Advertisement

Grizzly Bear's Death Illuminates Collision Between Human And Animal Worlds

Resume

One man's job to protect a farmer's corn field from hungry grizzly bears in Montana is the subject of a book that highlights the collision between human and animals.

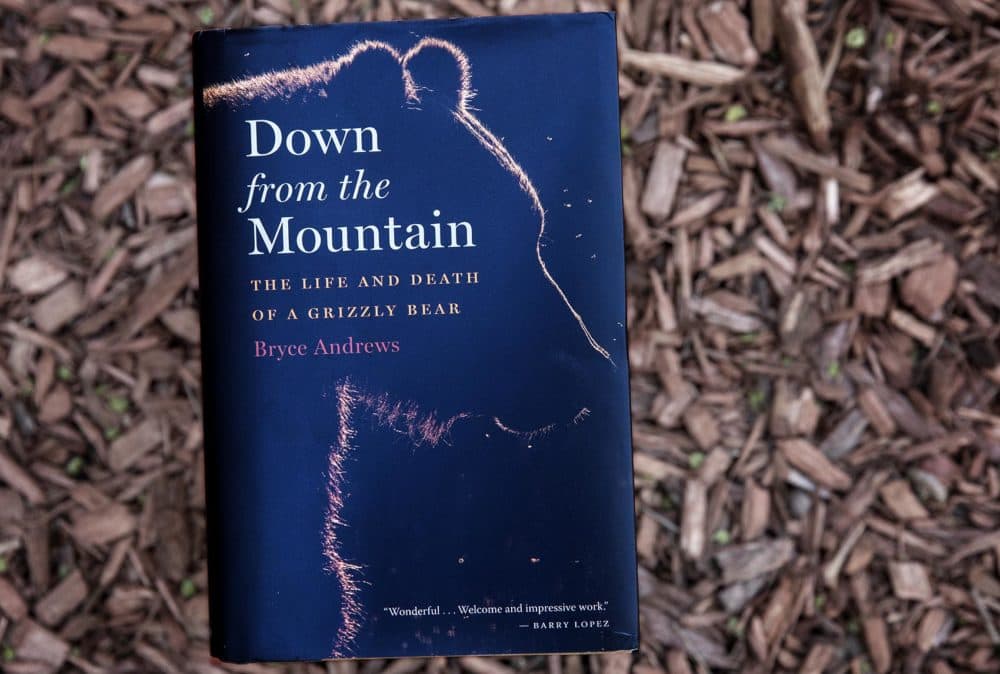

Here & Now's Peter O'Dowd speaks with author Bryce Andrews about "Down from the Mountain: The Life and Death of a Grizzly Bear," about what more humans should do so the two species can live in harmony.

Book Excerpt: 'Down From The Mountain'

by Bryce Andrews

I woke early and restless on Saturday morning, roused my partner, Gillian, and loaded our Subaru with bedrolls, hiking boots and all we’d need for a weekend in the mountains near Glacier National Park. Atop that pile went my voltmeter, an Altoids box full of memory cards and a large, shockproof plastic case containing a brand-new, quad-rotor drone.

I have never been a natural twenty-first century man, and technological advancement comes hard for me. Because of this, I received the news that People and Carnivores, the nonprofit organization I work for, had purchased the drone with mixed feelings. I disliked the thought of harrying the bears, and doubted that I could learn to drive the thing.

Still, the prospect of seeing into the corn captivated me. Prior to the drone’s arrival I had entertained various theories about how best to peer inside the stand. Even the most feasible and reasonable of those notions—rigging a harness to the pivot sprinkler and riding it through a twelve-hour circuit—struck me as the sort of thing that would sit poorly with People and Carnivores’ legal council.

By the time that Gillian and I headed north from Missoula in the car, I was starting to feel more like a technological convert. I watched the land pass with mounting excitement, and soon caught sight of the Missions reaching toward a clear sky. Hands clumsy with nervous energy, I unloaded the plastic case onto the gravel shoulder of Hillside Road, spun four plastic propellers onto drive shafts, and powered up the machine.

The drone took off in a flurry of dust, whining and rising until it was a dot in the blue. I watched the screen of a tablet connected to the controls, looking down at the world through the machine’s camera.

The thing was wonderfully stable, and it hung steady at two hundred feet while I panned the lens downward. The car’s small rectangle came into frame, as did the dots of our heads.

Beyond us, the electric fence was visible as a silver thread, and the field’s dirt apron looked like a tawny beach beside an ocean of growth. Toggling the controls with my thumbs, I sent the drone to sea. It raced off with a yellowjacket’s speed, until I could no longer hear the motors.

I saw the field as never before. From above, the corn was a wide swath of uniform growth, bulls-eyed by wheel ruts. In places, the crop was marred with dark blotches where bears had slept and fed. I descended until I could see cornrows in straight-lined perfection and the crumpled stalks lying in the bigger clearings. Flying lower still, I expected to see a grizzly rise from a daybed and run.

Hoping to see movement, I investigated one trampled spot and then another. Gillian watched the screen with me, inhaling sharply when I flicked the wrong joystick and nearly crashed. Worried that I might lose the contraption on its first day out, I settled for a bird’s-eye view, flying high and trying to get a sense of where and how much the bears were feeding.

What I saw was heartening: Though clearings existed in the corn, they were scattered, small and confined mostly to the field’s northwest corner. They looked like the work of one or a few animals, and the damage fell far short of a twenty percent loss—the figure that Greg Schock, the dairy farmer and ranch owner, had named in seasons past.

Near the middle of the field, in line with the center point of the pivot, bears had been feeding in a straight row. Elsewhere the clearings were scattered, but here they ran straight along a north-south axis. I could not make sense of the pattern until the drone cleared the edge of the field and whined earthward, and I remembered something that Greg had told me when first we talked about the bears.

“They’re smart,” he had said, “even picky. We planted a few acres of sweet corn and they ate that down to nothing before touching anything else. I guess that’s no big deal—you or I would do the same thing. But then I noticed how they ate in the big field. It’s all the same seed out there—all feed corn—but it’s not the same to them. There’s a spot where old property lines come together. The far side used to belong to the neighbors, and the old timers plowed with moldboards, which threw all the dirt to one side. The soil along the old boundary ended up thicker over the years, and the bears know it. They always feed in there, looking for the best, ripest stuff.”

I was impressed that bears could be so picky, and thought about it often as Gillian and I passed the weekend in the mountains. Coming down from a clear, high lake, we found ourselves waist deep in huckleberries. Stopping to gorge on purple-black fruit, we left our packs and foraged the overgrown hillsides. The berries were perfectly ripe, and their endlessness drove us into gleeful frenzy. I stripped fruit from branches with both hands, heedless of all but accumulation.

Staying long in the patch, we filled our stomachs, water bottles, and every other container we’d brought that could be trusted to make the trip home. When we finally left the peaks behind and headed south for Missoula, afternoon was well advanced. By the time we stopped at Schock’s dairy, dusk was building above the Mission Range.

Stepping from the car with bear spray on my hip and the tin of fresh memory cards in hand, I shut off the fence’s current and climbed into the field. The trail camera remained where I had left it, watching over weedy, hard-packed earth. I switched the power off, removed its memory card and put a fresh one in the slot. Walking down the line with one eye on the corn, I repeated the procedure at each of the other cameras. As I slid the final card home, the phone rang in my pocket.

“I see your car,” Greg said. “Come up to the house if you want to see some bears.”

In his ample living room, across from a large, glassed-in fireplace, Greg bent over a spotting scope on a tripod. The scope was positioned to look out the room’s wide windows, across the eastern pastures, toward Millie’s Woods and the mountains.

“Had a milk cow wear out a couple days ago, and since I put her in the dead pit they can’t leave her alone. Got her pretty well cleaned up already,” he said, straightening and making an openhanded gesture toward the scope.

Bending to the reticule, I saw nothing but grass.

“Swing it up,” Greg said. “The pit’s on top of the dike, by the pile of old concrete and pipe.”

While I walked the scope’s field of view up a raw-soiled berm, Greg held forth to Gillian.

“Corn’s coming pretty good this year. This time last summer, it looked rough. Patchy. But then again it was a different kind of year.”

I swiveled the scope toward where a long, low hump of dirt created its own horizon. Seeing movement on the rim, I dialed up the magnification.

“I mean it was dry. This year we’ve had rain. Not a lot, but we’ve had it when we needed it. No late frost, and we’ve had heat when we needed that, too. You look at the apple trees. Look at the fruit, and you can see the kind of year it’s been.”

He went on, but I heard nothing more. Twisting a ring, I brought the scene into focus. In exquisite detail, I saw a cleared space punctuated with bent irrigation pipe and other agricultural debris. At its center, a sow and two cubs worked feverishly at the task of consumption. They bent low over the carcass, and even from a distance I could see how they wrenched flesh from bone.

The sow was an avid feeder. She dropped her muzzle, took hold of some savory bit and yanked with front legs braced, like a dog playing tug-of-war. Sometimes the carcass slid and her cubs stood away, looking to her for a moment before getting back to business. From a distance, with their heads low and their backlines bristled with humped-up fur, the grizzlies brought to mind urchins moving on a seafloor.

Taking turns, Gillian and I watched until the light failed. The sow and cubs kept at their task, and I did not tire of looking. They were still eating when dusk fell. Walking to the car, it seemed good and frightening to be outdoors with them in the gathering dark.

Excerpted from DOWN FROM THE MOUNTAIN copyright © 2019 by Bryce Andrews. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This segment aired on April 29, 2019.