Advertisement

Is The Period Dead? One BuzzFeed Editor On How The Internet Has Changed Language

Resume

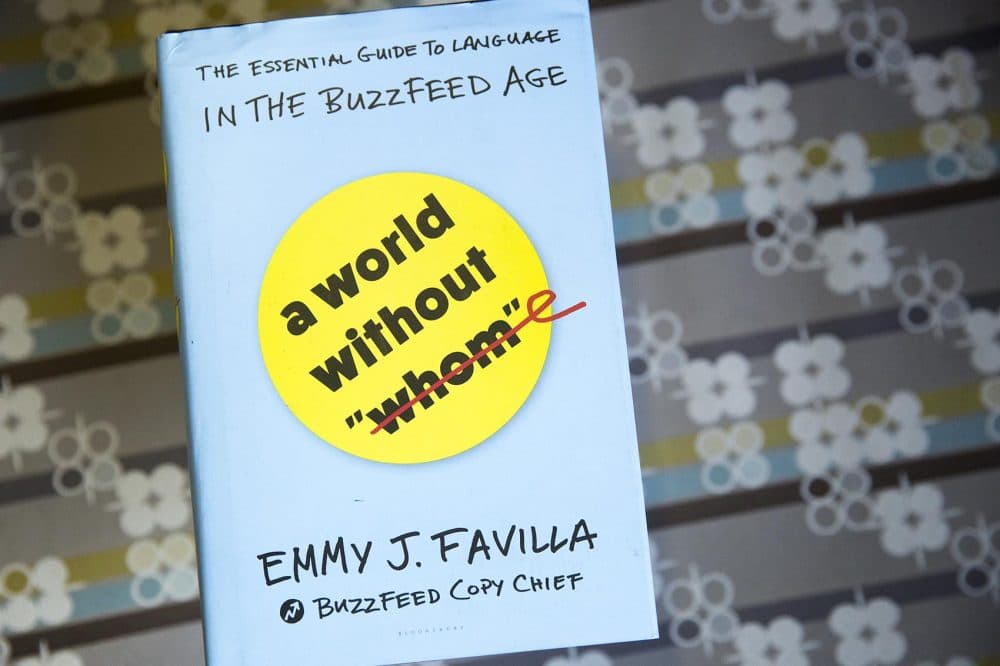

Emmy Favilla, former BuzzFeed global copy chief, has written a guide to language usage and how it's been shaped by social media and the internet.

Favilla (@em_dash3) joins Here & Now's Robin Young to talk about "A World Without 'Whom': The Essential Guide to Language in the BuzzFeed Age."

- Find more great reads on the Here & Now bookshelf

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "A World Without 'Whom' "

Interview Highlights

On grammar rules

"There are rules. I think that the number of hard-and-fast rules is dwindling a bit in this age of omnipresent technology. It's funny to me how everything else in our world evolves — technology, the food we eat, our fashion — but for whatever reason, language is this one thing that people are such sticklers about."

On some common mistakes, and using the right words

"So a 'hoard' is a large collection of something, while a 'horde' is a large group of people, and as a copy editor, I feel like this is one of the top spelling mistakes that I see even from professional journalists and writers. And to be quite honest, sometimes I have to double check, too, because after looking at the words on a screen all day long sometimes I kind of feel like my brain is deteriorating a little bit, and I'm like, 'Oh wait, is that the spelling that means this?' "

"It's so wild that the period, which is the building block of our language punctuation-wise, is sort of a loaded punctuation mark now."

Emmy Favilla

On rethinking language to be more inclusive and sensitive

"One of the big things that we as editors at BuzzFeed, that we come across a lot is talking about people with diseases or disabilities, or dealing with some kind of ailment or condition, and person-first language is really important — person-first language meaning that you put the person before you put their disease or their condition because ultimately we're talking about a human, and we're not talking about a disease that has overtaken a person. And so what that means in practice is that you would say, 'She has cancer,' rather than saying, 'She is a cancer victim.' You also want to avoid phrases that may connote pity and a sense that a person is in this position of powerlessness. 'She is a wheelchair user,' rather than, 'being confined to a wheelchair,' which has that same sort of connotation.

"It's really interesting because we were actually approached by various activists and people who represented organizations for autistic people and they actually asked us to refer to autistic people as that because autism is such an integral part of their identity in the same way that being a deaf person is. You wouldn't really ever find yourself saying 'a person with deafness.' You would say, you know, 'he' or 'she' or 'they are deaf person.' "

On the use of "they" as a singular pronoun

"I am a very big proponent of the singular epicene 'they.' First of all, let's all be honest with ourselves: It's the way that we actually talk. We'll say something like, 'Well if a person is doing X, they should do Y.' And then, of course, you know, it makes room for multiple genders for people who don't identify as male or female, and it just makes for smoother prose when you can avoid the alternative. 'He/she' or '[s]he' or 's/he' or whatever the alternative. That's not only an eyesore but just sort of awkward to say in speech."

On how social media has changed everything

"For one thing it's 'killed the period,' as some might want to argue. I don't think it's killed the period, but it has lessened its importance as end punctuation, because now we can send texts that are one-line messages, we can send direct messages, whether that is over Gchat, or over Facebook Messenger, or as a tweet, or wherever you are sending your one-line message. Now we don't need that end punctuation, and millennials — as they are wont to do, killing everything from napkins, to the diamond industry, to cereal, and whatever else millennials are killing — they have a tendency, I think, that — there've been tons of think pieces already written about this — that the period at the end of a sentence can convey a sort of formality that can come off as aggressive or indicating anger or tension. And it's so wild that the period, which is the building block of our language punctuation-wise, is sort of a loaded punctuation mark now. Also, in tweets, we have a tendency to not use other types of punctuation, like commas, and not use capitalization at the beginning of a sentence, and sometimes it's deliberate, to kind of affect a breezy, aloof kind of tone, especially when it's a kind of weighty statement. There's just a kind of coolness or funniness or whatever the tone you're looking for, maybe, that comes with not punctuating and not correctly capitalizing."

On "whom"

"'Whom' is an antiquated word. We don't use it in everyday speech, in everyday conversation. I see it going the way of 'shan't,' you know, it's just kind of a word that we are organically using less and less. It doesn't really come naturally in speech. It sort of seems pretentious, overly formal. And the worst is when you use 'whom' incorrectly, and I quote Lisa McLendon, who is a very cool professor, I believe, at the University of Kansas, and she presented a session at a conference where she said, 'Always use "who," this way you're not wrong and pretentious.' And that really stuck with me. And it struck a chord and it was a bit of the influence behind the title of the book. It's an example of the way that our language is changing and something we can kind of let go of without feeling bad about it."

Book Excerpt: 'A World Without 'Whom' '

By Emmy J. Favilla

World peace is a noble ideal, but I’d like to step that goal up a notch: A world with peace and without whom is the place I’d like to spend my golden years, basking in the sun, nary a subjunctive mood in sight, figurative literallys and comma splices frolicking about.

This is a book about feelings, mostly—not about rules, because how can anyone in good conscience create blanket rules for something as fluid, as personal, and as alive as language? Something that is used to communicate literally (literally) every thought, every emotion humans are capable of experiencing, via every medium in existence, from speech to print to Twitter to Snapchat? We can’t. Nearly everything about the way words are strung together is open to interpretation, and so boldly declaring a sentence structure “right” or “wrong” is a move that’s often subjective, and we’d be remiss not to acknowledge that most of the guidelines that govern our language are too. Communication is an art, not a science or a machine, and artistic license is especially constructive when the internet is the medium.

And let’s clear the air here, just so you’re aware of the level at which you should realistically set the bar for what you are about to read: I am not an academic. I am not a lexicographer. I am not a grammar historian (a job description I just made up but am pretty confident is a title that actually exists). I did not study linguistics in my collegiate years. I wasn’t even an English major. I am constantly looking up words for fear of using them incorrectly and everyone in my office and my life discovering that I am a fraud. I was a journalism student (and a FASHION journalism graduate student, lol—cut me some slack, I wanted to live in London) with minors in creative writing and Italian studies. I spent my under- graduate years writing reviews of tourist-trap Little Italy bakeries and local Queens venues frequented by high school goths, and my graduate experience consisted almost exclusively of trying to convince snotty PR people to agree to give me a ticket to the standing row of bottom-tier fashion shows. I landed my job at BuzzFeed after admitting during my first-round interview that the only television shows I watched regularly were Teen Mom and all prison reality shows currently on air. This has not changed.

What I am is a person with what I think/hope is a decent grasp of English syntax, an interest in how words are used and how language changes, a fascination with how usage and punctuation (or lack thereof) affects tone, and an unwavering appreciation for an artfully placed em dash. I am a person who happened to stumble into a career in copyediting by way of my journalism degree. It is my accidental livelihood, and I do my best to not fall apart at the seams whenever some- one asks me whether to spell the abbreviated version of until as ’til or til or till (spoiler: I don’t care) or apologizes for a typo or punctuation error in an email to me (what kind of a monster do you think I am???). I have a casual relationship with language, and I know my way pretty well around grammar basics—but I’d never considered myself much of a “language expert” until Kathie Lee and Hoda Kotb invited me on their show in 2014 to do a trivia segment about the origins of everyday phrases and described me as such in that little banner at the bottom of the screen that they put in front of guests. So, I guess it must be true. Let’s drink a giant Wednesday morning glass of wine to that, amirite?

No, I’m not right. I google (that’s right, lowercased as a verb—back me up here, Merriam-Webster) the names of tense categories on a regular basis to trick writers into thinking I know my shit when I present my edits, but I couldn’t identify a future passive progressive verb tense in the wild (i.e., without help from the internet) if my life depended on it. I have to consult the dictionary to figure out whether it’s lain or laid. Every. Damn. Time. I skipped the session on diagramming sentences at the last copy editors conference I attended because I had neither the fortitude nor the brain capacity to last a full hour engaging in said activity.

I would consider myself more of a feelings-about-language expert than a straight-up language expert, mostly because I don’t consider myself a language expert at all. When English isn’t your father’s first language and your mom sounds like she’s spent her entire life auditioning for Fran Drescher’s character in The Nanny: The Musical, that distinction takes a considerable amount of effort to attain—an amount of effort that I’m not sure I’m willing to put in. I’d rather focus my energy on the important stuff, like rescuing street cats or Instagramming the progression of my cactus’s new arms. (It’s grown five of them in less than a year, okay?)

I landed my first real job as a copy editor after a string of editorial internships where my hodgepodge of duties included everything from setting up fashion shoots for indie bands to reviewing books on customer relationship management to visiting showrooms full of lacy decorative pillows. I enrolled in the lone copyediting class that NYU offered during my senior year as an undergraduate journalism student. It was on Friday mornings at 8:30, and Thursday night karaoke at the local bar usually went strong until at least 2 a.m., so I was asleep/hungover/ drunk for most of the lesson and had to let my ~feelings~ (more on the elusory tildes on page 239) guide me through making plenty of editing decisions I didn’t know the hard-and-fast rules for. And either I have really good intuition or my colleagues have been too polite to tell me that my edits have been nothing short of reprehensible over the past decade, but that process has seemed to work pretty well ever since. So well, in fact, that one fateful day in 2012 a slew of senior-level managers at BuzzFeed were duped into thinking I’d be the perfect person to craft what would become the BuzzFeed Style Guide.

Excerpted from A WORLD WITHOUT WHOM by Emmy J. Favilla. Copyright © 2017 by the author and republished with permission of Bloomsbury USA.

This article was originally published on November 29, 2017.

This segment aired on November 29, 2017.