Advertisement

Trevor Noah's Lesson To Young Readers: It's Freeing To Define Yourself On Your Own Terms

Resume

Trevor Noah thinks we should all be young readers.

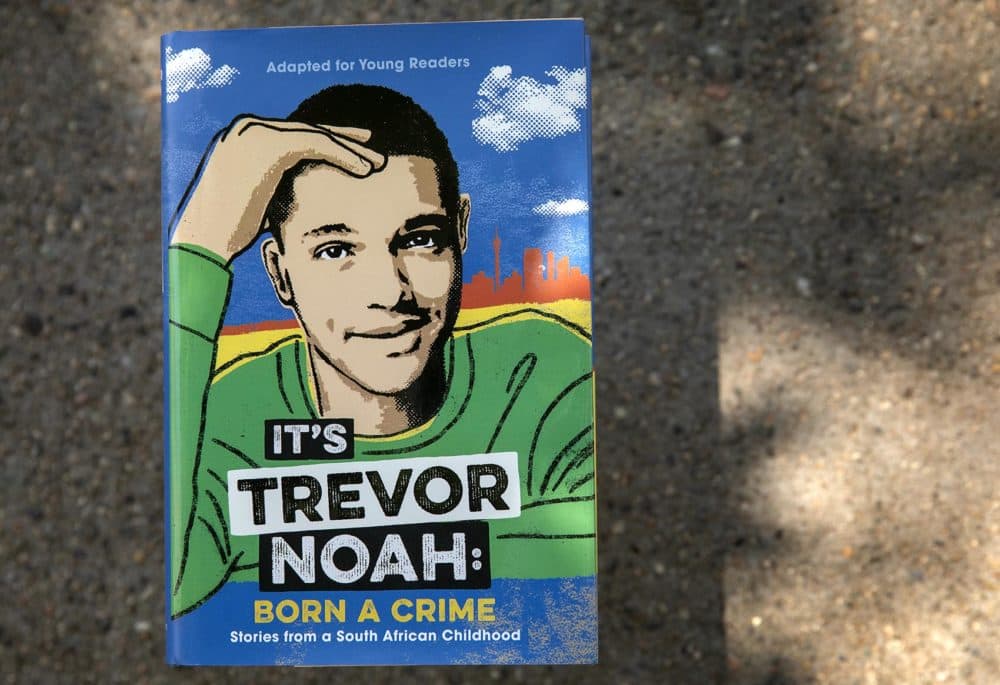

The comedian and "Daily Show" host's new book "It's Trevor Noah: Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood" — a young adult adaptation of his 2016 autobiography — isn't watered down for younger bookworms.

Noah says besides tweaking some of the language and simplifying some of the stories told in the original, his memoir for young adults is largely the same.

"All I changed in the book was just how I described certain concepts, but I didn't try to talk down to younger readers because I didn't like being talked down to when I was young," he tells Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson.

Noah's young adult book aims to provide American kids with an intimate view of what it was like growing up in apartheid South Africa — and to present a deeply personal perspective of how racism shaped the way he saw himself.

He says he hopes American kids reading the book will understand that racism is "an all-too-common idea or a common theme that happens all around the world."

"I think sometimes it's nice to have perspective on these issues, just so that you understand that it's not a unique problem that one country deals with, but rather an idea that society as a whole deals with across borders," Noah says.

His childhood during and after apartheid South Africa shows how as a kid, Noah was grappling with coming to terms with who he was and who he wanted to become. Born to a black South African mother and a white European father, Noah says he felt defined by the government — "it was interesting being in a country where the law defined me as one race" — and by how others labeled him.

Noah says his book serves as a lesson to young readers: There's liberation in defining who you are on your own terms.

"For so long people wanted to define me as whatever they wanted to define me as. I think that clarity for me came from understanding my existence and then looking at the world around me," he says.

Interview Highlights

On why he thinks American kids should know about apartheid

"One thing I enjoyed when I was growing up in South Africa was in our schools, we learned about world history, so we learned about American history. We learned about French history. We learned about what happened in Russia. We learned about Europe. We learned about Africa. We learned about South Africa. And so for me, I think learning about history gives you some context. It gives you an idea of what the world was like. It also gives you an idea of where the world has gone to in comparison to the past. And so for me, if you read stories from South Africa, if you read about apartheid, you come to realize that racism or oppression aren’t unique ideas to America."

On racism in America today

"I think it's unfortunately part of the fabric of the country. South Africa and America have very similar histories in that fundamentally, the beginnings of the countries as we know them, came from a place and a time when people had certain views about people of a different skin color. And so that has traveled through time and that has translated into laws and policies that have affected black people in America [and] black people in South Africa. So for me, what's always interesting is seeing what similarities there are, but then also noticing what differences there are.

"For me, the big difference in the past, you know, we have the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and that's, in many ways, quelled any ideas that [apartheid] never happened or it wasn't as bad as it was laid out to be or was presented as. I think that does something for a nation. It puts you in a place where you can't be gaslighted at anymore, whereas in America, it does feel like this conversation about is there racism, as opposed to how do you begin moving forward as a nation to get rid of the racism that has in many ways defined how people react with one another across racial barriers in the U.S."

On whether racism in the U.S. has gotten worse over time

"I think some people will think it's gotten worse and I'm careful to jump to that assumption. I think we've gotten more access to information and so, you know, sometimes the curves of facts versus information can go against each other. I definitely think America has gotten better over time. For anybody to say that 2019's racism is as bad as 1960's racism, I think it is being a little disingenuous.

"I do think however, social media, camera phones, etc., have given us so much more access to these stories. Now you can watch a video of someone being berated by their boss and their bosses using the N-word in the office. You'd see an unarmed person being shot by a police officer. You would never see that before. It was a story where the police could present the facts however they wished and that would probably be the end of the conversation. So I think we live in a world where now we're getting information on a different scale and processing that information can often mean that even though the world may have gotten better gradually over time, we're now inundated with information that tells us otherwise."

On finding clarity on who he is

"I think as human beings we're always trying to find out who we are. I think sometimes the simplest distinctions to make of those that run along color lines because they fundamentally set you with the group and then you can go from there.

"It was just me understanding where I belonged and who I was, because in South Africa many people were faced with a choice. They could choose to aspire to a racial group that we were told was better than maybe the one we were. I think it was liberating for myself to realize that although the government had tried to define me as one race, I comfortably identified with and was a black person. It seems like an obvious thing maybe, but when you grow up in South Africa, you realize how complicated it could actually be."

On where he is now, personally and professionally, given his upbringing

"I like to think that I am the product of a world of impossibilities. You know, my mother is where she should have never been. I think my mother made greater leaps than I have ever made. It's just that her leaps were made within her world and so maybe don't seem as grand. But I think my family, myself, my country, we come from a place where we have achieved the impossible — a bloodless revolution, a shifting of power from a minority to a majority without there being a mass bloodletting — I think is a really impossible story to tell [and] one that hasn't really been replicated anywhere else. I've come from a world where anything is possible and so for myself, I never ever thought I'd be here because I didn't even know what here is. But I was lucky enough to grow up in a space where I was always told about what was possible. There's a beautiful quote that I read the other day which was, ‘Would you rather know what is real or would you rather know what is possible?’ And I think for me the latter informed how I lived my life."

On his responsibility to inform people through his Comedy Central late-night talk show, "The Daily Show"

"I think I have a responsibility to my audience as much as I have a responsibility to myself. And that's really how I try and create 'The Daily Show' is I try and be as informed as possible as a human being. And then the show would hopefully be a manifestation of that information.

"Also I live in a world where I'm lucky that I'm surrounded by so many individuals who are smarter than myself and so many individuals who push me to think beyond just what I know. When creating 'The Daily Show,' it's that. We're creating, what do we enjoy? We're creating a show that we want to talk about. It's not like in the office we're having conversations that aren't about what's on the air. We talk about politics. We talk about Trump. We talk about what’s in the news. We talk about Brexit. We also talk about pop culture. We're talking about Nicki Minaj and then we'll talk about, you know, boxing fights and the NBA Finals. And for me, 'The Daily Show' should represent that. It should represent a conversation that people are having and hopefully we find an audience that shares all or some of those interests with us.

"And so for me, the obligation I have to my audience is to provide a show to them that I think is interesting, and for me, the news is interesting. Politics is interesting and it also has a lot of fodder to make comedy from. So it's the perfect space for us to be in."

Book Excerpt: 'Born A Crime' (Adapted For Young Readers)

by Trevor Noah

I grew up in South Africa during apartheid, which was awkward because I was raised in a mixed family, with me being the mixed one in the family. My mother, Patricia Nombuyiselo Noah, is black. My father, Robert, is white. Swiss German, to be precise. During apartheid, one of the worst crimes you could commit was having sexual relations with a person of another race. Needless to say, my parents committed that crime.

In any society built on institutionalized racism, race mixing doesn’t merely challenge the system as unjust, it reveals the system as unsustainable and incoherent. Race mixing proves that races can mix— and in a lot of cases, want to mix. Because a mixed person embodies that rebuke to the logic of the system, race mixing becomes a crime worse than treason.

There were mixed kids in South Africa nine months after the first Dutch boats hit the beach in Table Bay. Just like in America, the colonists here had their way with the native women, as colonists so often do. Unlike in America, where anyone with one drop of black blood automatically became black, in South Africa mixed people came to be classified as their own separate group, neither black nor white but what we call “colored.” Colored people, black people, white people, and Indian people were forced to register their race with the government. Based on those classifications, millions of people were uprooted and relocated. Indian areas were segregated from colored areas, which were segregated from black areas—all of them segregated from white areas and separated from one another by buffer zones of empty land. Laws were passed prohibiting sex between Europeans and natives, laws that were later amended to prohibit sex between whites and all nonwhites.

The government went to insane lengths to try to enforce these new laws. The penalty for breaking them was five years in prison. If an interracial couple got caught, God help them. The police would kick down the door, drag the couple out, beat them, and arrest them. At least, that’s what they did to the black person.

If you ask my mother whether she ever considered the ramifications of having a mixed child under apartheid, she will say no. She had a level of fearlessness that you have to possess to take on something like she did. If you stop to consider the ramifications, you’ll never do anything. Still, it was a crazy, reckless thing to do. A million things had to go right for us to slip through the cracks the way we did for as long as we did.

Under apartheid, if you were a black man you worked on a farm or in a factory or in a mine. If you were a black woman, you worked in a factory or as a maid. Those were pretty much your only options. My mother didn’t want to work in a factory. She was a horrible cook and never would have stood for some white lady telling her what to do all day. So, true to her nature, she found an option that was not among the ones presented to her: she took a secretarial course, a typing class. At the time, a black woman learning how to type was like a blind person learning how to drive. It’s an admirable effort, but you’re unlikely to ever be called upon to execute the task. By law, white-collar jobs and skilled-labor jobs were reserved for whites. Black people didn’t work in offices. My mom, however, was a rebel, and, fortunately for her, her rebellion came along at the right moment.

In the early 1980s, the South African government began making minor reforms in an attempt to quell international protest over the atrocities and human rights abuses of apartheid. Among those reforms was the token hiring of black workers in low-level white-collar jobs. Like typists. Through an employment agency my mom got a job as a secretary at ICI, a multinational pharmaceutical company in Braamfontein, a suburb of Johannesburg.

When my mom started working, she still lived with my grandmother in Soweto, the township where the government had relocated my family decades before. But my mother was unhappy at home, and when she was twenty-two she ran away to live in downtown Johannesburg. There was only one problem: it was illegal for black people to live there.

The ultimate goal of apartheid was to make South Africa a white country, with every black person stripped of his or her citizenship and relocated to live in the homelands, the Bantustans, semisovereign black territories that were in reality puppet states of the government in Pretoria. But this so-called white country could not function without black labor to produce its wealth, which meant black people had to be allowed to live near white areas in townships, government-planned ghettos built to house black workers, like Soweto. The township was where you lived, but your status as a laborer was the only thing that permitted you to stay there. If your papers were revoked for any reason, you could be deported back to the homelands.

To leave the township for work in the city, or for any other reason, you had to carry a pass with your ID number; otherwise you could be arrested. There was also a curfew: after a certain hour, blacks had to be back home in the township or risk arrest. My mother didn’t care. She was determined to never go home again. So she stayed in town, hiding and sleeping in public restrooms until she learned the rules of navigating the city from the other black women who had contrived to live there.

Many of these women were Xhosa. They spoke my mother’s language and showed her how to survive. They taught her how to dress up in a pair of maid’s overalls to move around the city without being questioned. They also introduced her to white men who were willing to rent out flats in town. A lot of these men were foreigners, Germans and Portuguese who didn’t care about the law. Thanks to her job my mom had money to pay rent. She met a German fellow through one of her friends, and he agreed to let her a flat in his name. She moved in and bought a bunch of maid’s overalls to wear. She was caught and arrested many times, for not having her ID on the way home from work, for being in a white area after hours. The penalty for violating the pass laws was thirty days in jail or a fine of fifty rand, nearly half her monthly salary. She would scrape together the money, pay the fine, and go right back about her business.

My mom’s secret flat was in a neighborhood called Hillbrow. She lived in number 203. Down the corridor was a tall, brown-haired, brown-eyed Swiss German expat named Robert. He lived in 206. As a former trading colony, South Africa has always had a large expatriate community. People find their way here. Tons of Germans. Lots of Dutch. Hillbrow at the time was the Greenwich Village of South Africa. It was a thriving scene, cosmopolitan and liberal. There were galleries and underground theaters where artists and performers dared to speak up and criticize the government in front of integrated crowds. There were restaurants and nightclubs, a lot of them foreign-owned, that served a mixed clientele, black people who hated the status quo and white people who simply thought it ridiculous. These people would have secret get-togethers, too, usually in someone’s flat or in empty basements that had been converted into clubs. Integration by its nature was a political act, but the get-togethers themselves weren’t political at all. People would meet up and hang out, have parties.

My mom threw herself into that scene. She was always out at some club, some party, dancing, meeting people. She was a regular at the Hillbrow Tower, one of the tallest buildings in Africa at that time. It had a nightclub with a rotating dance floor on the top floor. It was an exhilarating time but still dangerous. Sometimes the restaurants and clubs would get shut down, sometimes not. Sometimes the performers and patrons would get arrested, sometimes not. It was a roll of the dice. My mother never knew whom to trust, who might turn her in to the police. Neighbors would report on one another.

Living alone in the city, not being trusted and not being able to trust, my mother started spending more and more time in the company of someone with whom she felt safe: the tall Swiss man down the corridor in 206. He was forty-six. She was twenty-four. He was quiet and reserved; she was wild and free. She would stop by his flat to chat; they’d go to underground get-togethers, go dancing at the nightclub with the rotating dance floor. Something clicked.

The fact that this man was prevented by law from having a family with my mother was part of the attraction. She wanted a child, not a man stepping in to run her life. For my father’s part, I know that for a long time he kept saying no to fathering a child. Eventually he said yes.

Nine months after that yes, on February 20, 1984, my mother checked into Hillbrow Hospital for a scheduled C-section delivery. Estranged from her family, pregnant by a man she could not be seen with in public, she was alone. The doctors took her up to the delivery room, cut open her belly, and reached in and pulled out a half-white, half-black child who violated any number of laws, statutes, and regulations—I was born a crime.

Excerpt copyright © 2019 by Trevor Noah. Published by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Julia Corcoran produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Kathleen McKenna. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on June 4, 2019.