Advertisement

Monty Python's Eric Idle Looks Back On The 'Bright Side' Of A Life In Comedy

Resume

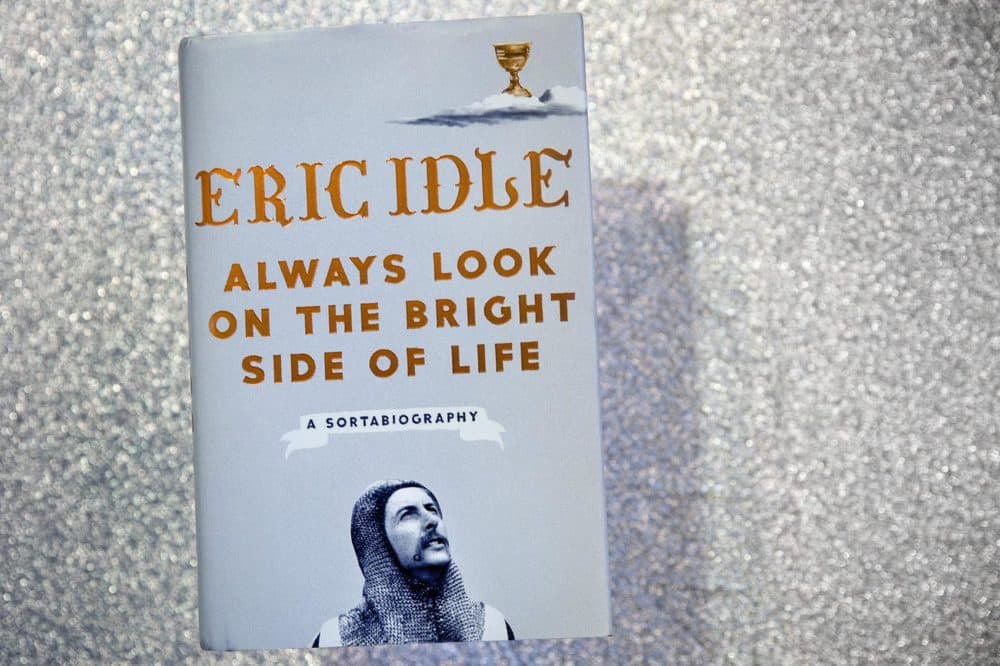

Editor's Note: This segment was rebroadcast on October 1, 2019, after "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life: A Sortabiography" was released in paperback. That audio is available here.

Monty Python co-founder Eric Idle's memoir "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life: A Sortabiography" comes out Tuesday.

Here & Now's Robin Young talks with Idle (@EricIdle) about the book.

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life"

Interview Highlights

On the impact the early 1960s British stage comedy "Beyond the Fringe" had on him

"They were the first people really I ever saw who actually attacked the prime minister or the cabinet or the queen and the royal family, the Army, the Navy, religion — and they just demolished everything. I just thought, 'Oh my gosh, you can be funny about all this stuff.' "

On how growing up after World War II shaped Monty Python members

"We we all born in the war, and then we grew up in the '50s, which was a time in England where there was rationing of everything: butter, cheese, sugar, beef. So there was very great shortages. London was filled with bomb sites, everything was blitzed and horrible. What was interesting is that that generation, as they matured and became teenagers, invented everything: rock 'n' roll, photographers became wonderful at photography, there was couture — because there was nobody else there. They'd all either been in the army or just coming home. So there wasn't anybody ahead of us. So in a way, that was a wonderful blank canvas, and we got really lucky, because they weren't saying, 'Oh you're just like that show we had three years ago.' There wasn't a show three years ago."

On people still using phrases from famous Python sketches

"It's kind of humbling, especially when you realize that next year is the 50th year since we started doing this stuff in 1969. And that's sort of unusual to me. Things don't tend to survive that long, and I think it's very humbling and rather wonderful."

On the 1978 mockumentary film "The Rutles," which he directed

"It's really about Beatlemania, and the madness that surrounded it and how the press talked about it. It was the first mockumentary ever made. I'm rather proud of that. Lorne Michaels of ['Saturday Night Live'] produced it, and it was on NBC first. So it was very nice. I had Belushi playing the managers. Bill Murray played a disc jockey ... Dan Akroyd was in it, all those early 'SNL' people came and joined the company. And it was good fun."

On the prospect of "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life" being sung at his own funeral

"Almost inevitably, because it is the No. 1 song requested at British funerals. It's kind of an optimistic, sweet-sour song for people to sing at a funeral. It gives them a laugh, and it moves them. I think it's rather a healthy song, about the inevitability of all our ends."

On one of his favorite Python moments

"[Monty Python member] Michael Palin used to have one which he always loved, because he was a trainspotter. So I wrote one about camel spotting, and he said, 'How many have you seen so far?' And I say, 'Not any so far, but I'm still waiting. I've got the book and a pencil.' "

Editor's Note: The book excerpt below contains some explicit language.

Book Excerpt: 'Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life'

by Eric Idle

The miracle of Brian is that it got made at all, which was entirely due to the generosity of George Harrison. Asked why he mortgaged his Henley home to pay for the entire $4.5 million budget of Monty Python’s Life of Brian, he said, “Because I wanted to see the movie.”

It’s still the most anyone has ever paid for a cinema ticket.

The idea for Brian had sprung from an ad-lib I made at the opening of The Holy Grail in New York in April 1975.

Journalist: Mr. Idle, what is your next film going to be?

Me: Jesus Christ, Lust for Glory.

Interestingly, the Pythons began to take my gag seriously. Gilliam and I improvised disgracefully on the theme one drunken evening in Amsterdam, using highly blasphemous jokes, for which I blame the beer, but it was John Cleese who really liked the idea of doing something about religion. Nobody had ever done anything on the subject. It was a big blank space for comedy. We began by doing research, reading biblical history, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Apocrypha, some of the weirder books that never made it into the Bible. We screened some of the hilarious Hollywood movies made about Christianity: The Robe, The Shoe, Ben-Him, Ben-Her, you know the sort of thing. They were magnificent mainly for the appalling acting of major Hollywood stars that made us laugh a lot.

John Wayne: Shirley this man was the son of Gawd.

We agreed early on, you couldn’t knock Christ. How can you attack a man who professes peace to all people, speaks out for the meek, heals the poor, and cures the sick? You can’t. Comedy’s business is some kind of search for truth. Clearly this was a very great man, leaving aside for a minute his potential divinity. No, the problem with Christianity was the followers, who would happily put each other to death at the drop of a dogma. You could be burned alive if you didn’t believe Christ was actually in the Communion wafer (what, cannibalism?), and they are still bickering about whether gluten-free bread constitutes the real Christ or not. I mean, it’s nuts. Christ admired, saved, and protected women. The followers denied them, locked them up, and insisted in about the twelfth century that the clergy become celibate, with highly predictable results, from popes shagging their daughters to pedophilia.

What we needed for our purposes was a surrogate for Christ. So Brian was born. For a while he was just one of the followers. He was given the job of trying to book a table for the Last Supper:

“Sorry, mate, it’s Seder; we’re fully booked.”

“No, we can’t do a table for thirteen. I can give you one of six, and then another for seven over by the window.”

“Why don’t you want to use both sides of the table?”

At this stage Brian was just a writer, like the other followers who gave the Messiah tips on his speeches: “Lose the bit about the meek, they’ll be too timid to turn up anyway, hit ’em with a couple of beatitudes, the parable about the Samaritans plays good, render a bit unto Caesar so as not to offend the Romans, and then end with the trick of changing the water into wine. That’s always very popular, everybody has a good drink and you’re home and dry.”

People say, “Oh, you’d never make fun of Mohammedans,” and of course not. We’re not Muslims. We were brought up as Christians. I was sent to church twice every Sunday from the age of seven to nineteen, and I loved the language of the King James Bible. I must have heard it read aloud at least three times in chapel. At the age of fourteen I was confirmed by the Bishop of Something, and I even for a while was a believer, but when a boy asked our Padre at school whether he thought Jesus was the son of God, he surprisingly answered: “Well no, old bean.” That from the Padre. So, we had earned the right to examine Christianity, and we treated it seriously. People who thought we were attacking Jesus clearly never saw the movie. He is in the film twice: once at his birth, where it is made very clear that Brian is born next-door and the Three Wise Men have come to the wrong stable, and once at the Sermon on the Mount, where the crowd at the back, quite reasonably, can’t hear very well.

“I think he said, ‘Blessed are the Greek.’ ”

Our movie became about the followers, the interpreters, the exploiters, and the profiteers, the people who seek to control those who wish to believe. A perfectly legitimate target for satire, and one appreciated by many people in the Church, who understood the joke is not about Christ, but about man.

“Or woman.”

Yes, alright, Stan.

To avoid cheap blasphemy gags, and really examine the subject, Brian became a man who suffers the awful fate of being mistaken for the Messiah. A terrible nightmare. No matter what he does or says, he cannot refute it.

“I’m not the Messiah.”

“Only a true Messiah would deny his divinity.”

“Well, what chance does that give me? Fuck off.”

“How shall we fuck off, O Lord?”

Brian, of course, is a tragedy. Pursued by his followers and wanted by the Romans, he is captured and sentenced to death by crucifixion, then the major form of execution used throughout the Roman Empire.

“What will they do to me?”

“Oh, you’ll probably get away with crucifixion.”

“Get away with crucifixion?”

“Yeah, first offense.”

Mass crucifixions were common. Two thousand of Spartacus’s followers were crucified along the Appian Way. Some were even set alight. (An early form of street lighting.) There is nothing special about crucifixion. In a different century Christ would have been hanged and his followers would all now wear nooses. But in March 1976 it gave us a big problem with the script. With Brian and many of his followers headed for death, how on earth were we going to end the film?

I had a lightbulb moment.

“Well, it has to be with a song,” I said.

“What?”

“A song. Sung from the crosses. A ridiculously cheery song about looking on the bright side. Like a Disney song. Maybe even with a little whistle.”

And they laughed.

“Like a sort of Spartacus musical,” said someone.

“They can dance, too,” said Gilliam with a gleam in his eye.

And they laughed at the idea that it could become a big production number.

And then everybody said, “That’s it! We’ve got our ending. Hooray, let’s go home for the day!”

So, it went into the script as “I’m Looking on the Bright Side,” and I said, “I’ll write it up,” and I took home some notes I’d scribbled on the back of the script, got my guitar out, and it didn’t take very long at all.

The first thing I wrote was the whistle (G/Dm7/Am7/E7) using jazz chords that I had learned from the Mickey Baker guitar course. It took me maybe twenty minutes to sort out the basic shape of the song using major sixths and minor sevenths and the very useful diminished chord, which George Harrison told me the Beatles called “the sneaky chord.” The verse also appeared very quickly: Am7/# (sneaky)/G/Gmaj6 / Am7/# (sneaky)/G and the words flowed quite simply. After about an hour I had to stop and collect Carey, who was now three years old, from nursery school, and I remember driving home in a hurry so I could play him what I’d written. He really liked the song with its whistling chorus. I had changed the lyric to “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” to fit my tune, and I recorded it then and there on a little Sony tape recorder, which I still have, and played it the next day to the rest of the chaps. They seemed to like it.

Excerpted from the book ALWAYS LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE OF LIFE: A SORTABIOGRAPHY by Eric Idle. Copyright © 2018 by Eric Idle. Republished with permission of Crown Archetype.

This segment aired on October 2, 2018.