Advertisement

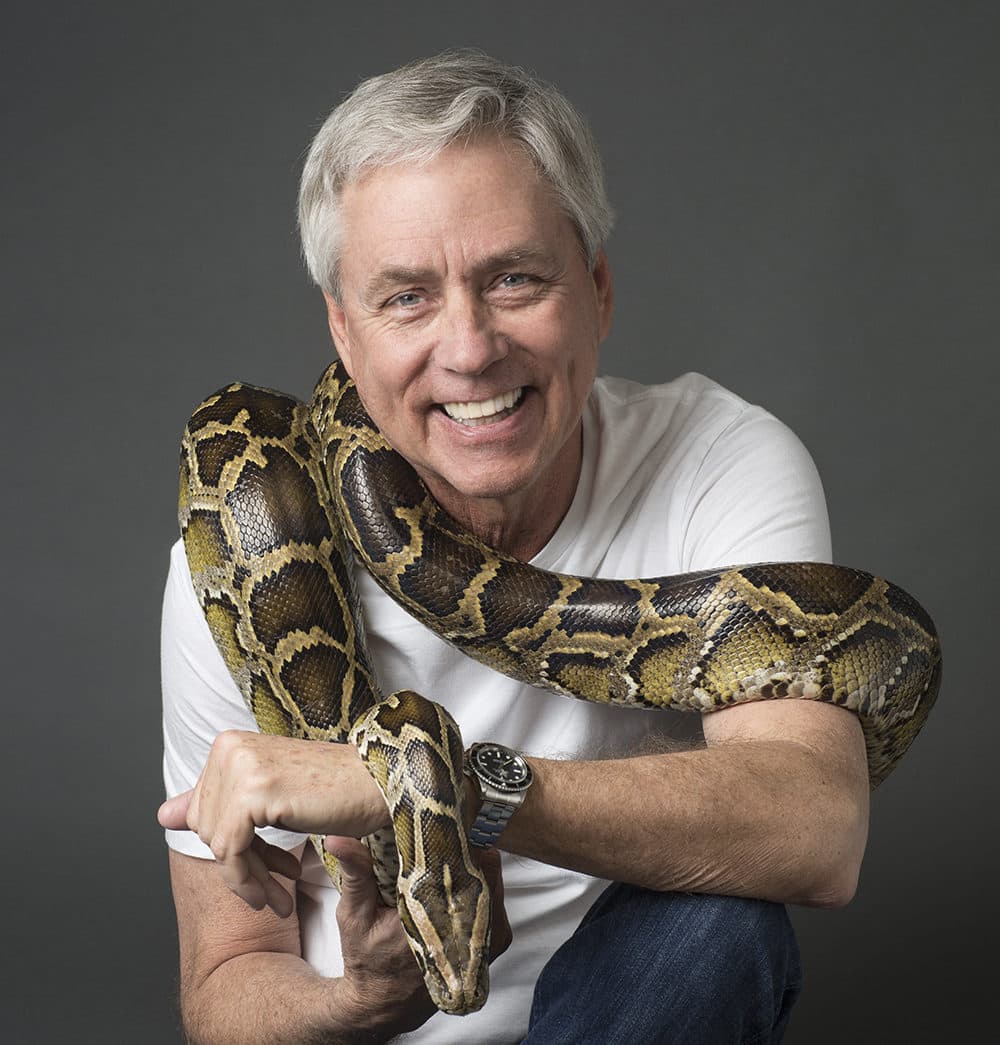

Pythons And POTUS Populate New Carl Hiaasen Novel, 'Squeeze Me'

Resume

Pythons, an animal wrangler and a missing socialite who is a devoted fan of a reality TV star-turned president are just some of the zany characters in Carl Hiaasen’s new novel, “Squeeze Me.”

The author and Miami Herald columnist’s latest book follows in his traditional satirical skewering of the absurd in the state he loves — Florida. Hiaasen’s humor barely conceals his disdain for those who destroy Florida’s natural beauty with over-development or just plain stupidity.

In “Squeeze Me,” Hiaasen writes about the wealthy Palm Beach crowd, including a former reality TV celebrity-turned commander in chief — inspired by President Trump — with a Velcroed hair piece, which a screech owl confuses for a roadkill fox.

The novel puts the reader right in the middle of Palm Beach charity ball season when a high-profile socialite mysteriously goes missing at a fundraising gala for irritable bowel syndrome. Could one of those giant snakes found in the Everglades be the culprit?

As Janet Maslin says in her rave review of the novel in The New York Times, “Look at yourself: If you are wearing a MAGA anything, you won’t like this book.”

While he was writing “Squeeze Me,” Hiaasen says he feared that something he cooked up in his head would actually happen. Sometimes his fears came true.

“In the times we live in, it's very tough to do satire. Humor is difficult because you think up a scene or a character or a plotline that you think is so far out there,” he says. “And then you pick up the newspaper the next day or you go online and you see that there's a guy in the White House who's suggesting it's a great idea to inject Clorox into your veins to cure COVID-19.”

Much of the story takes place at a resort inspired by the real-life Mar-a-Lago, where Hiaasen actually met Trump about a decade ago. He says he also drew inspiration from the Palm Beach Daily News’ “Shiny Sheet,” a section of the newspaper highlighting the goings-on in the glitzy beach town’s high society.

“I've observed some of it, but you let your imagination run wild,” he says. “Then your job as a novelist is just to take the ball and run with it, and the bad part was pretty easy.”

Interview Highlights

On the history of Burmese pythons in Florida

“Well, they're big and they're prolific, and they haven't found a way to stop them. There's thousands and thousands of them out there and they grow to about 18-feet-long and they can eat an adult alligator. And they've migrated out of the Everglades. They've sort of eaten their way through the food chain and they move north. And, you know, I don't know that they've reached the island of Palm Beach yet, but I kind of wrote the novel for all of us who couldn't be there when it happened.

“To my knowledge, nobody's been eaten yet by one of these big pythons. … However, they've eaten, full grown white-tailed deer, for example. So it's not a big leap. It was kind of an irresistible combination. You think about, I mean, honestly, in my twisted mind, pythons, Mar-a-Lago, and then the book sort of writes itself.”

On what this book says about Florida

“It's not just a setting. It's not just a locale. I mean, this is the kind of place that's a character itself in every book. I mean, it is that significant a landscape. And it's so diverse and it's so beautiful and it's so frustrating and exasperating to live here because it's changing continually and filling up with people. I think we now, you know, there's over 20 million people. And so that clash of this kind of wild and beautiful place with people coming from everywhere and filling it up is bound to be rich material for a writer.

“Now, it's not an accident that a lot of the most popular writers in the country have come here, including Stephen King, John Grisham ... Karen Russell, who's caught it in a way not very many people have. I mean, it's just extraordinary. But it brings that out. If you're a writer and you land here and I mean, if you come straight from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop or somewhere and they plop you down in Florida, you're gonna be busy. There's no end to the material. And in a way, like I, born and raised here, and you love the place and you find it also maddening, the writing itself becomes a form of psychotherapy.”

On his depiction of some of the local women in Palm Beach

“Well, I think that's probably a description that applies far beyond Palm Beach County. But when you're writing lines, you know, when you're actually writing, at least for me — Dave Barry and I have talked about this, too — you're not smiling or even laughing at what you're writing. There's part of you that says, 'Oh, that's funny,' or 'That works,' or that the timing is good or that adjective is perfect. But there's a part of you that says, 'Is it right? Is the rhythm of it right? Does it look good on the page? Is it funny?' But it's a grim work when you're doing it. And when you're finished and you see that it works and you get such great reactions from people who are laughing at it, then it just validates your instinct. But when you're doing it, it can be grinding because one wrong word and that sentence isn't funny anymore.”

On the woman at the center of the novel, Angie, the wildlife wrangler

“She's the hero of the book. … I mean, a lot of [my] novels have women who are the lead role or a protagonist in them. And I just find them, they tend to be more interesting. They're stronger. They're smarter than the rest of the cast of characters usually, which in my own experience is true in real life. You never know when you start. Originally that character when I was writing it was a male character because most of the people in that business, wildlife removal business in Florida — you call them and they come get the raccoon out of your attic or something — most of those folks are men. And so that's where I'd started. But I was, I don't know, 50 or 75 pages in and I thought, 'God, I think this would be much more fun if she was a woman in that profession, and she'd have to deal with a little bit more and a little bit of, you know, skepticism and a little bit of doubt.' And so I just liked her from the beginning. I really lucked out.”

On his brother, Rob Hiaasen, who was killed in The Capital Gazette shooting and to whom the book is dedicated

“I knew I would [dedicate the book to him]. I don't know that it changed the way I wrote. I think what happened was I went through a period after Rob was killed, and he just was, let me just say, an incredible writer himself. And he was funny and wise and smart and just sharp and had this wonderful sense of humor. And I was frozen really for a couple of months. I mean, the first thing I went back to do, and it took me two months after he was killed to do it, was to start my column again because I just knew he would've wanted me to keep writing. And then, I mean, it wasn't easy. It was the first time in my whole life that I just couldn't.

“And then once I started the column, I started thinking about the novel and gradually worked up to where I could launch on it because it's what he would have wanted me to do. The last thing he would have wanted me to do was sort of bail out and quit. And also, I kept thinking of his sense of humor the whole time while I was writing ‘Squeeze Me’ because I know he would have enjoyed it. You know, we always talked about books, and I think he was a motivation, honestly Robin, to keep going because it was you know, there were some dark times and it's hard to be funny some days when things happen like that. It's hard to be ... sit down and write humor for someone else and for readers who are expecting. My readers are just terrifically loyal and they're also sharp. And if I was off my game at all, I would have felt like I couldn't do the book. So it took a while, but I think in the end it helped me.”

Emiko Tamagawa produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Samantha Raphelson adapted it for the web.

Book Excerpt: 'Squeeze Me'

By Carl Hiaasen

On the night of January twenty-third, unseasonably calm and warm, a woman named Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons went missing during a charity gala in the exclusive island town of Palm Beach, Florida.

Kiki Pew was seventy-two years old and, like most of her friends, twice widowed and wealthy beyond a need for calculation. With a check for fifty thousand dollars she had purchased a Diamond Patrons table at the annual White Ibis Ball. The event was the marquee fundraiser for the Gold Coast chapter of the IBS Wellness Foundation, a group globally committed to defeating Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Mrs. Fitzsimmons had no personal experience with intestinal mayhem but she loved a good party. A fixture on the winter social circuit, she stood barely five feet tall and weighed eighty-eight pounds sopping wet. Her gowns were designed on Worth Avenue, her hair-and-makeup was done on Ocean Boulevard, and her show diamonds were cut on West 47th Street in Manhattan.

Kiki Pew’s guests at the White Ibis Ball were three other widows, a pallid set of roommate bachelors and one married couple, the McMarmots, whose clingy devotion after four decades of marriage was almost unbearable to observe. Kiki Pew spent little time at her table; a zealous mingler, she was also susceptible to Restless Legs Syndrome, another third-tier affliction with its own well-attended charity ball.

The last person to interact with Mrs. Fitzsimmons before she vanished was a Haitian bartender named Robenson, who under her hawk-eyed supervision had prepared a Tito’s martini with the requisite orange zest and trio of olives speared longitudinally. It was not Kiki Pew’s first cocktail of the evening. With cupped hands she ferried it from the high-domed ballroom into sprawling backyard gardens filled with avian-themed topiary—egrets, herons, raptors, cranes, wood storks and of course the eponymous ibis, its curly-beaked shadow elongated on the soft lawn by faux gaslight lanterns.

Inside the mansion, the other guests gathered for the raffle, which, for a grand prize, offered a private cruise to Cozumel that would inevitably be re-gifted to the winner’s college-age grandchildren in time for spring break. Alone with her vodka, Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons wended through the maze of bird shrubbery toward a spleen-shaped pond stocked with bright gold fish and bulbous koi. It was upon that silken bank where Kiki Pew’s beaded clutch would later be discovered along with her martini glass and a broken rose-colored tab of Ecstasy.

The venue for the event was known as Lipid House, which in addition to its Mizner-era ballroom featured two dining halls, a cavernous upgraded kitchen, a library, a piano room, a fitness center, twenty-five bedrooms, nineteen-and-a-half baths, an indoor archery range, and Waterford hand-sanitizer dispensers in every hallway. Among Kiki Pew’s retinue only the McMarmots were sober enough to organize a search, assisted somewhat perfunctorily by members of the service staff. It wasn’t uncommon to find a missing party guest snoring on a toilet.

The door-to-door hunt for Mrs. Fitzsimmons interrupted an unsightly entwinement in a north-wing bedroom—the chromium-haired heiresses of two separate liquor fortunes, tag-teaming a dazed young polo star from Barcelona. Wordlessly the searchers turned away and moved on. There was no trace of Kiki Pew in the building.

The McMarmots proposed interviewing the bartender, but he was already gone. Robenson always endeavored to get off the island before midnight, unless he could hitch a ride with a white friend. Driving alone, Robenson had been pulled over so many times that he now paper-clipped his employment documents to the sun visor of his Taurus, for easy retrieval when quizzed by the Palm Beach cops.

The Fitzsimmons search party moved outdoors and boarded golf carts to scour the walled ten-acre estate. Because the area around the koi pond was faintly lit, no one spotted Kiki Pew’s purse on the bank. After a fruitless hour spent calling her name, the McMarmots extended a theory that she must have drunk too much, forgot about her waiting driver from the car service, walked the quarter-mile home, and passed out. Kiki Pew’s other companions embraced this scenario, for it also would explain why she wasn’t answering her phone.

Nobody noticed the authorities until the next morning, after Kiki Pew’s housekeeper found her bed untouched, the cats unfed. Meanwhile, at Lipid House, the supervisor of the grounds crew was instructing his workers to mow carefully around the small purse, martini glass and the tiny broken pill on the grass.

The chief caretaker of the estate met the police at the gate and escorted them to the scene. It appeared to the officers that Mrs. Fitzsimmons had consumed half the tablet and either decided to have a swim, or accidentally toppled into the pond.

“Can you drag it ASAP?” the caretaker said. “We’ve got another event tonight.”

The officers explained that the body of water was too small and inaccessible for a full-on dragging operation, which required motorboats. Shore divers were summoned instead. Groping through the brown muck and fish waste, they recovered numerous algae-covered champagne bottles, the rusty keys to a 1967 Coupe de Ville, and a single size-5 Louis Vuitton cross-pump, which the McMarmots somberly identified as the property of their missing friend.

Yet the corpse of Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons wasn’t found, which perplexed the police due to the confined location. The sergeant on scene asked Mauricio, the supervisor of the Lipid House groundskeepers, to continue watching the pond for a floater.

“Okay. Then what?” Mauricio said with a frown.

Katherine Sparling Pew began wintering in Palm Beach as a teenager. She was the eldest granddaughter of Dallas Austin Pew, of the aerosol Pews, who owned a four-acre spread on the island’s north end.

It was there, at a sun-drenched party benefiting squamous-cell research, that Katherine met her first husband. His name was Huff Cornbright, of the antifreeze and real-estate Cornbrights, and he proposed on their third date. They were married on Gibson Beach at Sagaponack, Long Island, where the Pew family convened every summer with tenuously managed rancor. The New York Times chronicled the Cornbright-Pew wedding with six colorless paragraphs and a scrapbook-worthy photograph of the joyful couple. Katherine used the occasion to unveil her chipper new nickname, a custom among post-debutante women of a certain upbringing.

Huff and Kiki Pew Cornbright settled in Westchester County, producing two trendily promiscuous offspring who made decent grades and therefore needed only six-figure donations from their parents to secure admission to their desired Ivies. The family was jolted when, at age fifty-three, Huff Cornbright perished on an autumn steelhead trip to British Columbia. Swept downstream while wading the Dean River, he foolishly clung to his twelve hundred-dollar fly rod rather than reach for a low-hanging branch and haul himself to safety.

Kiki Pew unloaded the Westchester house but kept the places she and Huff had renovated in Cape Cod and Palm Beach. His ample life-insurance policy paid off both mortgages, which had outlived their usefulness as tax deductions. Meanwhile, the Cornbrights’ now-grown sons had found suitable East Coast spouses to help liquefy their trust funds, freeing Kiki Pew to spread her wings without feeling the constant eye of filial judgment. She waited nearly one full year before seducing her Romanian tennis instructor, two years before officially dating eligible men her age, and four years to re-marry.

The man she chose was Mott Fitzsimmons, of the asbestos and textile Fitzsimmonses. A decade earlier he’d lost his first wife to an embolism while parasailing at Grand Cayman. Among prowling Palm Beach widows Mott was viewed as a prime catch because he was childless, which meant less holiday drama and no generational drain on his fortune.

He was lanky, silver-haired, seasonally Catholic and steeply neo-conservative. It was Kiki Pew’s commiserative coddling that got him through the Obama years, though at times she feared that her excitable spouse might physically succumb from the day-to-day stress of having a black man in the Oval Office. What ultimately killed Mott Fitzsimmons was nonpartisan liver cancer, brought on by a stupendous lifetime intake of malt scotch.

Kiki Pew was consoled by the fact that her husband lived long enough to relish the election of a new president who was reliably white, old and scornful of social reforms. After Mott’s death, with his croaky tirades still ringing in her bejeweled ears, Kiki Pew decided to join the POTUS Pussies, a group of Palm Beach women who proclaimed brassy loyalty to the new, crude-spoken commander-in-chief. For media purposes they had to tone down their name or risk being snubbed by the island’s PG-rated social sheet, so in public they referred to themselves as the Potussies. Often, they were invited to dine at Casa Bellicosa, the Winter White House, while the President was in residence. He always made a point of waving from the buffet line or pastry table. During the pandemic lockdown, he even Zoom-bombed the women during one of their cocktail-hour teleconferences.

News of Kiki Pew’s disappearance at the IBS gala swept through the Potussies faster than a blast sales alert from Saks. The group’s cofounder—Fay Alex Riptoad, of the compost and iron ore Riptoads— immediately dialed the private cell phone of the police chief, Jerry Crosby, who assured her that no resources would be spared in the effort to solve the case.

“We’ve already issued a Missing Persons bulletin to the media,” the chief said. “I asked the state to do a Silver Alert, but—”

“Anybody can get a Silver Alert, even on the mainland,” Fay Alex sniffed. “Isn’t there a premium version for people like us? A Platinum Alert, something like that?”

“Silver is the highest priority, Mrs. Riptoad. However, it’s only for seniors who go missing in vehicles.” Crosby had learned the hard way never to use the term “elderly” when speaking with the Palm Beach citizenry. “Since Mrs. Fitzsimmons wasn’t driving the other night, the best they can do is a Missing Persons bulletin.”

Fay Alex said, “You didn’t give out her real age to the media, did you? There’s no call for that. And which picture of her did you post?”

“We’re required to list the age provided by her family. One of her sons sent us a photo from a family gathering on Christmas Day.”

“A morning picture? Oh, dear God.” Fay Alex groaned; noon was the absolute earliest that Kiki Pew allowed herself to be seen by civilians.

When the police chief inquired if Mrs. Fitzsimmons was known to use psychoactive drugs, Fay

Alex threatened to have him sacked. “How can you even ask such a vicious question?” she cried.

“A pill was found among your friend’s belongings, next to the fish pond. Actually, part of a pill.

Our expert says it was bitten in half.”

“For heaven’s sake, Kiki was on blood-pressure meds. Who isn’t! She kept hers in a cute little Altoids tin.”

The chief said, “The fragment we found wasn’t high-blood pressure medicine. It was MDMA.”

“What in the world are you talking about?”

“On the street they call it Ecstasy, Mrs. Riptoad.”

“Ecstasy!” she yipped. “That’s the most ludicrous thing I’ve ever heard. Kiki Pew, of all the girls, wouldn’t have a clue where to get something like that.”

In fact, Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons knew exactly where to get something like that—from her tennis pro, with whom she had resumed bi-weekly lessons soon after Mott passed away. Kiki enjoyed the MDMA high, which lasted for hours and kept her energized even after too many drinks. She had come to believe that the pill gave her a strategic edge at posh island functions, where most attendees began to fade and ramble by nine-thirty, ten at the latest.

“One bad side effect of the drug,” Jerry Crosby explained to Fay Alex Riptoad, “is a sensation of overheating. Users tend to feel hot and sweaty even when it’s chilly outdoors. That might explain why Mrs. Fitzsimmons went into the water—to cool off.”

“Then where’s the body? I seriously doubt the koi ate her.”

“The pond is very murky. It’s possible our divers couldn’t see her under the surface. We’ll know for sure in a day or two, when . . . well, we’ll know.”

“Kiki Pew is not a druggie,” Fay Alex re-asserted, “and I won’t listen to another word of this insulting rubbish. Here’s a radical idea, Jerry: Just do your fucking job. Find her!”

That evening, the Potussies gamely dressed up and gathered at Casa Bellicosa. They left an empty chair where Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons usually sat, and ordered a round of Tito’s martinis in her honor. Other club members stopped by the table to express support and seek updates.

“Oh, I’ll bet our little Keek is just fine,” one man said to Fay Alex. “She probably got confused and wandered off somewhere. My dear Ellie does that from time to time.”

“Your dear Ellie has Stage 5 dementia. Kiki Pew does not.”

“The onset can be subtle.”

Fay Alex said, “Let’s all stay positive, shall we?”

“But I am,” the man replied, canting an eyebrow. “Being mixed-up and lost is positively better than being dead at the bottom of a fish pond, no?”

During the yard crew’s lunch break, Mauricio noticed that one of the large standing mowers had been abandoned, its throaty motor idling, on the Lipid House croquet lawn.

“Where the hell is Jesús?” Mauricio shouted to the others. “He knows he can’t leave the Hoosker there!”

Hoosker was the crew’s nickname for the big Husqvarna stand-on, twenty kick-ass horses and the sweetest turning radius in the trade.

“Jesús he gone,” said one of the men.

“What do you mean gone? He just quit and walked off?”

“Not walk. He run.”

“What the fuck,” Mauricio said. “Which way did he go?”

The man pointed.

Mauricio stared. “What are you saying—he climbed the damn wall?”

“He just jump from Hoosker and haul ass,” the man said. “I don’t know why, boss.”

Mauricio walked over to the tall stucco wall and examined the fresh scrapes in the ivy showing the path of Jesús’s hasty ascent.

“Crazy fool,” Mauricio muttered. Then to the others he yelled: “Move that hot mower and get a hose on those treadmarks! Ahora!”

Ten miles away on the mainland, in a neighborhood of modest duplexes, Jesús’s wife knew something was wrong the moment he walked in the door.

“What is it?” she asked.

“They’re going to fire me, Gloria.” He told her everything, the words spilling out.

“Dios mío!” she cried. “What did Mauricio say?”

“I spoke to no one.”

“But you’ve got to go back and warn them!”

“I can’t do that, Gloria. You know why.”

“The police are there? I don’t understand.”

Jesús shrugged dismally. “They are searching for that missing woman.”

Gloria fell silent. Her husband was undocumented. He could be in serious trouble if police detectives started interviewing the yard workers at Lipid House. Maybe they’d ask to see a visa, maybe they wouldn’t.

These were perilous times. Jesús’s young brother, Esteban, was currently in government custody awaiting deportation. The week after Christmas, he’d been detained during the pre-dawn raid of a 7-Eleven in Wellington, handcuffed by armed ICE agents while he was repairing the Slurpee machine.

Gloria fixed a ham-and-pork sandwich for Jesús. She asked if there was a chance to save his job.

“No way,” he answered morosely. “I left my mower with the engine running.”

“In gear?”

“God, no! In neutral.”

“So then, that’s good. There’s no damage done,” his wife said.

“But it was parked on that bentgrass lawn where they do the croquet.”

“What is croquet, Jesús?”

“Where they chase the colored balls around with hammers. The grass is soft and muy caro.”

“Oh, no!”

“I was scared,” he said. “So I just jumped off the machine and—”

“But you’re sure about what you saw?”

“Yes, Gloria. It’s something I will never forget.”

“Es horrible.”

“Why do you think I ran?”

Jesús pushed his sandwich away after two bites. His wife made the sign of the cross as she whispered a prayer.

Somebody knocked at the door. “Are you there, Jesús? Open up!”

It was Mauricio. Gloria let him in and went to the bedroom, leaving the two men alone.

Jesús said, “I’m sorry, boss.”

“The catalytic converter on the Hoosker, it burned a damn patch on the croquet field.”

“You can take it out of my last day’s pay.”

Mauricio shook his head. “No, I told Teabull it was a mechanical problem.”

Tripp Teabull was the chief caretaker of Lipid House, and he understood nothing about the exhaust systems of stand-on mowers.

“Did he believe you?” Jesús asked.

“Por supuesto. They’re already re-sodding the lawn.”

“Thank you, boss.”

“Tell me what happened, and maybe you still have a job.”

Jesús said, “It doesn’t matter. I can’t ever return to that place.”

Mauricio, who was aware of the plight of Jesús’s brother, promised to deal guardedly with the police. He said, “There’s no reason to give out your name.”

“It’s not only that, boss. I can’t go back there again because of what I saw.”

“I need to know.”

“You’ll say I’m crazy.”

“I’m the head groundskeeper. Or did you already forget?”

“If I tell you . . .” Jesús looked up at the wooden crucifix on the wall. Then his chin dropped.

“Was it the missing woman you saw?” Mauricio asked.

Jesús shuddered and said, “Sort of.”

Excerpted from Squeeze Me by Carl Hiaasen. Copyright © 2020 by Carl Hiaasen. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

This segment aired on September 3, 2020.