Advertisement

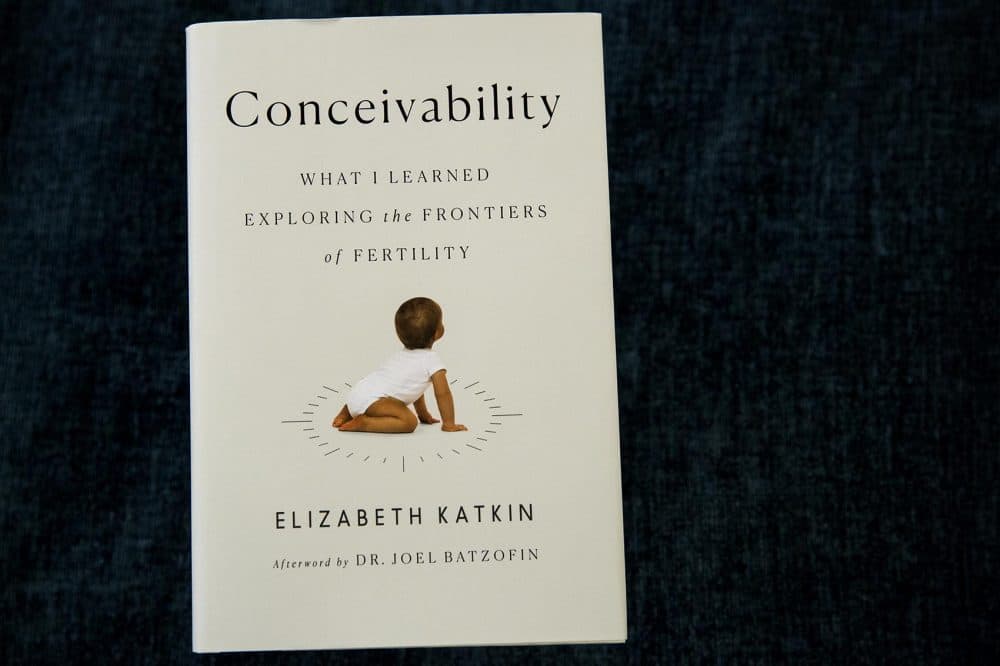

'Conceivability' Follows One Woman's Journey Through The Global Fertility Industry

Resume

When Elizabeth Katkin and her husband decided to have children, it took nine years and involved multiple miscarriages and in vitro fertilization treatments. They eventually had two healthy children, but Katkin's experience inspired her new book.

Katkin (@LizKatkin_books) joins Here & Now's Femi Oke to talk about "Conceivability: What I Learned Exploring the Frontiers of Fertility."

Interview Highlights

On her efforts to become pregnant

"I definitely didn't start out as a person who felt like, 'Oh I have to have a baby no matter what.' Part of what happened to me is that I did get pregnant, and things kept going wrong. And it was a little bit like a dog with a bone. I mean it was a science project for me: No one could explain why I couldn't get pregnant easily. And more than that, no one could explain why I kept miscarrying. So each time I would get pregnant, and then I would miscarry, I would think, 'Well I just got pregnant, I can do it again.' And I just sort of kept trying, it was like a hamster in a Habitrail, and you can't get out."

"No one could explain why I couldn't get pregnant easily. And more than that, no one could explain why I kept miscarrying."

Elizabeth Katkin

On how difficult the journey was

"Wow, let's see. It's quite a list. I had seven miscarriages. I did [in vitro fertilization] 10 times — that was eight fresh IVF cycles and two frozen. I had five natural pregnancies, so natural was without assistance at all, four IVF pregnancies. I saw 10 doctors — four of whom insisted I give up trying — in six countries. I worked with two potential surrogates. It took us nine years. My husband and I spent close to $200,000."

On financial tips for couples trying to have a baby

"One which I didn't learn until very late in the process was that a lot of insurance that won't cover IVF or reproductive procedures will actually cover the tests that will help you figure out what's wrong, and those tests themselves can be very expensive. So one woman, for example, Rose, who I interviewed — who'd spent loads of money and had gone through three cycles, and she'd spent about $70,000 and still didn't know her problems — learned that having her regular OB-GYN order diagnostic tests was fully covered by her insurance, while those exact same tests were denied with a fertility clinic, because if it was seen as fertility, it wasn't treated, but if it was seen as diagnosing a gynalogical problem, that was covered. So really simple tricks like that, like getting as many tests covered by insurance as you can.

"Or if you work in the right sector, switching jobs. I spoke extensively with a woman named Rachel who's in IT, and she figured out that if she got a job at Apple, all of her infertility would be covered. So she switched companies and picked up insurance.

"And traveling — traveling is a big one, whether that's U.S. or domestic. I spoke with a couple who were from Boston originally, but had their entire professional lives been outside of Massachusetts, and they decided to move back home to Massachusetts where their IVF would be covered. And they have a healthy daughter now. And similarly, traveling to places like Spain, Prague, Russia — there's a host of countries with fabulous IVF programs with very high success rates and much lower costs."

"A lot of problems are solvable, but it takes a lot of thought and brainpower to get to the right solution. And you have to be a proactive part of your own care."

Elizabeth Katkin

On health tips she learned along the way

"Rest is important, nutrition's important, getting the right vitamins is important. I mean there's loads of research now that shows that certain B vitamins — B6 and 12 and omega-3 and CoQ10 — they have really important impacts on egg development and egg quality, and egg quality is something I think we really don't focus on enough in this country. That's probably the single most important element I learned in all of my travels to all of these countries, was how much other countries are focused on the quality of eggs over the quantity, and in the U.S. for the most part, many of the doctors and clinics I encountered are focused on the quantity. I think in the U.S. in general, with everything, more is better. But with fertility, is more really better? It only takes one egg to get pregnant.

"And so getting the healthiest egg possible is a really key part of the process, and that can be things like food, eliminating plastics with BPA, we've all heard a lot about how BPA is bad. And also really talking to your doctor about the level of hormones, that was my probably single most shocking moment in the fertility journey, was to learn that a lot of the high levels of hormones I'd been injecting through rounds and rounds of IVF may have actually been damaging my eggs, which explain in part why I kept getting pregnant and kept losing them."

On what she would say to a couple having trouble getting pregnant

"I would tell them that the most important thing is to really take control of the situation. Knowledge is power. And what I found in my own experience — and I interviewed dozens and dozens of women and couples, and gay and straight couples — is that most people who are successful had an aha moment, this moment where they realize that they can't just be funneled through the system and they have to take charge. It's asking the right questions, and not being afraid to keep asking questions until you understand the answers: 'What exactly is my problem? Why do you think this protocol is going to work for me.' That sounds quite simple, but really forcing the doctor to look at you and not pick one or two protocols off the shelf. A lot of problems are solvable, but it takes a lot of thought and brainpower to get to the right solution. And you have to be a proactive part of your own care."

Book Excerpt: 'Conceivability'

by Elizabeth Katkin

If you have to write a book, why can’t you write a book about recipes, like how to make cookies?” asked my then five-year-old daughter, with her impish little grin.

I scooped out the dough onto a baking sheet, smiling. “Because I want to write a book about how to make babies,” I answered, “so that other parents can have wonderful babies like you and your brother.”

Alexandra looked at me, her striking green eyes wide with indignation.

“I am not a baby,” she cried.

“You know what I mean,” I replied. “You were a baby.”

“But having babies is easy,” Alexandra declared. “Everybody has babies.” She twirled around on her toes, practicing to be a ballerina.

“When I grow up, I am going to have a girl and a boy. An older sister and a younger brother. Sarah and Henry.”

“Just like that?” I asked.

“Just like that.”

I had thought so too. Like Alexandra, I used to believe I would grow up and get married and have two children, one boy and one girl, just like my parents did. Just like that.

I never thought for even a second about the possibility that it might not happen. Until the time came when I actually tried to get pregnant, my only pregnancy concern had been ensuring that it didn’t happen accidentally. I looked at my beautiful daughter practicing her ballet steps in the kitchen and, not for the first time, marveled at her very existence. If she only knew the amount of time, energy, and money—not to mention the physical and emotional ordeal—that her father and I had gone through over the last decade to create her and her brother.

I never could have imagined that my quest for children would ultimately look like this:

Seven miscarriages

Eight fresh IVF cycles

Two frozen IVF attempts

Five natural pregnancies

Four IVF pregnancies

Ten doctors (four of whom told me to give up trying)

Six countries

Two potential surrogates

Nine years

$200,000

That’s my recipe. And now my husband and I have two beautiful, healthy children. One boy and one girl. Just like that.

I am an accidental fertility expert. I did not go to medical school, and did not, in my college and graduate years, prepare to devote myself to helping other women, let alone myself, get pregnant. Fertility was not something I ever thought about, until confronted with years of “trying” and the devastating pain of my first miscarriage—sadly followed by six additional miscarriages and almost a dozen failed IVF attempts. Yet I surprised even myself in my absolute, unshakable refusal to take no for an answer. In the face of overwhelming challenges, I gradually undertook my own quest to find solutions.

In so doing, I was willing to sacrifice a lot—too much, some might say, and some did. I submitted my body to punishing rounds of fertility treatments of every kind. I was willing to spend every cent of our life savings. I saw doctors at top clinics in six countries—the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia—and educated myself on state-of-the-art Western practices, as well as ancient Eastern and traditional approaches to overcoming infertility. I tried intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), and in vitro immunoglobulin (IVIG). I worked with egg donors and surrogates, and completed an adoption home study. I drank Chinese herbal teas, served as a cushion for an uncountable number of acupuncture needles, and took a variety of homeopathic remedies and tinctures derived from Germany to the Arabian Peninsula. I wore a fertility necklace, touched a fertility stone, and sat under a fertility tree. Alternately a fan and a skeptic, and ultimately a realist, in my 3,285-day crusade to complete my family, I left no stone unturned, and I opened my mind to paths previously unknown to me.

I know I must sound like a zealot. I didn’t start out that way. I was just a stubborn woman who wanted to have a baby, who wanted to understand why she was having difficulty, and who wanted to fix whatever was causing it. What was happening in my body? Why couldn’t the doctors answer my questions? If there had been an explanation—a credible explanation—for what was wrong, I might have accepted it and moved on. But I had been trained as a lawyer, and I thought like one, and the reasons I was given didn’t make sense to me and didn’t hold up under interrogation.

….

So I did what lawyers do. I looked for answers in the facts.

Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Katkin courtesy of Simon & Schuster

This article was originally published on June 21, 2018.

This segment aired on June 21, 2018.