Advertisement

Inside The Biggest Private Real Estate Development In U.S. History

Resume

To hear the March 14, 2019 rebroadcast of this story, click here.

When the outdoor observation deck at 30 Hudson Yards in New York opens to the public late next year, it will be the highest of its kind in the Western Hemisphere — so high that standing on the edge will make you feel uncomfortably close to the clouds.

The deck, rising more than 1,000 feet over Manhattan, is just part of the greater Hudson Yards project, the largest private real estate development in American history. Located on the West Side of midtown Manhattan, the finished project will include a mix of skyscrapers, public space and other amenities with major companies housing their headquarters in office buildings, residential spaces to rent or to own, a large retail complex and a performing arts center.

Total square footage: Around 18 million.

Total price tag: $25 billion.

The Hudson Yards development is expansive, and it hasn’t been without its challenges — and its critics.

A New World Trade Center?

It’s hard to ignore the comparisons between this development — a city within a city — and a similar project that opened at the southern tip of Manhattan in 1973: the original World Trade Center.

It’s a comparison that isn’t lost on Jay Cross, who heads up the Hudson Yards project for the developer, Related Companies.

“I mean not only was it a similar dream, I think in its day, it achieved similar results,” he says. “In terms of raw ambition and demand, it was a great example of what we’ve done here.”

While they stood, the Twin Towers were a symbol of New York’s — and America’s — economic dominance. But after Sept. 11, 2001, they became a symbol of tragedy. And now there’s a fear that any new project in Manhattan of this scale could also one day be a target for terrorists.

“Any large development today has to be concerned about that,” Cross says. “So we devote a lot of time and energy to security. We want people to feel inherently safe, but we don’t want people to feel like they’re in an armed camp.”

Something For Every New Yorker

“I think the dream is to create a new urban environment, the likes of which we haven’t seen before, that’s responsive to the 21st century,” Cross says.

He pictures an ecosystem where people leave their open office spaces at the end of the work day, walk across the square to their apartment, hop into workout gear for a ride at SoulCycle and meet friends for dinner at a Jose Andres restaurant — with no need to leave the area.

“It’s creating a mixed-use environment that’s vibrant 24 hours a day, that is diverse in lots of different ways, and has something to offer everybody,” he says.

To some, the vision feels akin to Las Vegas. And parts of it resemble an upscale shopping mall.

“We don’t like to use that word because a mall is generally one level, a horizontal suburban exercise,” Cross says. The retail space is “seven levels, and seven levels in America is very unusual.”

Creating a neighborhood from scratch is no easy feat, and many critics say that in doing so, Hudson Yards will fail to capture the vibrant, organic nature of New York. But Cross says developers have a vision to “create a sense of place quickly” in the planned development.

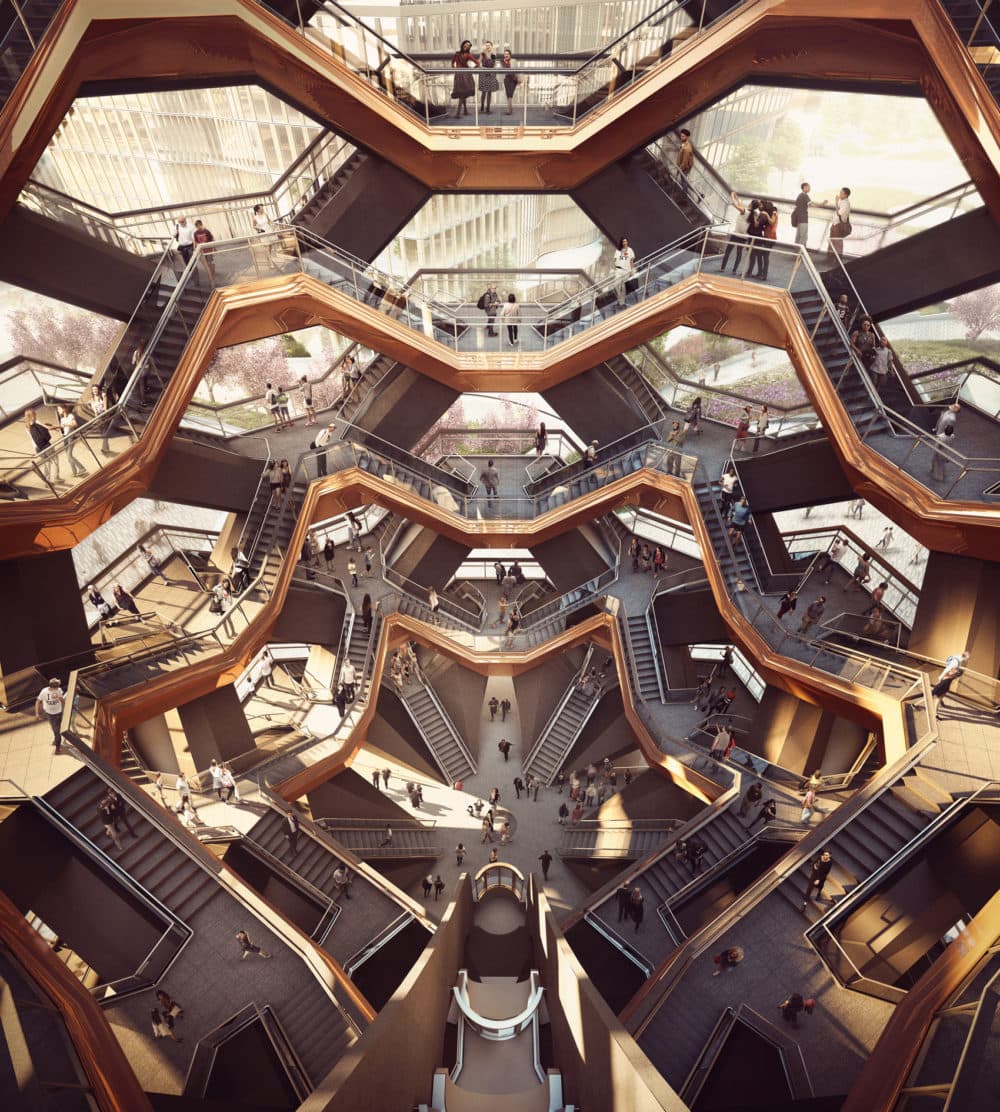

“While we would say retail, residential and commercial are the three essential components of a mixed-use community, what’s really important is that you’ve got to intensify those uses,” he says. “And you intensify them with all the little things that you do in between those uses — like the public space, the gardens, The Shed, the Vessel, the observation deck and mass transit.”

The company sees shared public space as a great way to attract New Yorkers and tourists who don’t live in the area. But living there will be pricey. Rents at One Hudson Yards, the 178-unit luxury apartment building that opened in 2017, start at $5,400 a month, while condo prices in the neighborhood exceed $3,000 a square foot on average.

Housing advocates also worry the West Side development will worsen New York’s already sky-high cost of living. The city requires 25 percent of the units in Hudson Yards to be set aside as affordable housing. The developer says the project will contribute around $19 billion to the city’s GDP and add around $500 million a year in tax revenue.

Infrastructure Challenges

A project this large has unique infrastructure challenges, especially in a city still recovering from the damage of Superstorm Sandy.

“We did a few things differently as a result of Sandy,” Cross says. “Our ground floor ... is more like 40 feet above sea level, and that’s above the 500-year flood [line]. So the idea that we would ever have water in our ground floors is pretty remote.”

Still, the developer took precautions to protect elevator control systems, and there’s a backup plan to get power in case another big blackout hits the city.

Attracting tens of thousands of new workers to the area could also strain the public transportation system in New York and New Jersey. Part of the solution involves building a new $2.4 billion subway station, and extension of the No. 7 train line. The extension opened in September 2015.

The 34th Street-Hudson Yards station is the first addition to the transit system in 26 years, according to the Metropolitan Transit Authority. The agency expects it to be one of the busiest station stops in New York, though ridership has been significantly lower than predicted.

“It’s all a question of scale: 600,000 people a day go into Penn Station; we have 40,000 office workers, only about 10,000, 15,000 of those office workers come in through Penn Station,” Cross says. “Are we really going to move the needle on Penn Station? I don’t think so. Is Long Island Railroad and New Jersey Transit going to increase capacity? Absolutely, they have to. That’s the goal for the region.”

Cost is also an issue. Related says that the project has gone over budget due to an ongoing labor battle with the city’s powerful construction unions.

In 2013, Related and the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, an organization representing nearly 100,000 construction workers, signed an agreement to build the first section of Hudson Yards. Unionized workers agreed to a certain budget and work rules. But after the BCTC allegedly inflated costs by some $100 million, Related hired nonunion workers, according to lawsuits.

Labor leaders argue that Related is squeezing workers into agreements that significantly reduce wages and work standards. But, they say, if the unions don’t enter into these agreements, their workers won’t be able to compete. A carpenters’ union recently broke away from the BCTC to negotiate with the developer separately.

At an April protest of Related’s labor practices, union electrician David Stronger told The New York Times, “I think about half our work now is nonunion. Without the unions, it’s a race to the bottom. They pay as little as they can. It doesn’t just hurt us, it brings the whole economy down.”

The Bigger Economic Picture

It’s been 10 years since the financial crisis, but an economic downturn happens every nine or 10 years on average, according to historical patterns.

Cross says recessions are to be expected and diversity in Hudson Yards will help mitigate some of that risk.

“When you take on a project like this, you have to build into the fact that over 20 years, you’re going to hit one or two recessions,” he says. “We’ve insulated ourselves. We’re not industry specific. We have the leaders of media, the leaders of fashion, the leaders of tech, the leaders of private equity, the leaders of hedge funds, the leaders of banks. We’re in every major industry type in New York, and I think we’ve got a lot of built in resiliency there.”

30 Hudson Yards is just one of many skyscrapers currently going up across the U.S., including the Vista Tower in Chicago, the Capitol Tower in Houston and the Wilshire Grand, which just became the tallest building in Los Angeles. Business experts say new luxury developments are attracting industry to established urban hubs.

“In many respects, it represents the ability to cater to work in the 21st century,” says Jason Barr, economics professor at Rutgers University who has written a book about Manhattan’s evolving skyline.

“Much of the growth in the American economy is taking place in older urban centers like New York,” he adds, “so to the extent that a place like New York can continue to grow and continue to accommodate the kind of growth important to the 21st century, then I think that's important to the United States as a whole.”

This segment aired on August 13, 2018.