Advertisement

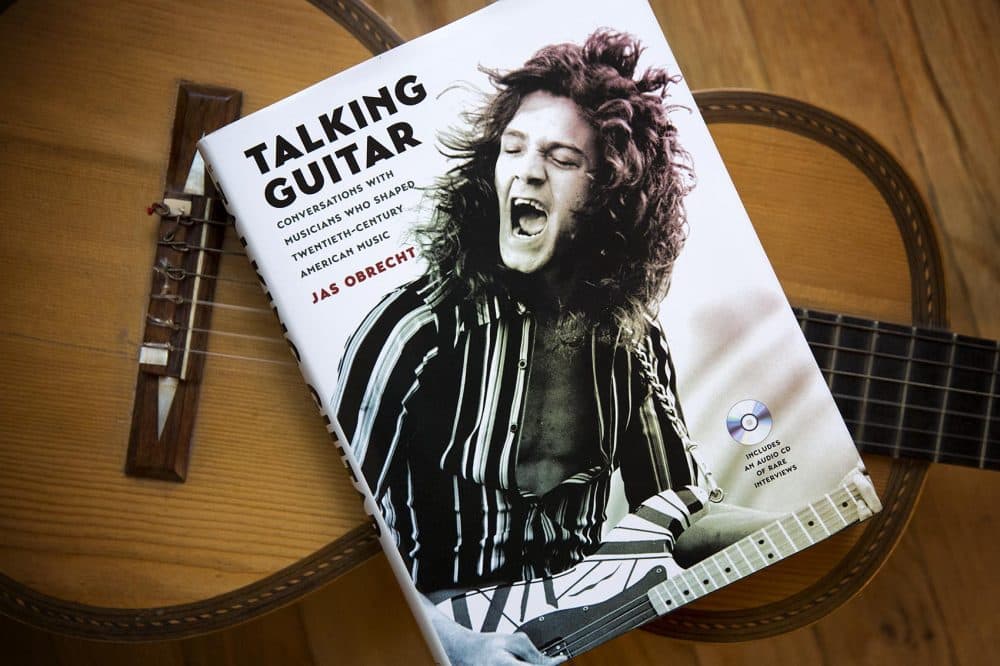

'Talking Guitar' Offers Front-Row Seat To Conversations With Rock Music Giants

Resume

From Nick Lucas in the 1920s to modern-day artists like Eric Johnson and Eddie Van Halen, a new book collects conversations with some of the leading guitar players in American music history.

Here & Now's Robin Young listens to some of them, and speaks with Jas Obrecht, author of "Talking Guitar: Conversations With Musicians Who Shaped Twentieth-Century American Music" and former editor of Guitar Player magazine.

Nick Lucas On "The Tonight Show" In 1969

Jimi Hendrix, "Somewhere"

Eddie Van Halen, "Eruption"

Eric Johnson, "East Wes"

Joe Satriani, "Flying in a Blue Dream"

Book Excerpt: 'Talking Guitar'

By Jas Obrecht

Setting the Stage

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the guitar was mainly used as a “parlor” instrument suitable for small-group entertainment and serenading. The instrument was typically found in saloons, pool halls, grange lodges, barbershops, and at church services. Even then, the guitar’s popularity extended across social, class, and gender boundaries. While guitars were readily available through music stores and mail-order catalogs, few recordings of guitar music were available during the first decade of the 1900s, when most players learned from teachers and sheet music.

In rural areas, many young players started out on homemade stringed instruments. The most common of these, the diddley bow, probably originated in Africa. A diddley bow was typically fashioned by attaching broom or baling wire to nails in a wall or doorframe and using bottles or rocks as bridges. One hand plucked the wire, while the other fretted or glissed the string with a bottle. Many outstanding blues guitarists—Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Buddy Guy, and Johnny Winter among them—began this way. Others fashioned primitive guitars by attaching a tin can or cigar box to a rough-hewn neck. Those who could save enough money ordered guitars by mail-order catalog. These guitars, in turn, may offer a clue about how European-influenced parlor music came to exert an influence on the development of American blues, folk, jazz, and country music.

During the latter 1800s, the Lyon & Healy company in Chicago pioneered the mass production of acoustic guitars. By the turn of the century, their many models were sold under various names in catalogs issued by companies such as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward. Many of these catalog-bought guitars arrived with a tutorial pamphlet featuring tuning instructions and music for rudimentary instrumentals. Two of the most common of these instructive instrumentals, “Spanish Fandango” and “The Siege of Sebastopol,” predated the Civil War. The music for “Spanish Fandango” required that the guitar’s strings be tuned to an open-G chord (the strings tuned DGDGBD, from low to high), while “The Siege of Sebastopol” was in open D (DADF#AD). “Spanish Fandango” in particular served as a starting point for countless rural players. Its harmonic content, voice-leading chords, and fingerpicking pattern echoed in the repertoires of old-time blues, folk, and country musicians such as Bo Carter, Son House, Furry Lewis, Frank Hutchison, Sam McGee, John Dilleshaw, Mance Lipscomb, and Elizabeth Cotten. To this day, the word “Spanish” is sometimes used to describe open-G tuning, while “Sebastopol” refers to open D.

John Renbourn, the esteemed British fingerstyle guitarist and an expert on the origins of American guitar music, developed a theory of how these instructional booklets contributed to the creation of the blues in particular: “If you can imagine a field hand sitting down after work and trying to fit an arhoolie [field song] across the basic chords of ‘Spanish Fandango,’ then you would be close to the moment of transformation, in my opinion. In the early recorded blues of Charley Patton and his school, the harmonic language, right down to specific chord shapes but with bluesy modification usually of one finger only, is straight from parlor music. The same is true for early blues in open D compared to ‘Sebastopol.’ This is fascinating stuff and fairly controversial, but it fills in the missing gap between the steel-string guitar coming into circulation and the highly developed styles that appeared on recordings in the 1920s.” The 1897 Lyon & Healy catalog featured a budget-priced line of steel-string and gut-string guitars. In its 1902 catalog, the Gibson company listed guitars that could be strung with steel or gut strings.

Still, during the first decades of the new century, the banjo was far more popular than the guitar. Since the Civil War, the banjo had been the instrument of choice for solo performers, blackface minstrel troupes, and string bands. With its bright, penetrating sound and lack of sustain, the banjo could hold its own in orchestral settings. The warm, deep resonance of the guitar was better suited for adagios and blues and country songs, and its sustaining notes could be bent or bottlenecked. One fact was inescapable: during the era of the acoustic recording process, when musicians played into recording horns, banjos and mandolins were much easier to record than classical or steel-string guitars. This held true until the mid-1920s, when Western Electric’s innovative new electrical recording process and microphones came into widespread use.

From TALKING GUITAR by Jas Obrecht. Copyright © 2017 by Jas Obrecht. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.

This article was originally published on June 06, 2017.

This segment aired on June 6, 2017.