkansas, I took a bus to Newark Airport to collect my first shipment of truffles. They were summer truffles, Tuber aestivum, a wild European species that is harvested from May to August. T. aestivum has a chocolate-brown peridium, or skin, covered with pyramid-shaped warty scales. The interior, or gleba, is also dark brown, but criss-crossed with a network of white veins. Summer truffles have a relatively mild aroma compared to the more famous European winter white truffle, Tuber magnatum, and the European winter black truffle, Tuber melanosporum, but their fragrance has a unique hazelnut note. Chefs are happy to get them when the more glamorous cousins are not in season. Ubaldo had sent me forty pounds from Italy, and from the airport I caught another bus back to the office, where I sorted them by size and aroma and left them in the refrigerator overnight.

The next day I woke up early to get ready for my first day of sales, which unfortunately coincided with a heat wave. I caught the bus to my office and filled a rolling ice chest with $10,000 worth of truffles along with ice packs, a digital scale, and a new invoice book—basically a drug dealer’s setup but with better record keeping. I caught another bus to Port Authority in Midtown, and transferred to the Eighth Avenue Line to Columbus Circle. My plan for the day was to make cold calls to seven restaurants I’d nabbed from Frank Bruni’s reviews. The first was Per Se.

Excerpted from the book TRUFFLE BOY by Ian Purkayastha. Copyright © 2017 by Ian Purkayastha. Republished with permission of Hachette Books.

This article was originally published on February 16, 2017.

This segment aired on February 20, 2017.