Advertisement

Bringing The Pulitzer Prize-Winning '1619 Project' To A Wider Audience

Resume

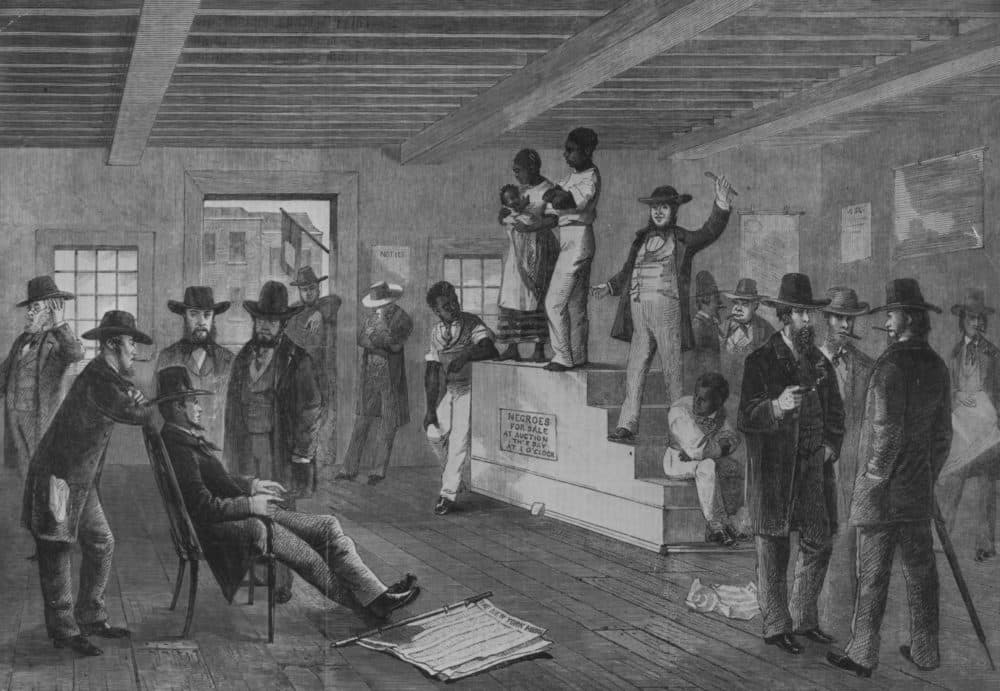

“The 1619 Project” from The New York Times refers to the year that the first enslaved people were brought to the U.S. and looks at how slavery continues to shape every aspect of American culture.

When it was first published last August, the magazine created a sensation, and this past May, “The 1619 Project” won a Pulitzer Prize. Now, Oprah Winfrey and Lionsgate have teamed up with creator Nikole Hannah-Jones to bring the work to an even wider audience through multiple platforms.

“The 1619 Project” continues to resonate during ongoing Black Lives Matter protests because it contributes to the lexicon of how America reached this current period of racial reckoning, Hannah-Jones says.

“I think it has allowed many Americans, particularly white Americans, to connect dots that they weren't connecting before,” she says, “that this police violence and inequality, that these aren't just unrelated incidents, but have a long and deep legacy that has to be confronted.”

The project is also inspiring changes to school history curriculums in Chicago, Washington, D.C. and Buffalo, New York. This marks the latest push for more accuracy in American history textbooks, which have been under scrutiny for being “highly politicized” and embodying a “nationalistic agenda,” Hannah-Jones says.

Teaching a history “that speaks to American exceptionalism” downplays the role of slavery, she says, and “all of the other ways that America has not lived up to those ideals of exceptionalism.”

“That has robbed Americans of the ability to properly assess their country and why things are like they are,” she says.

What many parents have recognized is that “The 1619 Project” offers a counter to that narrative, which Hannah-Jones hopes will prompt people to question other narratives in U.S. history.

“There are many different stories that really need to be told so that we can have a fuller version of the American project,” she says, “and not just one that seeks to glorify us, but really one that seeks to challenge us.”

Interview Highlights

On if this period of racial reckoning will lead to reparations

“I don't think that there is enough of an appetite for it right now. I just was looking at some polling on this yesterday and it showed among white Democrats — so, you know, the party that the vast majority of Black Americans vote for — that only about 30% of white Democrats support the idea of reparations. So clearly, there is a lot of work to do on that. But at the same time, I think, again, it's related to the work of ‘The 1619 Project.’ There is such a visceral response that many of white Americans have to the idea of reparations, and I think that's really based on the fact that they actually have no understanding of this history. They have no understanding of the singularity of Black suffering, of the dragnet of laws and policies that have created the generational disadvantage that Black Americans face. And part of what I try to do with my piece on ‘What Is Owed’ is really lay that history out and really show that there is nothing that Black Americans can do on our own to erase a 350-year system of racial segregation and economic exploitation.

“So no, we're not ready for that yet. But part of the work that I'm doing and that so many others are doing is trying to move that conversation forward so that we can maybe get to the point where we can be serious about addressing that. And we have seen movement. So when you look at the fact that in … the Democratic primary debates, reparations was treated as a serious question by journalists and by people on that stage. Five years ago, you wouldn't have seen that. When you look at H.R.40, which is the bill to study the issue of reparations, it's been introduced every year for 30 years and has never made it out of committee. But a few years ago, it had just three co-sponsors. Now it has well over 100 co-sponsors. So we are seeing some traction, and like many things, when it comes to racial justice, it's a decades long struggle, not a months, a years-long struggle.”

On the racial reckoning also happening in newsrooms

“Yeah, I think there is a reckoning happening right now. And of course, when you are a Black journalist, you've never bought into this idea that your identity is unrelated to your coverage. And we've known that that's not true for ourselves, and we've certainly known that that's not true for white journalists either. Of course, white journalists' identity in a white-dominated society plays a role in how they cover stories, what they choose to cover and what they don't.

“So it's always been interesting to me that our role as journalists is to explain the world to itself. And so here we are reporting on these national reckonings — a racial reckoning is happening across all of these different institutions and all of these different organizations and private companies — yet we don't fully understand this ourselves, and we have not dealt with these issues ourselves. So how can we explain to the world that which we don't fully understand? So I think this is a very interesting time that we're in where Black journalists are speaking out and are really pushing our news organizations in a public way, which is more unusual. And I hope that the only reckoning that comes out of this time of protests, that it also comes to our industry as well. If we see ourselves as really the linchpin, the free press as a lynchpin of democracy, then we have to democratize our own institutions.”

On if she is optimistic that this moment will lead to change

“No. No, I'm not. I think I'm realistic, and realistically, if you study history, then you know that massive transformation is very rare and only comes after very sustained periods of resistance, and then it never fully transforms society and is often faced by a backlash and a retrenchment. So I'm already looking at how little news coverage the protests are getting, how little coverage we're seeing in media around if there's actually going to be police reforms or not. We're already seeing this narrative because of a rise in shootings that, you know, we can't defund police because look at all this violence in these communities. So I think that what we're fighting against is so deeply entrenched that it's hard to be hopeful that we're going to see that real necessary transformation. With that said, I am hopeful that people will keep fighting, because even if we don't think that we're going to see that, we are, I think, obligated to fight for it.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on July 20, 2020.