Advertisement

Remembering The Elaine Massacre In Arkansas 100 Years Later

Resume

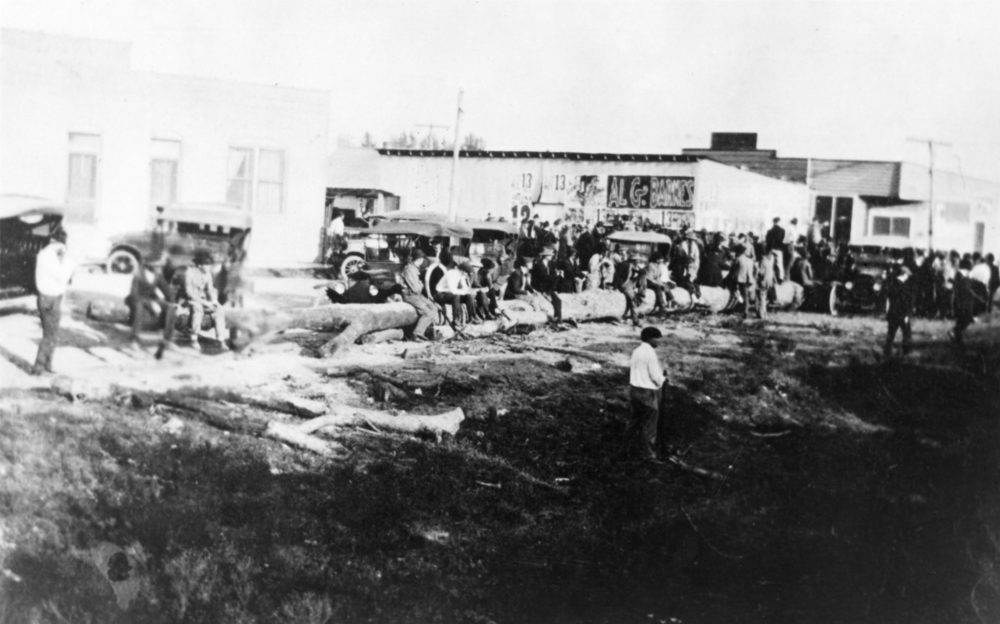

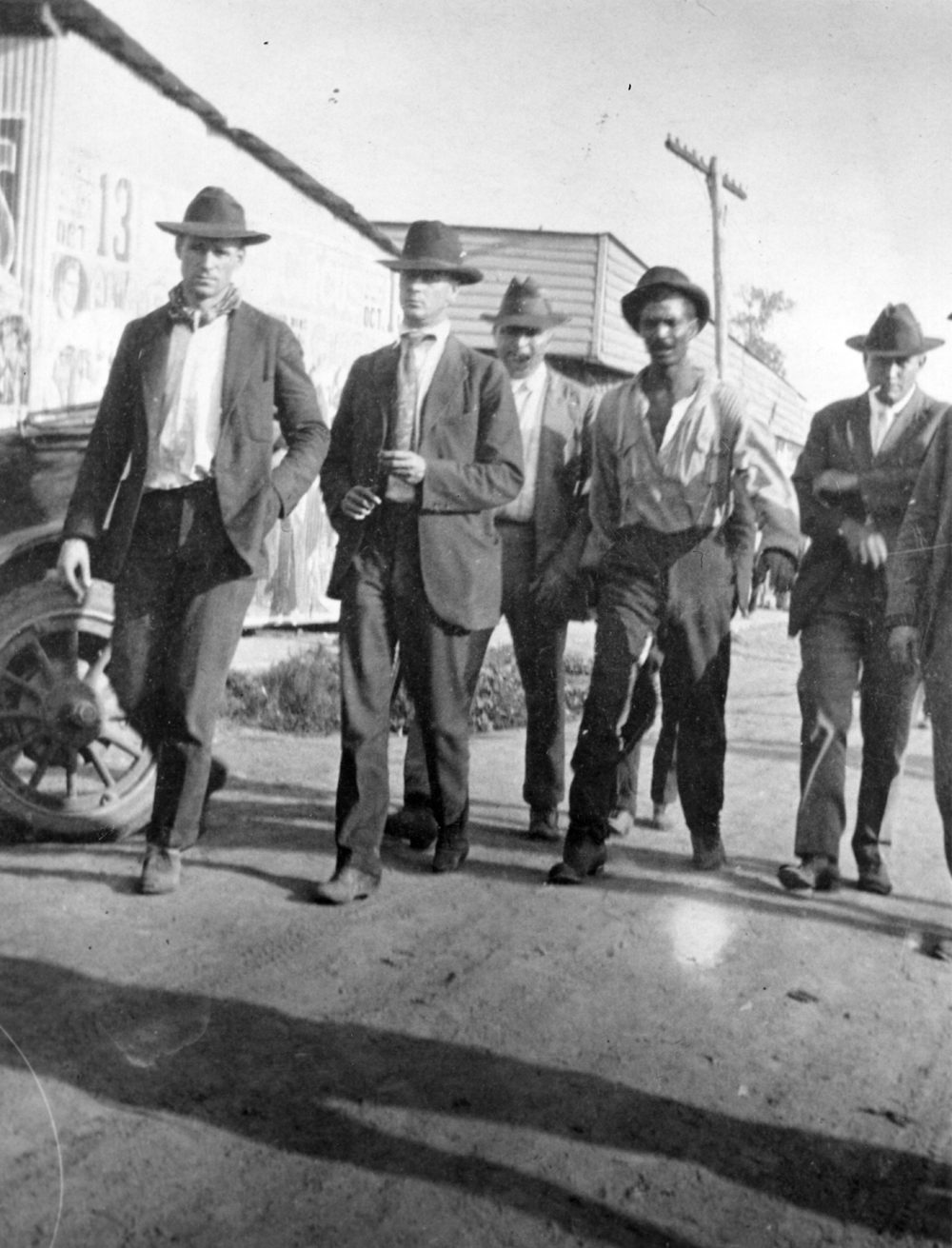

In what’s known as the “Red Summer of 1919,” hundreds of African Americans died at the hands of white mobs, from Chicago to Texas to South Carolina.

In Elaine, Arkansas, white mobs in the Elaine Massacre caused some of the most blood spilled. Death estimates run from 100 to hundreds of murdered black residents, the largest number in the “Red Summer.”

To mark the 100th anniversary, a memorial to the victims is set to be unveiled in Elaine.

Here & Now’s Robin Young talked to Chester Johnson, a white man who co-chairs the Elaine Massacre Memorial Committee and believes his grandfather took part in the massacre.

Johnson says the purpose of the memorial is to “raise an awareness [and] to also lead toward a level of reconciliation coming out of that awareness.”

Memorials and reparations for the victims’ families are “just one piece of the puzzle,” says Kyle Miller, the director of the Delta Cultural Center in Helena, Arkansas.

Miller lost some of his ancestors during the massacre — four young black men who were ripped off a train and killed.

He says the massacre significantly shaped his family, even causing one of his aunts to leave Elaine and never return.

Interview Highlights With Kyle Miller

On when he first found out about the massacre

“My dad would often say ‘the Elaine riots’ and he would make minimal reference to it. I knew it was something significant. I didn't know all the details. And then when I got a little bit older, probably a pre-teen, he then began to share even more and he began his share that we had relatives that had actually died in the massacre but were not actually participating in it.”

On how the massacre impacted his family

“I'm thinking about how even in my family how the results of the massacre, how it shaped us and shaped our family. My grandfather because of the massacre, my family, his mother and father sent him to Boston to a boarding school when he was a young boy. And so he stayed there and then he went to college and then went to medical school. But it's particularly interesting because when he came back, there was almost a detachment. We see now was the part of his personality that even my father never could quite reconcile. And now as I understand the history and the events of the massacre, I understand how he shaped to be that because him being a young boy not really quite understanding everything that was going on and then being sent out from his family. It created a detachment that had a ripple effect on our family for years to come.”

On the economic impact of the killings

“One of the brothers there in Helena had an automotive dealership and the other was a dentist. So you have a dentistry business, he also had a drugstore as well. That was totally disintegrated because of the incident along with the car dealership. D.A. Johnson, who was the dentist, who was married to my great aunt after the massacre, she moved away and she never came back to Phillips County. Never.”

On reparations

“I think that there are some valid discussions and arguments to be made. This is one piece. I think that's how we have to look at it. It is one piece of the puzzle and building upon a foundation hopefully even greater things to come.”

On if there’s anyone alive in his family who knew his slain ancestors

“No. However I will say this. My great aunt, who was married to D.A. Johnson who was one of the brothers who was murdered, after the massacre she moved to Chicago. And like I said she never came back and it was only until this past year at a family reunion that side of the family ever came to Helena to Phillips County. And that was the first time they had ever been to Phillips County in almost 100 years. And so that was a whole population of our family that we've now connected to as a result of moving towards the monument and they'll be there in September.”

Interview Highlights With Chester Johnson

On when he first learned about the massacre

“It was much later that I learned about the Elaine race massacre. In 2008, I wrote the Litany for offense and apology when the Episcopal Church, the national Episcopal church, formally apologized for its role in transatlantic slavery and related evils. And as I was doing a lot of my research, I came across this book that had been written by Ida Bell Wells-Barnett called the Arkansas race riot. And in that there was a reference to Phillips County and this terrible event with so many African Americans perishing. And I grew up one county removed from Phillips County and I grew up knowing nothing about this. And I began to do research into it and I realized that a story that my own mother had told me about my grandfather, my maternal grandfather, coalesced with what I was reading and Ida Bell Wells-Barnett.”

On when he found out someone in his family took part in the massacre

“Well even beyond that, my father died when I was one [years old] and I lived with my maternal grandparents for the first few years of my life because my mother didn't do very well. My caretaker was Lonnie Birch and we were very close. I mean, he took care of me 24 hours a day. And then later I find that that he had participated in this terrible event. And initially, when you're confronted with that, you realize that maybe I can somehow reconcile the wonderful person that I knew, who cared for me so deeply, with this person who participated in the massacre. And over time, I realized I couldn't do that, that he would forever remain two separate people.”

On feeling personal guilt from the actions of his family members

“Really, it's a complicated issue. I believe in something that's called damaged heritage, not necessarily guilt, but that we inherit a history that we did not make but yet we are partied to it, and that undoubtedly plays a role in the way I look at this at this moment in history.”

On the memorial, and people’s rejections to it

“Well I was actually surprised by the number of white people who indicated that they would prefer that this memorial not go up and they had general issues within terms of is this going to raise ill feelings, particularly among African Americans. But I agree with Kyle on this. The purpose of this memorial is different than the issue of reparations.”

Mark Navin produced this interview and edited it for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Serena McMahon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on September 12, 2019.