Advertisement

Meet One Farmer Who Left His Tech Job To Transform Northern Virginia's Agroscape

Resume

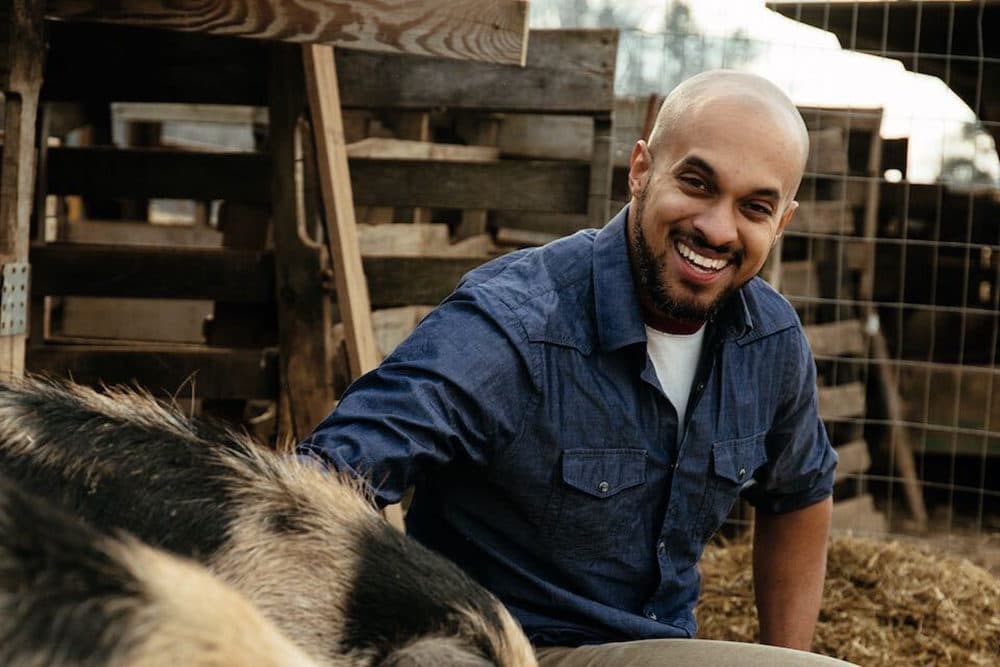

Chris Newman quit his job in tech to start Sylvanaqua Farms outside of Washington, DC. — near where his Piscataway ancestors once managed acres of corn and fish along the Potomac River.

Sylvanaqua Farms is focusing on pasture-raised chickens and eggs, forested pigs and grass-fed beef, he says. The farm is also starting to preserve rare seeds of Indigenous varieties of corn, beans and squash.

The “rapidly growing,” “diversified” farm plans to create a complete food production landscape by also reincorporating wilding and foraging into agriculture, he says.

“We mostly consider ourselves land protectors and water protectors first who happen to grow food,” he says.

Newman decided to quit his job as a software engineer because of the stress and health issues that came with it. A nonexistent work-life balance and sleeping in the office led his wife to encourage him to pursue agriculture.

The farm’s practices come from Newman’s ancestors — knowledge you can’t learn in a book. His mother is Black and his father belongs to the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, but he says for both of them, “it was like the arc of progress absolutely went away from the farm.”

His maternal grandfather was a successful farmer in the Virginia Tidewater region who grew peanuts and corn, and raised hogs. But he dealt with discrimination on the farm, Newman says.

White farmers would harvest his fields last so they could charge drying fees, and people set fire to tractors that belonged to neighbors who would help him, Newman says.

In contrast, his dad didn’t have an agricultural background because of a Native concept similar to an Uncle Tom, called a “Hang Around the Fort Indian.” Used among Native Americans to describe people who pandered to the U.S. military during the Reservation Era, the term now represents a stigma that exists among Native people in the Western U.S. around settling down on one piece of land, he says.

Many communities view farming on one piece of land as a form of surrendering traditional ways of life: hunting game, foraging and managing large landscapes, he says.

For Newman, he regards the soil as the blood and bones of his ancestors — who gifted him the nourishing food that grows.

“There was kind of a lot of cultural baggage to get over when we decided we wanted to come back to the land and try to make a living on it as an expression of independence, as honoring the ancestors who came before my grandparents,” he says.

While some food sovereignty advocates believe that large farms are bad, Newman says a middle ground exists between a global agriculture system and “Mr. and Mrs. Smith's 15 acres.” Indigenous people sustainably managed large foodscapes before making contact with Europeans.

In firsthand accounts, people like John Smith or Henry Fleet described an “Edenic paradise” created by God, he says. But they didn’t understand that the area was a large-scale food forest cultivated by Indigenous people.

“They didn't realize what they were standing in,” he says. “They didn't realize that they were basically on a farm. It didn't look like anything they would think of as a food-producing landscape.”

The farm-to-table movement has been driven by entrepreneurs with access to money and land, he says. But large farms can leverage economies of scale and have more ownership.

This is why Newman believes in collectivism over a relationship between farm owners and workers. Large farms can make more of a difference with ecological restoration, too, he says.

“If you're operating on, say, 7,000 or 8,000 acres as opposed to 100, you can actually restore a watershed,” he says. “You can restore ecosystems at a scale that matters when you're operating at that size.”

As far as messaging that encourages people to avoid eating GMOs or buy organic, Newman says telling people what they should eat is a “settler, colonial mindset.”

In the U.S., a toxic culture exists around food where consumers want to buy things that solve a particular problem, he says. Consumer movements such as veganism put too much responsibility on people who are desperate because of inequality caused by “slowly eroding democratic norms in the United States,” he says.

These consumer solutions offer an “illusion of control” that aims to substitute deeper societal problems, he says. Farming is part of the solution, but people need to continue the deeper work that’s happening now in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd and nationwide protests.

“I think that awakening is happening,” he says. “As sad and as sometimes hopeless as things seem to be now, there are glimmers of hope that I think are more encouraging than anything I've seen in my lifetime.”

Cassady Rosenblum produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Peter O'Dowd. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on August 10, 2020.