Advertisement

Want To Know How To Ask Questions? Longtime Journalist Shows How It's Done In New Book

Resume

With the rise of podcasting and the lack of civil conversation he was seeing around him, author and longtime journalist Dean Nelson (@deanenelson) says it struck him as a perfect time to write a book demystifying the art of asking others questions.

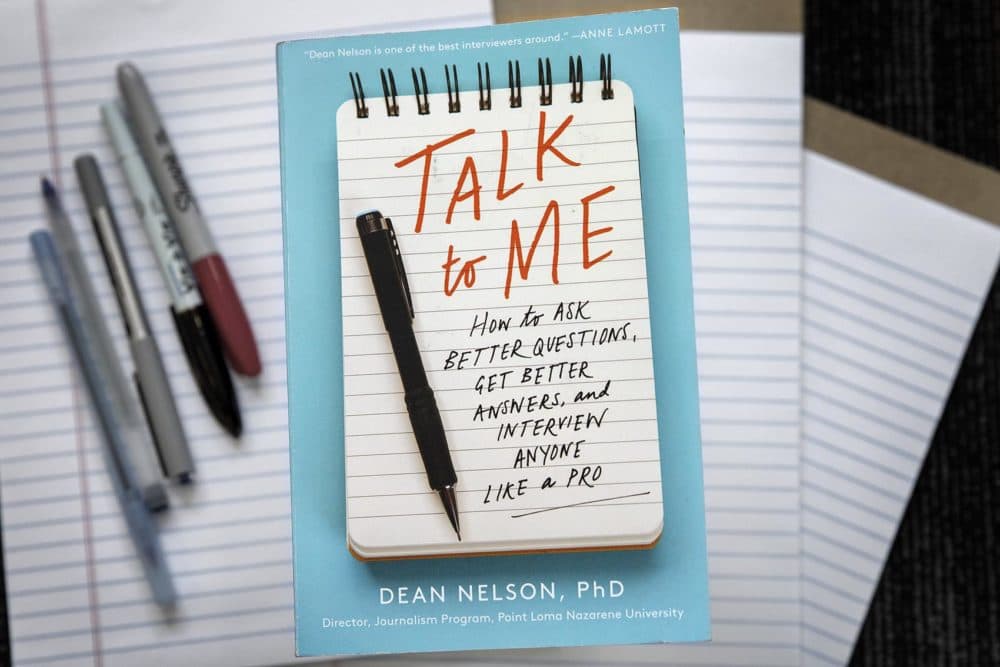

“It just felt like, well, I know something about it. I think the world needs it, and there is this rising interest in long, deep conversation, either through podcasts or I think just in civil life,” says Nelson, who recently released his new book, “Talk To Me: How to Ask Better Questions, Get Better Answers, and Interview Anyone Like a Pro.”

Preparation ahead of time, asking open-ended questions, always recording yourself and your subject — there are a lot of factors that go into a good interview, says Nelson (@deanenelson). What’s especially important to keep in mind is “the difference between just sensationalizing and doing something because it's important,” he says.

“Sometimes, you really have to press forward in an interview to get at something,” Nelson tells Here & Now’s Lisa Mullins. “This is where the discernment comes in.

“Are you getting into some of this deeper, more complicated, maybe more uncomfortable stuff just because it's an audience-getter and a ratings-getter, or are you doing it because it's really important that we develop this?”

Interview Highlights

On how crucial it is to prepare for an interview

“I just was on somebody's podcast just a day or two ago, and I was amazed at how well prepared this guy was. He knew what he wanted to ask, he knew the order he wanted to ask the questions in -— he kind of knew where it was going. So, I would say that kind of preparation makes all the difference in the world.”

On what information you want to get out of the person you’re interviewing

“It's who is this person? Why should we care about this person? And what are we going to talk about that is going to be sufficiently interesting? If you can at least think that one through, you're ahead of a lot of people.”

On the balance between asking questions that are too open-ended and too closed-ended

“I think when you ask open-ended questions, that's always going to elicit a better answer or a better response than a closed-ended [question]. For example, 'Where were you born?' — well, I could say Chicago — as opposed to, 'What was it like growing up in Chicago?' If you're a good interviewer you already know that I was born in Chicago. You've done your homework. Ask it in some way that will draw the person out as opposed to just kind of the one-word answers.

“The danger of the open-ended question is making it so open-ended. I use the example of after some sort of phenomenal Olympic achievement, somebody has just done something that's never been done before and an interviewer will say, 'What does it feel like?' Well, that's so open-ended, it doesn't feel like anything. It's never been done before.

“This goes back to the preparation: If you've actually looked into who some of these athletes are or what they've overcome, I would draw from that. I think a great one that I saw not too long ago was at the end of the Stanley Cup [Championship], the interviewer asked one of the players about having his dad in the rink on the day that the Stanley Cup was won. The interviewer knew that the dad was there. He had some sort of dementia. His dad didn't really know where he was, but his sheer presence in the stands was so important to the player that instead of, 'How does it feel to win the Stanley Cup?,' it was, 'How does it feel to win the Stanley Cup in front of your father, who has come to all these games who took you to early hockey practice when you were a kid?' Now, that really elicited humanity out of that player.”

On how to make sure that as an interviewer, your accuracy and fairness doesn’t get questioned

“If you're recording the interview for instance, you're in pretty good shape. ... There are times that I advise that it's appropriate to type up your notes of what the person said, figure out which quotes you're going to use in your story or in your interview and send those quotes to your source and say, 'I'm not asking for you to correct these. I'm not asking for you to walk it back. I'm just saying this is what I wrote down — did you say it?'

“When somebody says, 'I don't want you to use that quote’ … I just kind of cut a deal with the person, and I said, 'Alright. I will not use this quote under one condition, and that is you give me something better.' … And the person said, 'I'll call you back in a couple hours.' So, he did, and he did give me something better. He so badly didn't want me to use certain quotes, but he was able to make my story so much better, because he gave me something deeper and more thoughtful and frankly more complicated, and that's what made the story better.

"I don't think we were only just now coming to a place where we're not listening to one another. I think egos have always gotten in the way of really relating to one another."

Dean Nelson

On how to ask tough questions

“I'll give you an example. … I asked a question of the author Tracy Kidder, a man I admire a great deal, but he depends a lot on people's memories for his accounts of what he writes about. So, I just asked him, 'How do you know that that's even true? Aren't memories kind of tricky?' And he gave a very thoughtful answer about how much can you actually trust somebody's memory of something that happened 20 years ago, 50 years ago. You could have seen that as a challenge to his accuracy, to his professionalism, but by the time I asked it, he trusted me enough to know that I wasn't attacking him, and then I think he gave a really thoughtful response.”

On the importance of asking deep questions

“I just think there's a way to talk to each other that is healthy and good and that helps us more deeply understand things. And If we did more of that and accepted maybe a little more complexity and a little more nuance, instead of just trying to score points or try to convince our audience of how smart or how superior we are, I think we'd get a little further in how we relate to one another.

“I don't think we were only just now coming to a place where we're not listening to one another. I think egos have always gotten in the way of really relating to one another. But, maybe it's a little more heightened now. So, on the one hand, yeah, I think I'm dealing with a modern social problem. But on the other hand, I think I'm dealing with something that's been with us since we began talking to each other.”

Book Excerpt: 'Talk To Me: How to Ask Better Questions, Get Better Answers, and Interview Anyone Like a Pro'

By Dean Nelson

We Have Questions; We Want Answers

I have learned a lot about interviewing since the Dizzy Gillespie event— first and foremost that interviewing is more common than most of us realize. We ask questions every day because we need to know something, or because we need information so our next decision will be an informed one, or we want to be able to share wisdom, or we want to avoid trouble, or maybe we are just nosy.

Mostly, we are trying to gain perspective on something. If we depend solely on our own thoughts and observations and don’t take into account the thoughts and observations of others who are not just like us, we run the risk of coming to inaccurate conclusions and possibly taking harmful actions. Other perspectives reveal our own biases and assumptions. And think of what could have been accomplished (and avoided!) in our history had we just asked a few more questions. Asking good questions keeps us from living in our own echo chambers.

Think of the questions we have heard or have asked— questions as simple as: “What is the secret to your chocolate chip cookies?” “What happened at school today?” “Did you think about the consequences?” “Would you like to have dinner with me?” “Will you marry me?” “Why is the coffee al-ways gone?” On the one hand, those are simply questions. But they can lead to other questions and become conversations that will draw out personalities and understandings. They can become a kind of interview.

The questions that surround us may be simple and obvious; they may be cosmic and profound. But they all serve a function. Consider the following scenarios from everyday life— in this case mine:

There is a plate of spaghetti on the floor, and the dog is eating it as if he had been waiting his entire life for this moment; his tail is wagging hard enough to spin a turbine. I look at my young son. He is standing, frozen in place, hands outstretched, eyes as big as the plate that is upside down on the floor directly under his hands. I look at my daughter, who is three years younger than my son. She is at the kitchen table, silently crying. Not because of the lost spaghetti or the stained carpet, but because she thinks I am going to punish the dog.

“What happened?” I ask.

That’s an interview question. It’s a dumb interview question (more on asking dumb questions later), because it’s obvious what happened. But it’s an interview question nonetheless. Maybe a better question would be “How did this hap-pen?” And then “What do you think is about to happen?”

Everyone Is an Interviewer

Insurance adjusters, social workers, lawyers, nurses, teachers, investigators, therapists, podcast hosts, customer service representatives, bankers, and police officers spend a good part of each day asking questions. And that’s what an interview is: a purposeful series of questions that leads to understanding, in-sight, and perspective on a given topic. What these people do next depends on the quality of the answers they get. And the quality of those answers has a lot to do with the quality of the questions.

I once had a doctor who never looked up from his computer screen when he asked me questions. I had visits in his exam room for a torn rotator cuff, skin cancer, migraines, and annual physicals. I could barely describe him to you, because all I ever really saw was his hairline over the screen. He asked questions and pounded on those keys like he was trying to smash a scorpion under the keyboard.

In that same clinic I had a doctor who asked me questions other than just what my symptoms were and how often I was going to the bathroom. We talked about our joint love for the lakes in Minnesota, and our joint lament over the quality of journalism in the country. The second doctor’s visits didn’t take much longer than the first. But guess which doctor I was willing to be more open with? Guess who was better able to help me figure out some of my physical issues?

Doctors are under lots of pressure from insurance companies to spend as little time with patients as possible and to document everything. I get it. But even medical journals write that the interviewing skills of doctors can be key to developing adequate diagnoses and therapies for their patients. Good doctors do more than order lots of tests. They ask questions. They listen. They evaluate. They follow up. They interview.

Once I recognized the intentional line of questioning, I appreciated what the second doctor was doing. He wasn’t just getting to know me in a casual sense. It wasn’t like we were going to go out for drinks later. He was gathering information so he could develop a plan. He was, in an informal way, taking my medical history, which is a term doctors use for conducting an interview. It was a conversation, but directed toward a specific goal.

Other careers depend on quality interviews, too. A social worker I know told me that how she works with a client de-pends on what that client tells her. And what that client tells her is a direct result of the questions she asks: “The interview is everything.” Same story for human resources, where the interview is the time you can look past that mountain of near-identical resumes and find out what really sets a candidate apart. Law? A deposition is an interview. Jury selection is a series of interviews. So is a trial, when lawyers ask wit-nesses questions. Financial planners? I have never been asked more personal questions than when I talked to a financial planner. He was interested in my family’s goals, our definitions of success and comfort and security. Those were all interview questions.

Journalists, of course, ask a lot of questions. It’s their job. Most of their careers depend on their ability to conduct a good interview. As a journalist I have interviewed people who were overjoyed, and those who were overwhelmed. Successful, and gutted. Winners and losers. Interesting and dull. Saintly and corrupt. Heroes and antichrists.

Virtually every profession depends on getting people to talk to you, and the good news is that conducting a great inter-view is something you can learn. We see doctors, lawyers, police officers, and journalists on television or in movies, and it seems that they have a poised, professional, confident manner when they conduct interviews. They look like naturals. The shows give the impression that conducting a great interview depends entirely on your being an extrovert with insatiable curiosity. We get a stereotype in our minds about interviewing, that we’re just born with the interviewing gene or we’re not. But I don’t think that’s the case at all. Remember, everyone is an interviewer. Every profession has its times where we need to ask questions of strangers. Boisterous and confident people can be great interviewers. Marc Maron is very good at this. He gives off an air that says, “It’s so cool that you’re talking to me on my podcast, but of course you wanted to talk to me in the first place.” For Maron, it’s a combination of little- kid wonder and arrogance, and it works for him. But shy and insecure people can be great interviewers, too. Some of the best interviewers I have seen are tentative, noncombative, soft- spoken people. Their personalities put people at ease and make them easy to talk to. They know their subject well, and they know that their source can help them gain even more understanding, and they are okay with being vulnerable. I heard the journalist Katherine Boo describe how she got people in Mumbai to be so open with her in her book Behind the Beautiful Forevers. She said that she showed up so often that people sort of forgot that she was there.

Good interviewers are simply themselves. They’re not acting. They’re curious. They know how to be quiet and listen. The authentic ones who ask good questions are the ones who extract profound answers instead of clichés, and who get past the surface and into something that rarely gets explored.

Asking good questions in a good order that leads you to greater understanding will enhance any job, and any life. I have seen it happen with virtually every personality type, in virtually every professional context.

From the book TALK TO ME. Copyright © by Dean Nelson. Published February 19, 2019 by Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by Permission.

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this story for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Jackson Cote adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on March 8, 2019.