Advertisement

Brexit: Before The Breakup

London's New Elizabeth Line Aims To Help Millions Traverse The City Faster

Resume

London is famous for its Tube. It's the oldest underground rail network in the world — but it's also very crowded. Nearly 5 million people use the Tube every day, and at peak hours more than 500 trains are zipping below one of the world's busiest cities.

That's why Londoners were unhappy to learn earlier this year that the Crossrail project had been delayed. Crossrail, a 15 billion-pound moonshot that will cut down travel times across the city and bring relief to commuters, is one of Europe's biggest infrastructure projects.

The project is held in such high esteem that two years ago, Crossrail was renamed the Elizabeth line in honor of Queen Elizabeth II.

But the queen will have to wait another year to ride the Elizabeth line, which is now expected to open in fall 2019. That means Howard Smith, Crossrail's director of operations, is a man under pressure.

"The hardest part of the job is to bring all of it together — old and new systems, the train, the signalling," Smith tells Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson. "There's three different sorts of signalling, so you have to bring those together and test them. Nobody wants to open something that isn't reliable, you would never open something that wasn't safe. So we're continuing to test."

Interview Highlights

On the vision behind the project

"The Elizabeth line's about physically building some new tunnels, about 14-15 miles of new tunnels ... right through the heart of London. But those tunnels actually connect up the existing lines that run to the mainline termini in London.

"For ... well over 100 years, people in London — in fact in most European cities — have been used to coming to the edge of town in a big train above the surface, and then doing something that's very odd, when you think about it, which is to go on an escalator down and get in a small train to finish off the journey across the center of London. That's because, over 100 years ago, you couldn't easily build tunnels because it was steam trains, they don't fit very well with tunnels, and also there was a law that stopped railways coming into the very center of London.

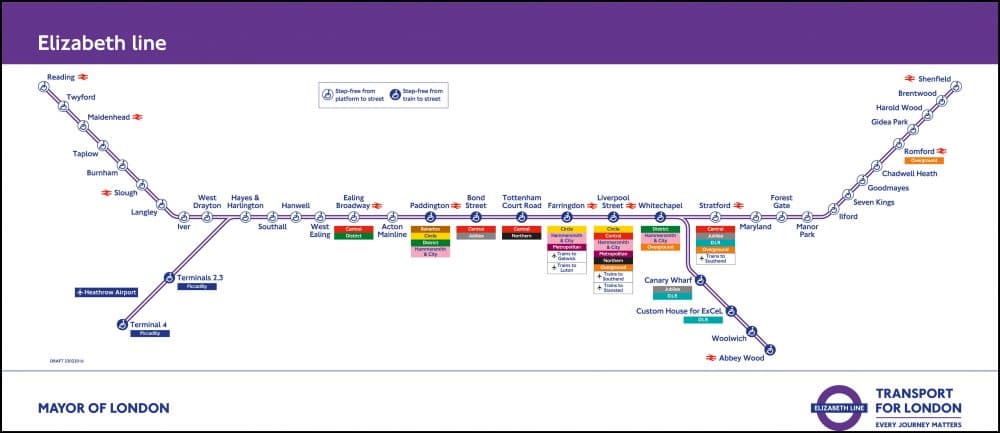

"The Elizabeth line in total will connect Heathrow Airport, the West End, the area just used for the Olympics at Stratford — so all of London's major areas all connected up on one new line."

On constructing these tunnels without disrupting the city above

"The tunnels that have been dug across London are fairly deep. They're not cut-and-cover tunnels where you go down from the surface. They're actually [built using] tunnel-boring machines — there were eight huge, 100-meter-long factories underground, tunneling under London. So they're about 30-40 meters below the ground. The reason they're able to get through and have a good alignment is because actually the route has been protected under planning regulations for decades. So the route was planned, and then the tunnel-boring machines set off from the edge of town and essentially worked towards each other. ... It took about four years to do the tunneling."

On how Crossrail's routes were preserved for so many years before the project began

"Crossrail's been under planning — depending on quite how you want to call it — for over a century. The Regent's Canal Company actually had plans for an east-west railway across London back in the 19th century. Something called the Abercrombie report at the end of the Second World War laid out London's future transport links, and included something that we'd recognize as Crossrail today. So actually the history of these things — even things like the [English] Channel tunnel — are that the good ideas don't go away."

On the biggest challenge of Crossrail

"[There have been] many challenges in Crossrail, and I've been on the project for about 15 years. Probably the first one was actually to get 15 billion pounds together, jointly funded by the city and by government — huge challenge. And then the real difficult bit — but I'm slightly biased as the operator at the end of it — is actually bringing all the pieces together. So, something as complicated that connects up existing railways, brand-new railways, new systems, old systems — that's the real challenge at the end of the job."

On why this project was possible in London, while projects in U.S. cities — like New York's Second Avenue Subway — have proven more challenging to complete

"Lines like this — really big, high-capacity expensive lines — only make sense in really big cities, so that narrows down the field a bit. The other challenge which does apply in Europe but perhaps not quite as much as it does in North America is actually bringing the various funding streams together. In North America, you end up having to assemble a huge number of different funding streams that often take a long time to bring together, because they're dependent on different politicians. ... We had to do that for Crossrail, but we had to do that simply between the London mayor and the government."

Peter O'Dowd and Alex Ashlock produced this interview and edited it for broadcast. Jack Mitchell adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on November 15, 2018.