Advertisement

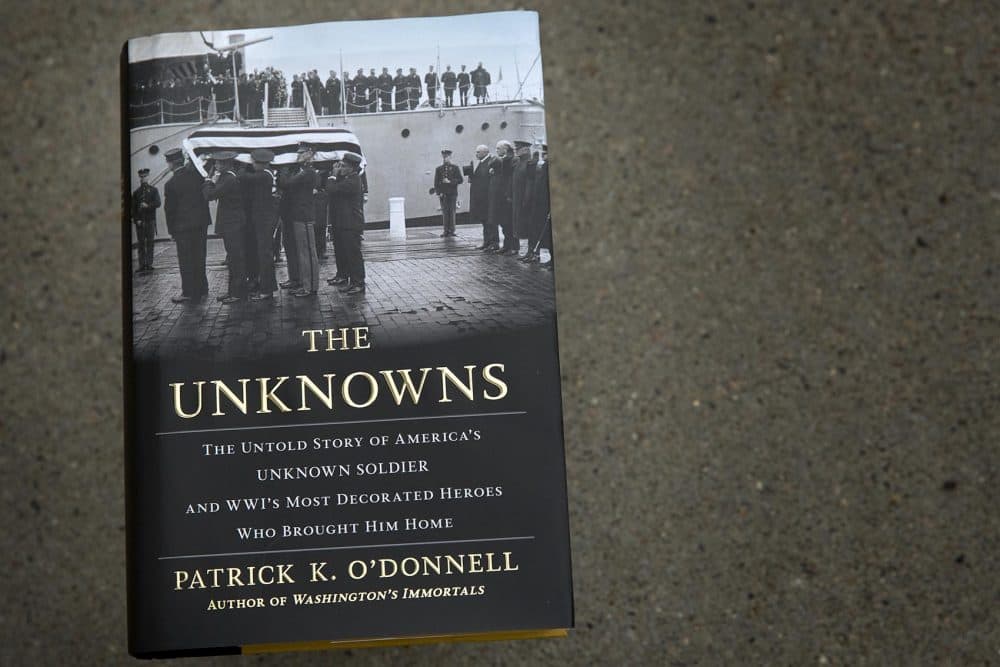

'The Unknowns' Traces Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier's World War I Origins

Resume

After the carnage of World War I, nations that had lost millions of service members were looking for a way to honor those dead. They found a simple concept, with powerful symbolism: The remains of one unidentified soldier, buried with honor, to recognize the service and sacrifice of the many.

An unidentified French soldier was buried under the Arc de Triomphe. Britain interred its unknown in Westminster Abbey.

"Here in the United States, a woman editor of a very famous publication of the time, The Delineator, Marie Maloney, decided to send a letter to basically the brass, that something needs to be done to honor our men," says Patrick O'Donnell, author of "The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America's Unknown Soldier and WWI's Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home."

Here & Now's Alex Ashlock speaks with O'Donnell (@combathistorian) about the history behind the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, and how that first soldier was selected and interred there.

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "The Unknowns"

Interview Highlights

On calls after World War I for the return of an unknown American who had been buried in France to be reburied in the U.S.

"It was in Chalons, France, that four bodies, unknown bodies from four of the cemeteries where the major fighting had taken place in the American Expeditionary Force, were selected. Unknowns were selected — they were very carefully checked to make sure that there was nothing in there that could identify who these men were. And the burial tickets were actually burned after the bodies were selected, and the four bodies were selected and then brought to Chalons, France, and put in the city hall there."

On Sgt. Edward Younger, the American soldier given the honor of selecting which of the four unknowns would come home

"[Younger is] sort of the quintessential doughboy. This is an individual that fought in many of the major battles, right outside of Belleau Wood … for instance, through the war, a place called Blanc Mont, which was kind of like, think of 'The Guns of Navarone,' it's this incredibly fortified position which for years the French could never take. And the 2nd Division, which Edward Younger and the Marines in the 4th Brigade were part of, were able to seize Blanc Mont in an epic struggle.

"But Edward Younger finds himself there that night and he's given the honor to select the unknown soldier, and they hand him a bouquet of flowers that morning, a bouquet of roses, and said, 'Please choose the individual.' And he walked into the room where the sun was starting to come in, and just felt a presence that one of the men in one of the caskets was somebody that had fallen beside him. And he laid the the flowers down on the casket, and that is the unknown soldier that's buried [in Arlington]."

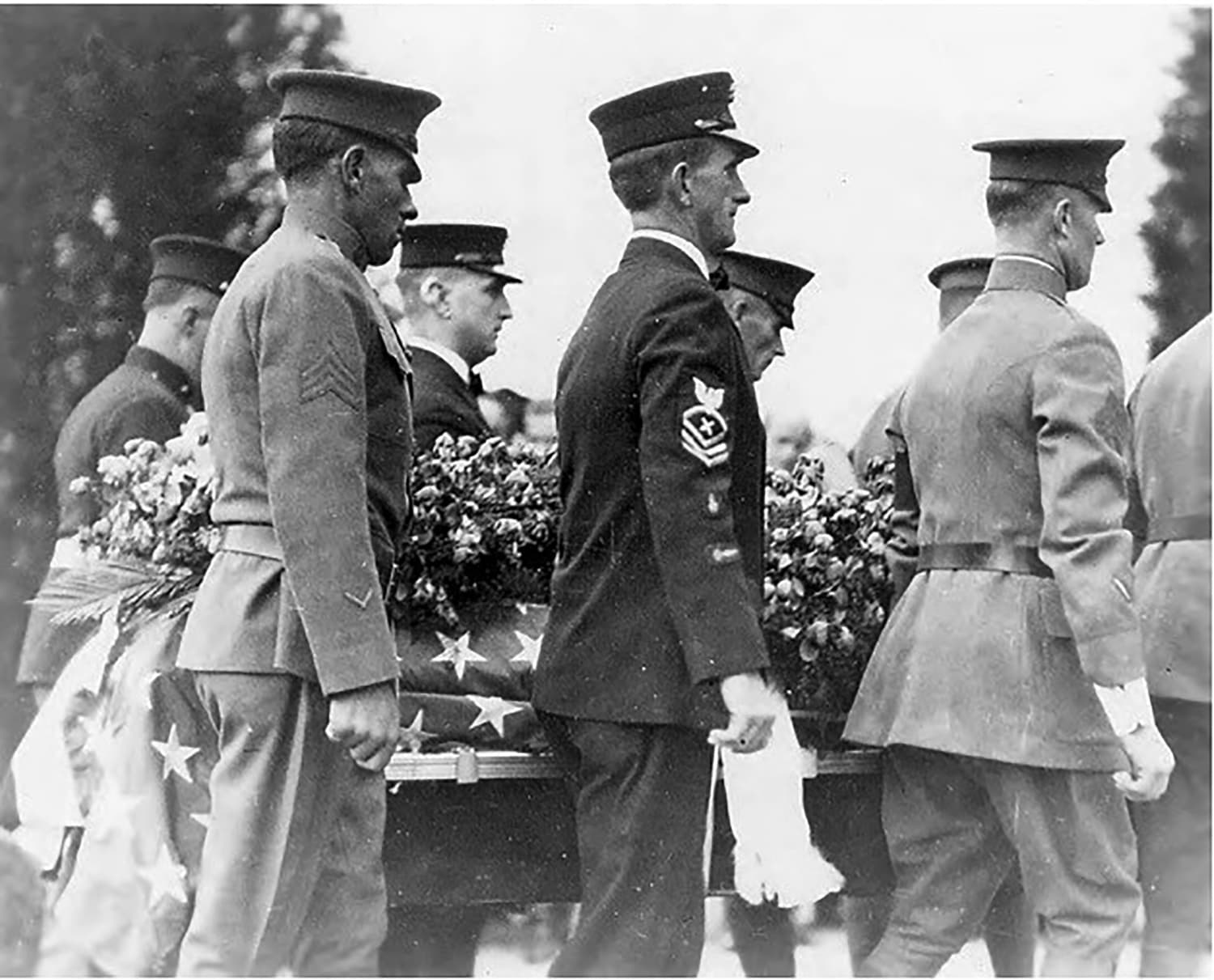

On the unknown soldier's journey to the U.S.

"They bring him back to the United States on board the USS Olympia, which is this storied warship that Adm. [George] Dewey had. The Olympia brings it back, it comes into the Washington Navy Yard and the body bearers — the eight men that are in this book — bring back the remains. It first goes to the Capitol Rotunda, where he lies. There's thousands of Americans that see him. And then the procession comes down from Washington to here in Arlington. Initially, [American Expeditionary Forces Gen. John] Pershing was supposed to be on horseback, but he just wanted to be a regular mourner and walked behind ... with the unknown."

On the unknown soldier's burial ceremony on Nov. 11, 1921

"This was an incredibly important event in 1921, on Nov. 11. This was a chance of healing. Many of the leading organizations, the NAACP, many, many folks were invited to this ceremony. And one of the things that I found really interesting is it was, the last person as the unknown was being placed in the tomb, was Chief Plenty Coups, who was a Crow war chief, was given the honor of placing his war hammer on top of the tomb, and he says several words, even says later on that 'education is your greatest weapon.' But it's part of the healing process of, for many, many years, we fought Native Americans. But this is a chance for them to come together. And one of the body bearers, Cpl. [Thomas] Saunders, was also a Native American, a Comanche, and one of the most decorated Native Americans in the AEF."

On the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier's significance in American history

"This is hallowed ground. It's sacred ground. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier represents all who served, and who have fallen, for the United States."

Book Excerpt: 'The Unknowns'

by Patrick O'Donnell

“Fix bayonets!”

The piercing shriek of Marine whistles and guttural bellows of “Follow me!” trailed the order as men of Gunnery Sergeant Ernest Janson’s 49th Company emerged from the woods. Dawn turned gray, and light bathed the flowing fields of wheat that lay in front of the men. “Dewy poppies, red as blood” were sprinkled randomly through the waist-deep wheat.

The Marines advanced in Civil War–style formations.* As they gazed to their right and left, they viewed a panorama largely untouched by the Great War: sinuous hills of grain, clumps of trees, and a lush, verdant forest that served as a hunting preserve prior to the war. The dense kidney-shaped woods known as Bois de Belleau occupied roughly one square mile of land. Two deep ravines cut through the trees, and massive boulders, some the size of a small building, littered the ground, making Belleau Wood a natural fortress. A ridge 142 meters high, and therefore dubbed Hill 142, sprawled to the west.

An angry red sun emerged just above the horizon in the cloudless blue sky behind the men’s backs. Many turned their heads, some for the last time, to glimpse the blazing sunrise. At that instant, German shells and machine-gun bullets ripped through the golden farmland, striking flesh and bone.

*To attack Hill 142, the platoons formed into assault waves. Only two companies advanced. The Marines planned to advance with five—including machine gunners—but the other three companies had not entered the line at 3:45 a.m. for the start of the assault.

As men began toppling like dominos, Marine officers screamed, “Battle-sight! Fire at will!” Their voices broke through the din of the battle and anguished cries of wounded and dying men.

Only two companies from 1/5, the 49th and 67th, had arrived at the jumping-off point prior to 3:45 as instructed. The battalion commander of 1/5, Major Julius Turrill, who had received the order to attack Hill 142 only hours earlier, had earmarked five companies, or nearly one thousand men, for the assault. Short and stocky, Turrill had served in the Philippines, Cuba, and Guam, as well as on various ships. Unbeknownst to the attackers, the Marines faced a battalion from the German 460th Regiment and a battalion of the 273rd Regiment (both understrength), including several machine-gun companies. The hill lay on the boundary between the two German divisions. Fortunately for Janson and the 49th, the enemy had not dug in, and a command dispute prevented the two Boche units from tying together for maximum defense. Nevertheless, the Germans vastly outnumbered the two Marine companies.

The 49th’s commanding officer, Captain Hamilton, led the Marines toward Hill 142. A rugged former football captain, exceptional athlete, and fighting Marine officer, Hamilton never asked his men to do anything he would not do personally. Before the charge, he realized the men “were up against something unusual, and ran along the whole line to get each man (almost individually) on his feet to rush the wood.”

Armed with Springfield rifles, Hamilton and Janson fired into the woods at field-gray German gunners wearing camouflaged Stahlhelms on their heads. While Janson, Hamilton, and most of the Marines carried the M1903 rifles, other men armed with the fully automatic Chauchat machine gun fired from the hip, laying down a heavy spray of lead as they surged toward the German gunners.

Its height in meters led to 142’s designation as a hill, but in reality, the slope was more of a ridge that jutted from north to south in front of the Bois de Belleau. Patches of woods and wheat fields and ravines bracketed the mound, which dominated the battlefield. Both sides coveted 142’s high ground and would fight to the death to possess it.

Although many of their brother Marines lay dead or wounded in the grain, Janson, Hamilton, and other men in the 49th emerged unscathed. They descended on the Germans, quickly hurling grenades, plunging the blued steel of their sixteen-inch bayonets into the bodies of the enemy, and dispatching others with small arms fire. Later, Hamilton had vague recollections of “snatching an Iron Cross off the first officer . . . and of shooting wildly at several rapidly retreating Boches.” He added, “I carried a rifle on the whole trip and used it to good advantage.”

The 67th did not fare so well. Lieutenant Orlando C. Crowther, its leader, and 1st Sergeant “Beau” Hunter both died from wounds inflicted by Maxim nests concealed in a ravine. Hamilton and Janson reorganized what was left of the shattered platoons in the 49th and 67th. Then they had to do it all over again: yet another open wheat field lay in front of the murderous fire of several companies of German machine gunners defending Hill 142.

Once again, the Marines burst from cover and waded through waist-high wheat. Hill 142 loomed ahead, crested with pine trees that ominously appeared black as they reached skyward against the back- ground of the blue sky. Colored tracer rounds from the Maxims whizzed by the Marines, and German rifle and machine-gun fire cut through the front ranks. Most of the men dove to the ground, prone, hoping the fragile stalks would obscure the gunners’ line of sight.

A Marine officer barked, “Can’t walk up to these babies. No—won’t be enough of us left to get on with the war. Pass the word: crawl for- ward, keeping touch with the man on your right! Fire where you can.” Within minutes, the officer went down—a dozen Maxim bullets having ripped through his chest.

Another squad of Janson’s men aimed to take out a Maxim crew. A corporal from the group got beyond the gun and tried to flank it. Attempting to coordinate their actions, one man yelled, “Get far enough past that flank gun, now, close as you can, and rush it—we’ll keep it busy.” After maneuvering into position, the corporal shot up and, with a yell, attacked the gun. Keeping their promise, his brothers backed him and charged the gun. One member of the 49th remembered the grisly result after two gunners turned their weapons on the charging Marines: “[Their Maxims] cut the squad down like a grass-hook levels a clump of weeds. . . . They lay there for days, eight Marines in a dozen yards, face down on their rifles.”

Some Marines, repeatedly wounded, forged ahead. One small group of men from the 49th lay in wheat in front of the muzzle of a German machine gun. Bullets zipped by and “clipped the stalks around their ears and riddled their combat packs—firing high by a matter of inches and the mercy of God.”

One member of the 49th explained: “A man can stand just so much of that. Life presently ceases to be desirable; the only desirable thing is to kill that gunner, kill him with your hands!” He added, “One fellow seized the spitting muzzle and up-ended it on the gunner; he lost a hand in the matter. Bayonets flashed in, and a rifle butt rose and fell.” Janson’s and Hamilton’s Marines improvised their tactics on the

fly. Small groups of determined men surmounted the seemingly impossible with their iron will, taking out one nest after another as they rolled up the hill. Later Hamilton noted, “It was only because we rushed the positions that we were able to take them, as there were too many guns to take in any other way.”

The Marines had the enemy on the run. They took out several more nests; the Germans seemed to melt away. With resistance waning, Hamilton pulled out his map case and scanned the area for an unimproved road that appeared on the map. With only a platoon of men, including Janson, Hamilton set out for the road, moving over the nose of Hill 142 in the process. Unbeknownst to them, that road led to the German-held village of Torcy.

On the road, the men found themselves in a cleared area scattered with woodpiles. Hidden behind the piles, several Maxims started firing upon them. A stream of bullets struck one Marine. “The man’s head was gone from the eyes up; his helmet slid stickily back over his combat pack and lay on the ground.” A Marine picked up the man’s Chauchat and pulled the trigger back, unloading an entire half-moon-shaped magazine into three oncoming Germans, who appeared to “wilt.”

Excerpted from THE UNKNOWNS: THE UNTOLD STORY OF AMERICA’S UNKNOWN SOLDIER AND WWI'S MOST DECORATED HEROES WHO BROUGHT HIM HOME copyright © 2018 by Patrick K. O’Donnell. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on May 28, 2018.

This segment aired on May 28, 2018.